Bruno Dumont‘s “L’Humanite” has the outer form of a police movie, but much more inside. It is not about a murder, but about the policeman in charge of the investigation. It asks us to empathize with the man’s deepest feelings. I saw this film a week after “Shaft.” Both films are about cops driven to the edge of madness by a brutal crime. “Shaft” is about the story, “L’Humanite” is about the character.

“L’Humanite” is not an easy film and is for those few moviegoers who approach a serious movie almost in the attitude of prayer. A great film, like a real prayer, is about the relationship of a man to his hopes and fate.

The man this time is named Pharaon De Winter. He is played by Emmanuel Schotte as a man so seized up with sadness and dismay that his face is a mask, animated by two hopeless eyes. He lives on a dull street in a bleak French town. Nothing much happens. He once had a woman and a child, and lost them. We know nothing else about them. He lives with his mother, who treats him like a boy. Domino (Severine Caneele) lives next door. She has an intense physical relationship with her lover Joseph that gives her no soul satisfaction. It is impossible to guess if Joseph even knows what that is.

There is a scene where Pharaon walks in as they are making love, and regards them silently. Their lovemaking is not erotic or tender, but just a matter of plumbing arrangements. Domino sees him standing in the doorway. Later she asks him, “Get an eyeful?” He mumbles a lame excuse. She says something hurtful and leaves. Then she returns, touches him lightly and says, “I’m sorry.” When she leaves again, he pumps his fists in the air with joy.

Why? Because he loves her or wants her? It isn’t that simple. He is like those children or animals who go mad from lack of touching and affection. His sadness as he watched them was not because he wanted sex, but because they were getting nothing out of it. His joy was because she touched him, and indicated that she knew how he felt, and that she had hurt him.

He is a policeman, but he has no confidence or authority. The opening shots show him running in horror from a brutal murder scene, and falling inarticulate on the cold mud. He tells his chief how upset he is by the crime. He doesn’t have the chops to be a cop. He watches a giant truck race dangerously through the narrow lanes of the town, and then exchanges a sad shrug with the old lady across the street. His police car is right there, but he doesn’t give chase.

His relationship with Domino and Joseph is agonizing. He goes along with them on their dates for sad reasons: He has nothing else to do, they have nothing to talk about with each other, he’s no trouble. Because Joseph is the dominant personality, he enjoys flaunting the law in front of Pharaon, who is so cowed he can’t or won’t stop him. There’s a scene with the three of them in a car, Joseph speeding and running stop signs, and Pharaon impotently saying that he shouldn’t. Domino listens, neutral. And a scene where Joseph behaves piggishly to bystanders, and Pharaon is passive. The dynamic is: Joseph struts, so that Domino can observe that he is more of a man than Pharaon the cop. Pharaon implodes with self-loathing.

The murder investigation continues, sending Pharaon to England and to an insane asylum. His efforts are not really crucial to the solution of the case. In a way, the rape and death of the girl at the beginning is connected with his feelings for Domino–because she offers him sex (in a friendly way) and he cannot separate her body from the memory of the victim in the field. The rapist has taken away Pharaon’s ability to see women in a holy light.

The movie is long and seemingly slow. The actors’ faces can be maddening. We wait for something to happen and then realize that something is happening– this is happening. In the spiritual desert of a dead town, murder causes this cop to question the purpose of his life. Eventually he goes a little mad (notice the way he sniffs at a suspect).

