It was W. G. Sebold who said that animals and men gaze at each other across a gulf of mutual incomprehension. Here is a film that crouches on the screen like a great sullen beast. It is impossible to embrace, impossible to dismiss. I do not know what it is thinking, how it perceives life. But the film is not about animals. It is about men and women, inarticulate to the point of silence, putting one weary foot ahead of another in a march toward sadness.

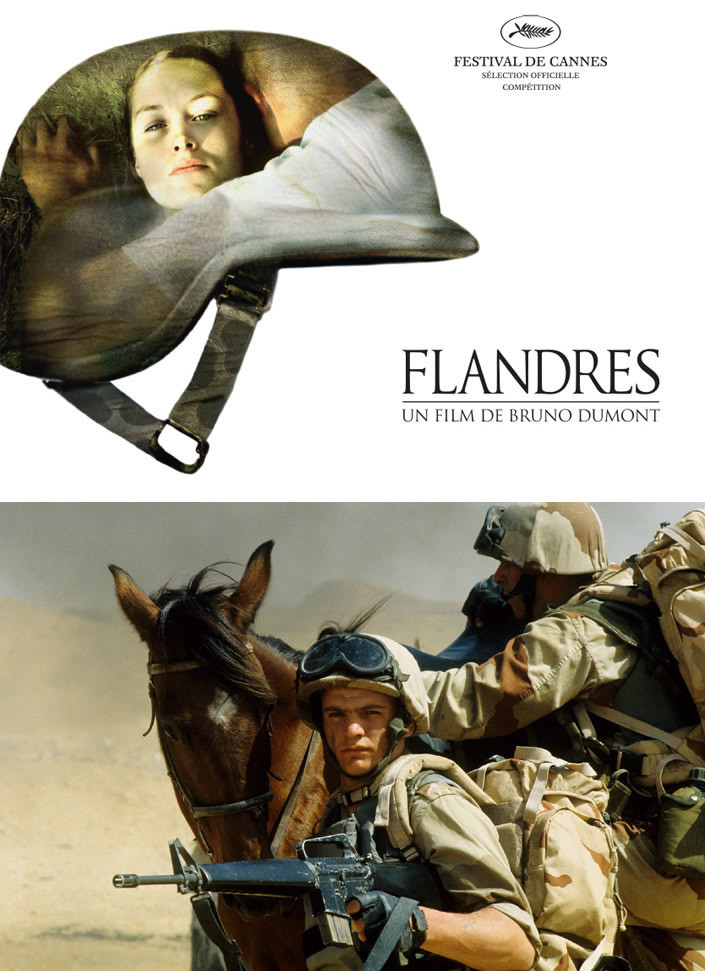

“Flanders,” by Bruno Dumont, won the Jury Prize at Cannes 2006. His “L'Humanite” won the same prize in 1999. Both films require a special kind of viewer. I wrote of “L’Humanite” that it is “for those few moviegoers who approach a serious movie almost in the attitude of prayer.” But we do not approach “Flanders” as if attending a religious service. We are its pastor, helpless to console it. It stands wet and lonely outside our church of the human race.

The movie takes place in a pale cold season, February or March, in that rural area of Belgium that saw some of the most brutal fighting of World War I. It occurs in the present day, when the tractor’s plow turns up with the earth some white chalky stuff that might once have been bones. It is primarily about Barbe (Adelaide Leroux), a thin, unsmiling girl; Demester (Samuel Boidin), a passive farm worker, and Blondel (Henri Cretel), also a farm worker, so limited that he accepts Demester’s blank silence as companionship.

Demester leans on a fence, staring at the fields. Barbe comes to stand next to him. “Did you get your letter?” she asks. He did, calling him to war. “You go on Monday?” He nods. “Shall we?” He nods. They walk across the fields, bed down in a hedgerow and have sex with the efficiency of hedgehogs. It is not as good for her as it is for him, because, we do not need to be told, it has never been good for either of them.

A group gathers in a rural tavern. They do not even get drunk. They drink their beer dutifully. Demester refuses to agree that he and Barbe are “a couple.” She leaves the table and picks up Blondel. That will show him. But Demester does not much react, Blondel does not seem to have won anything, Barbe does not seem to think she has made much of a point.

Demester, Blondel and other locals are trucked away to be sent to an unnamed war in an unnamed land. They commit atrocities, are themselves the victims of unspeakably horrible experiences. Demester, who survives, returns. Barbe in the meantime has had an abortion, spent time in a mental hospital, is back on the farm. They have sex again. “I love you,” Demester says. They are the saddest words in the movie.

This film has few tangible pleasures, such as some somber shots of Demester walking far away in a field. Its achievement is theoretical. It wants to depict lives that are without curiosity, introspection and hope. I watched with mournful restlessness. I admire it more today than yesterday when I saw it. I will never “like” it. I can imagine showing it to a film class and confronting the uncertain eyes of the students: What forlorn “masterpiece” had I forced upon them? How would I defend it?

I would say Dumont takes them about as far as they will ever want to go in the direction of human emptiness. Or maybe his film takes them nowhere, but simply occupies a place. It is “Waiting for Godot” without dialogue or the expectation of Godot. It is Bressonian, but demonstrates how Bresson is sublime and Dumont is implacably stolid. Consider Dumont’s character of Barbe and then, if you have the chance, watch Bresson’s miraculous “Mouchette.” You want to console Mouchette. You want to regard Barbe from across a room, wondering how her personality displaces so little karma.

The actors are all locals, unprofessional, but fully equal to Dumont’s barren designs for them. I recall when Emmanuel Schotte, the star of Dumont’s much more involving “L’Humanite,” won the best actor award at Cannes, and all of my friends agreed that in his acceptance speech the actor seemed exactly the same as his character. Is that acting? Perhaps it is one goal of acting.

Gene Siskel sometimes said a film was not as interesting as a documentary of the same actors having lunch. I would be interested in seeing Adelaide Leroux and Samuel Boidin having lunch together, or even having sex together. It is unutterably depressing to reflect they might seem the same as here. If this is life, then death I think is no parenthesis.

Note: I give the film three stars, because I don’t want to discourage anyone who finds this description intriguing. On my Web site is a place for readers to vote. Consult their ratings carefully. My reviews of “L’Humanite” and “Mouchette” are online.