It’s an awful feeling for an artist, having a beloved work be put to sinister and destructive purposes. Once a work is out in the world, the artist has no control over it: everyone who makes art understands this on an abstract level. But to actually see it happen is something else entirely.

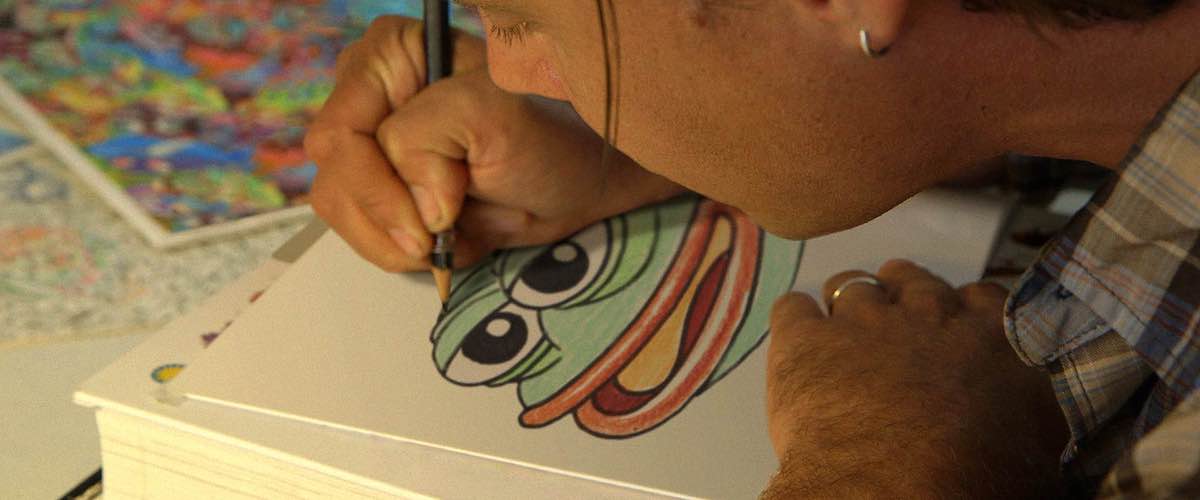

That’s what happened to comics creator Matt Furie, the protagonist of “Feels Good Man,” a documentary directed by Furie’s close friend, artist Arthur Jones. Furie invented Pepe the Frog, a bug-eyed stoner amphibian with a vibe in the vicinity of Cheech and Chong or Jeff Lebowski. Then, over an increasingly agonizing period of years, he saw the character appropriated by other people (including celebrities), then refashioned as the mascot of the so-called alt-right, a decentralized right-wing political subculture obsessed with sowing uncertainty and chaos through trolling.

You’ve likely seen the image of Calvin from the classic comic strip “Calvin & Hobbes” peeing on a symbol of some designated enemy while staring at the viewer with a malicious expression. The image never appeared in the original strip, but over the past 25 years, it has spread all over the world, focusing on targets from Florida State University’s football team to various NASCAR drivers and, in 1996, the boss of some disaffected police officers (the officers got suspended without pay for spreading images of Calvin urinating on their hated supervisor). Bootleg t-shirts and decals from fly-by-night companies spread the micturating Calvin without authorization from comic strip creator Bill Watterson and his publisher, United Press International. The rights-holders tried to prosecute the people responsible, but had to give up because there were too many and they were too elusive.

A similar thing happened with Pepe, on a grander scale. As chronicled in “Feels Good Man,” Furie, who has been obsessed with frogs since childhood, introduced the character in 2005 in his comic series “Boy’s Club.” Pepe was appropriated in fitness videos first. Furie let it go.

Then Pepe became an emblem on 4chan message boards, where users took pride in inflicting emotional distress on strangers in such a way as to maintain deniability about what they were doing. The frog’s expression—as described by other illustrators and meme experts consulted for the film—had an ugly Mona Lisa aspect. Inscrutable yet knowing. Superficially blasé or innocent, but at the same time, conscious and responsible. Your gut told you that this frog was up to no good, but you couldn’t prove it.

“Feels Good Man” is essentially a detective story, tracking the appropriation of an artist’s work for purposes that go against everything he’s about. Not content to string together talking head interviews, the movie uses art and animation to find a cinematic equivalent for Pepe’s evolution from a quirky cartoon animal into a weapon.

One of the more fascinating substrains of the story shows how 4chan users began to act as if they, not Furie, invented and owned Pepe. Once modified/distorted Pepe images migrated off message boards and onto social media, they were put to different, often self-serving uses in the mainstream (even getting borrowed by celebrities Katy Perry and Nicki Minaj). The people who had stolen and altered Pepe went all-out to “reclaim” the character from so-called “normies”—a warped-mirror version of Furie’s legitimate quest.

Things got worse after Pepe started being presented as the Mickey Mouse or SpongeBob Squarepants of authoritarian fascist fanboys: an outwardly “harmless” or “innocent” badge for anyone who’s into right-wing disinformation, shitposting, and targeted cruelty. Right-wing hate culture had been driven mostly underground in regular life (although of course there were eruptions here and there—and since the ’90s, hateful messages had been spread daily over public airwaves via Rush Limbaugh, Michael Savage, Alex Jones, Fox News Channel, Breitbart News, and the like). During the late aughts and early teens, this tendency moved out of the shadows and into political daylight, in response to demographic shifts in the U.S., eight years of governance by the first Black president, and a growing alarm among some white Americans that political and cultural power sharing was in their future, and would not be optional.

Racism, sexism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia, flat-out nihilistic glee at another person’s misfortune: if that kind of sentiment found its way into a Tweet or Facebook post, there was a good chance Pepe was there with it, as an avatar or uploaded graphic. Sometimes Pepe was wearing a swastika, a Ku Klux Klan hood or a Make America Great Again cap. Other times, he was just Pepe. But he always had that unsettling expression. Maybe Pepe endorsed the message. Maybe he just spread it to upset others. It was hard to say for sure.

Once Donald Trump entered the race for the Republican presidential nomination and based his campaign around shouting things that American reactionaries had been conditioned to whisper—or just not say—Pepe became associated with Trump supporters, then with Trump himself. Trump’s rise was perfectly aligned with a political strain that specialized in initiating or amplifying distress and disorder, getting its rocks off on the aftermath while leaving just enough of a grey area in terms of intent that the targets felt gaslit. (One source in the film describes the appropriated Pepe as an “impossible mixture of innocence and evil.”)

An image of Pepe with Trump’s angel-hair-pasta pompadour spread over the Internet. Then Trump retweeted it in October, 2015, and the association became official. A once-cartoon amphibian was linked to a gangster president who held power through chaos and fear. The most chilling moment reconstructs message board traffic during a public appearance by Trump’s Democratic opposition, Hillary Clinton. An alt-right supporter in the room yelled “Pepe!” at Clinton after being egged on to do so. “To the white supremacist, anti-Semitic, neo-Nazi alt right in this country, that was a moment of triumph,” MSNBC host Rachel Maddow noted later.

Pepe was been turned into something he was never intended to be. His creator and steward didn’t realize what was occurring until it was too late to halt or reverse it. The film’s chronicle of Furie’s increasing despair and disillusionment syncs up with changes in the United States’ collective character and self-image. “Feels Good Man” links the hijacking of one cartoonist’s intellectual property with the hijacking of a nation’s norms, laws, and institutions: a decentralized campaign of subversion, perversion, theft, and distortion, happening mostly out of sight for a long time, then finally emerging into daylight, secure in the belief that the pivotal damage had already been done, and there was no going back to how things were.