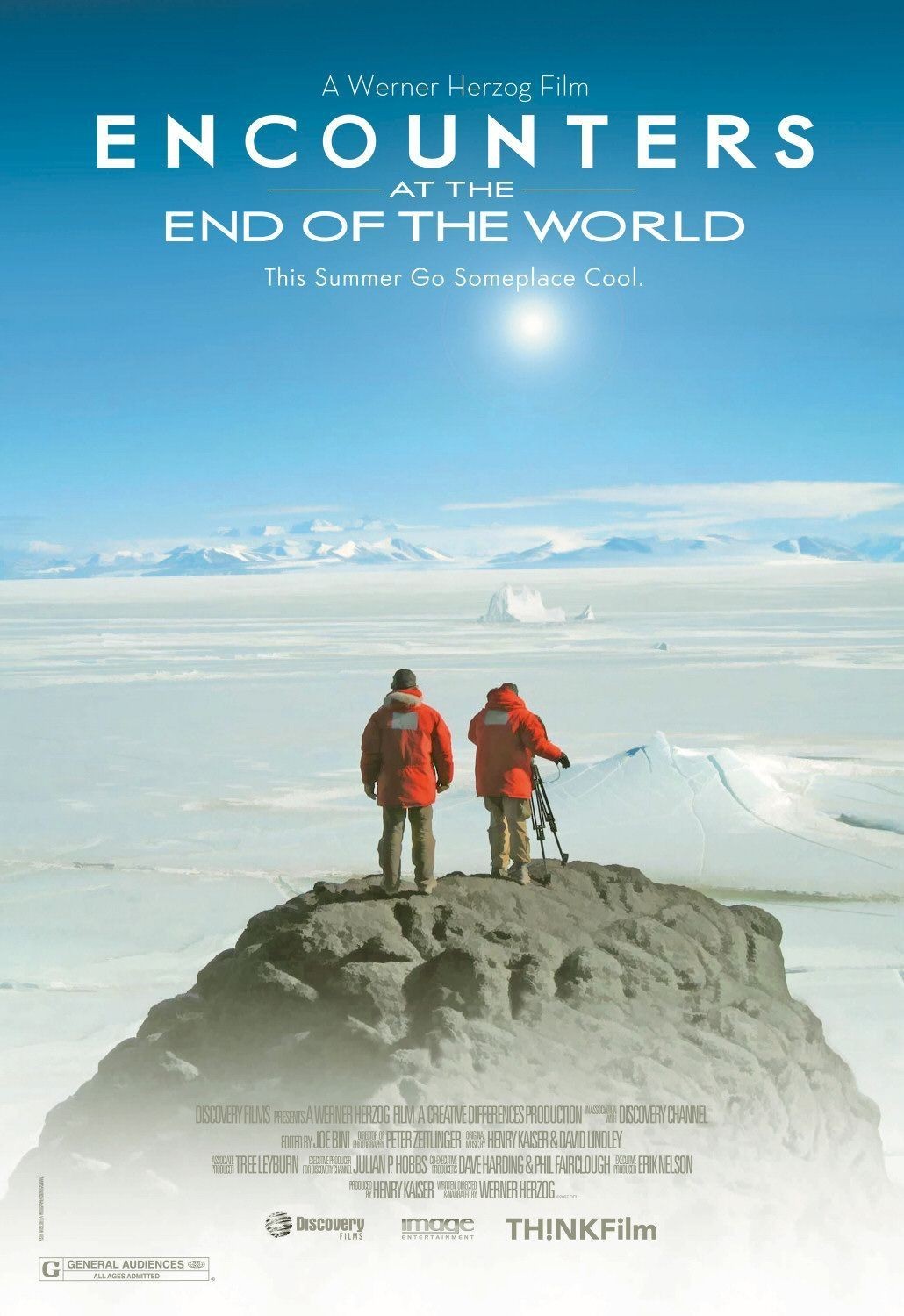

Read the title of “Encounters at the End of the World” carefully, for it has two meanings. As he journeys to the South Pole, which is as far as you can get from everywhere, Werner Herzog also journeys to the prospect of man’s oblivion. Far under the eternal ice, he visits a curious tunnel whose walls have been decorated by various mementos, including a frozen fish that is far away from its home waters. What might travelers from another planet think of these souvenirs, he wonders, if they visit long after all other signs of our civilization have vanished?

