Werner Herzog makes documentaries that are designed more to illuminate what we don’t know than detail what we do. Films like “Encounters at the End of the World” and “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” are in awe of the natural world more than trying to explain it. So it makes sense that the best parts of his latest, “Fireball: Visitors from Darker Worlds,” co-directed with Clive Oppenheimer (his collaborator on “Into the Inferno”), are segments that feel more philosophical than scientific. Herzog’s film comes to life when it’s in awe of the concepts he’s exploring here, including the idea that a meteorite that lands, due to how far it’s traveled through space, is instantly the oldest thing on the planet. He structures “Fireball” around how these rocks that have hurtled past planets have impacted humanity, including cultures that have sprouted up around and even in craters. The result is a film that can be a bit dry when Oppenheimer leads the scientific discussion but that springs back to life when Herzog the filmmaker allows his awe to come through the camera.

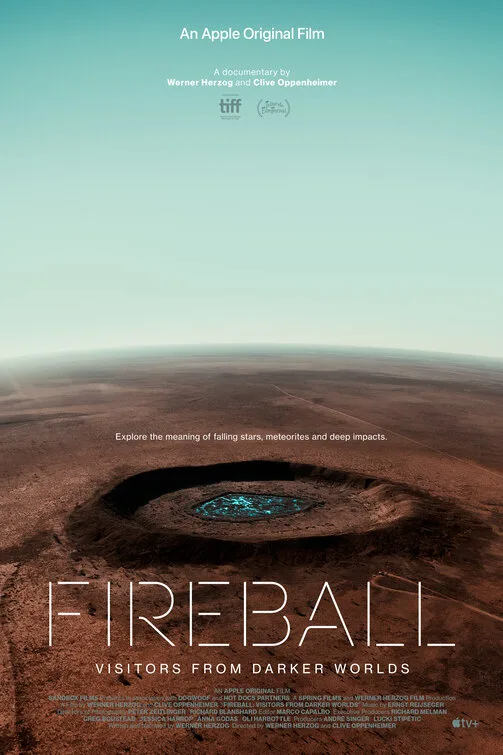

“You don’t want to do science if you don’t have a sense of awe and wonder.” Spoken by a religious man who studies meteors, this could be the operating theme behind most of Herzog’s nature documentaries over the last two decades. He brings that awe and wonder to various locations across the planet, joined by co-director Clive Oppenheimer, who is often on-camera, interviewing experts on the subject of meteorites. He often lets his camera linger over samples of meteor, or puts it on a drone to capture impacts on the planet that can’t really be seen when one is on the ground. The film alternates these very Herzogian visuals and narrative segments with more scholarly conversations with Oppenheimer and the people on our planet who know the most about these fireball visitors.

“Fireball” is really a collection of scientific and cultural vignettes. In the centerpiece, the pair gets to the Yucatan Peninsula, where it’s believed the meteor to end all meteors crashed and ended the reign of the dinosaurs. Oppenheimer gleefully explains the impact of the legendary meteor—earthquakes, tsunamis, ash that blankets the sky—while Herzog’s camera carries the film through the streets of what both men call a “Godforsaken” part of the planet. However, their analysis begins with the meteor crash instead of ending there. They draw the line between the crash to the water holes it created inland, where the Mayan culture sprouted up. The Mayans saw these holes as passageways to the underworld and built their society around them. “Fireball” is at its best when it’s drawing a line from astronomy to religion to philosophy.

It falters during some conversations between Oppenheimer and experts that even Herzog’s glee can’t quite inject with life. While the night watchmen who keep an eye on the skies to make sure there’s nothing large enough to impact the planet headed our way may be interesting, you can almost sense Herzog wanting to get back outside and spend more time with the people who worship the meteors than the ones who endeavor to explain them or stop them. For Herzog, nature is something to be honored and awed by as much and maybe even more than understand. He has long interrogated man’s relationship to the natural world in both his fiction and non-fiction filmmaking. This time, he’s connecting that passion to natural occurrences that emanate from beyond the stars, but his joyous fascination remains the same.

Premieres on Apple TV+ today.