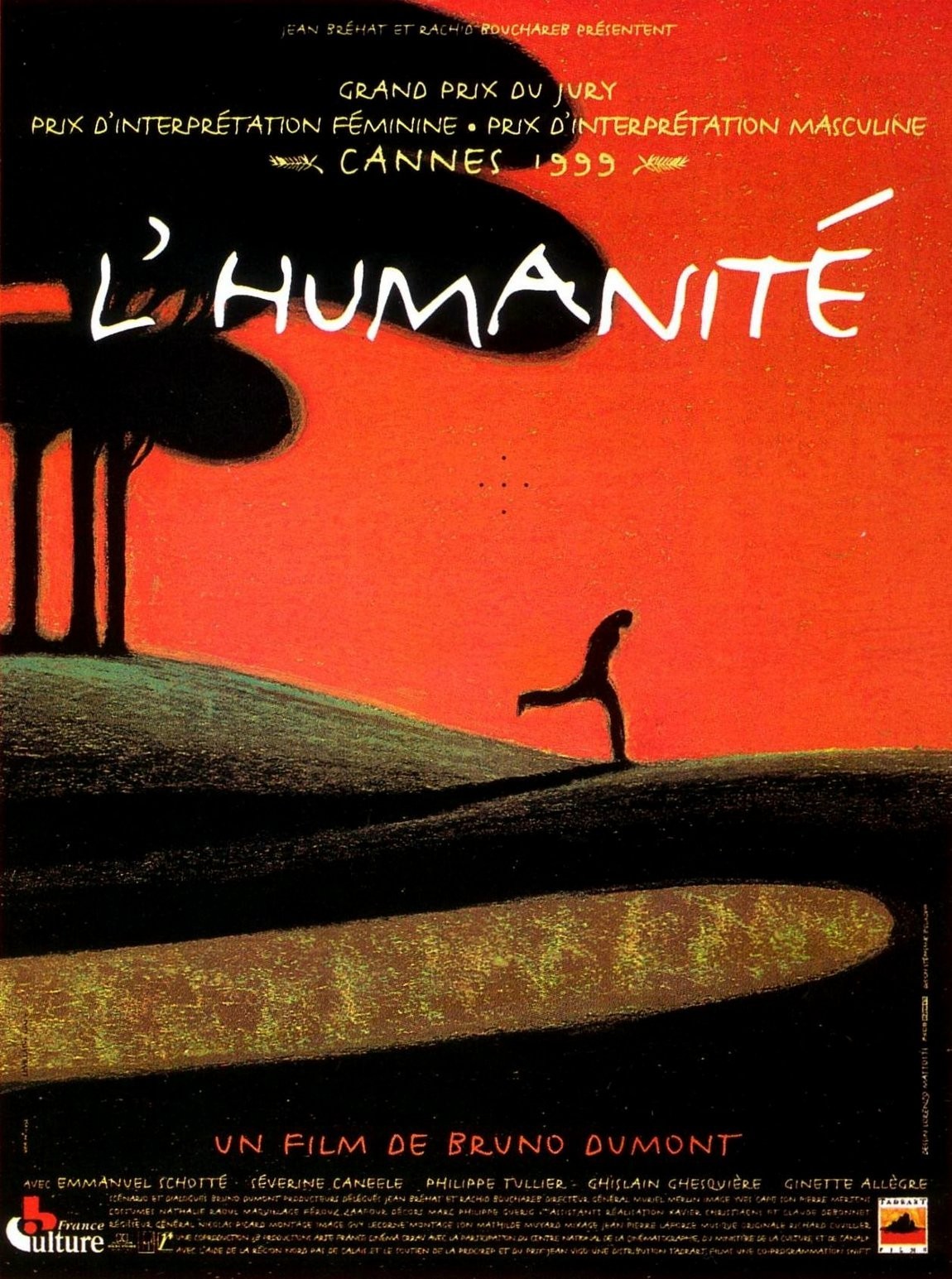

The film won the grand jury prize at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival; Emmanuel Schotte won as best actor, and Severine Caneele shared the best actress award. Onstage, Schotte seemed as closed-off as in the film. Perhaps Bruno Dumont cast him the way Robert Bresson sometimes cast actors–as figures who did not need to “act” because they embodied what he wanted to communicate.

The Cannes awards were not popular. Well, the movie is not “popular.” It is also not entirely successful, perhaps because Dumont tried for more than he could achieve, but I was moved to see how much he was trying. This is a film about a man whose life gives him no source of joy, and denies him the consolation of ignorance. He misses, and he knows he misses. He has the willingness of a saint, but not the gift. He would take the suffering of the world on his shoulders, but he is not man enough. The film is not perfect but the character outlives it, and you will not easily forget him.