Herzog has come to live for a while at the McMurdo Research Station, the largest habitation on Antarctica. He was attracted by underwater films taken by his friend Henry Kaiser, which show scientists exploring the ocean floor. They open a hole in the ice with a blasting device, then plunge in, collecting specimens, taking films, nosing around. They investigate an undersea world of horrifying carnage, inhabited by creatures so ferocious, we are relieved they are too small to be seen. And also by enormous seals who sing to one another. In order not to limit their range, Herzog observes, the divers do not use a tether line, so they must trust themselves to find the hole in the ice again. I am afraid to even think about that.

Herzog is a romantic wanderer, drawn to the extremes. He makes as many documentaries as fiction films, is prolific in the chronicles of his curiosity and here moseys about McMurdo, chatting with people who have chosen to live here in eternal day or night.

They are a strange population. One woman likes to have herself zipped into luggage, and performs this feat on the station’s talent night. One man was once a banker and now drives an enormous bus. A pipefitter matches the fingers of his hands together to show that the second and third are the same length — genetic evidence, he says, that he is descended from Aztec kings.

But I make the movie sound like a travelogue or an exhibit of eccentrics, and it is a poem of oddness and beauty. Herzog is like no other filmmaker, and to return to him is to be welcomed into a world vastly larger and more peculiar than the one around us. The underwater photography alone would make a film, but there is so much more. Consider the men who study the active volcanoes of Antarctica, and sometimes descend into volcanic fumes that open to the surface, although they must take care, Herzog observes in his wondering, precise narration, not to be doing so when the volcano erupts. It happens that there is another movie opening today in Chicago that also has volcanic tubes (“Journey to the Center of the Earth“). Do not confuse the two. These men play with real volcanoes.

They also lead lives revolving around monster movies on video, and a treasured ice-cream machine and a string band concert from the top of a Quonset hut during the eternal day. And they have modern conveniences of which Herzog despairs, like an ATM machine, in a place where the machine, the money inside it and the people who use it, must all be air-lifted in. Herzog loves these people, it is clear, because like himself they have gone to such lengths to escape the mundane and test the limits of the extraordinary. But there is a difference between them and Timothy Treadwell, the hero of “Grizzly Man,” Herzog’s documentary about a man who thought he could live with bears and not be eaten, and was mistaken. The difference is that Treadwell was a foolish romantic, and these men and women are in this god-forsaken place to extend their knowledge of the planet and of the mysteries of life and death itself.

Herzog’s method makes the movie seem like it is happening by chance, although chance has nothing to do with it. He narrates as if we’re watching movies of his last vacation — informal, conversational, engaging. He talks about people he met, sights he saw, thoughts he had. And then a larger picture grows inexorably into view. McMurdo is perched on the frontier of the coming suicide of the planet. Mankind has grown too fast, spent too freely, consumed too much, and the ice cap is melting, and we shall all perish. Herzog doesn’t use such language, of course; he is too subtle and visionary. He is nudged toward his conclusions by what he sees. In a sense, his film journeys through time as well as space, and we see what little we may end up leaving behind us. Nor is he depressed by this prospect, but only philosophical. We came, we saw, we conquered, and we left behind a frozen fish.

His visit to Antarctica was not intended, he warns us at the outset, to take footage of “fluffy penguins.” But there are some penguins in the film, and one of them embarks on a journey that haunts my memory to this moment, long after it must have ended.

Note: Herzog dedicated this film to me. I am deeply moved and honored. The letter I wrote to him from the 2007 Toronto Film Festival is at rogerebert.com