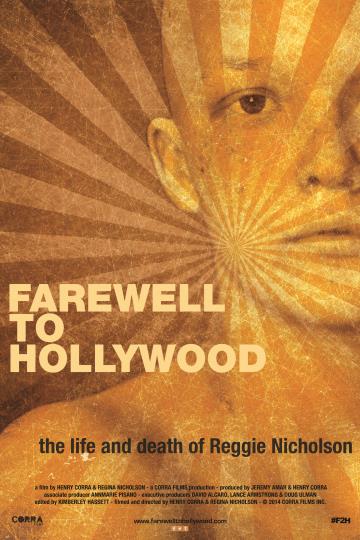

Watching a truly lovely and spirited teenage girl die of cancer will not, let’s face it, strike some viewers as a great night at the movies. But documentary films often find their value in taking us to places that are challenging, even painful. “Farewell to Hollywood” offers the rewarding difficulties of that type of filmmaking, along with additional challenges that stem from questions about its own ethics.

The film’s direction is credited to Henry Corra and Regina Nicholson, and in that fact lies the key to its origins and unusual nature. Corra, a veteran nonfiction filmmaker in his late 50s, met 17-year-old aspiring cineaste Nicholson four years ago at a film festival (where she had an award-winning short, a fact that is curiously not mentioned in this film). Diagnosed with terminal cancer, she wants to make a feature film before she dies, and he agrees to help her. “Farewell to Hollywood” documents the time following that decision until her death two years later.

Despite their many obvious differences, the two collaborators are well-matched. Nicholson, who’s known as Reggie, is a major film buff whose fascination with movies such as “Silence of the Lambs,” “Pulp Fiction” and “Apocalype Now” drives her filmmaking ambitions and gives this doc a tinge of the meta-cinematic. For his part, Corra spent several years working for the Maysles brothers after encountering “Grey Gardens,” yet he sees his brand of “living cinema” as replacing their intended fly-on-the-wall objectivity with an immersive emotional involvement with his subjects.

In keeping with Corra’s vérité background, the film follows Reggie’s accelerating illness in a fluid, matter-of-fact, sometimes almost impressionistic way, with no interviews, narration or explanatory titles besides one at the beginning. Therein lies its sensory beauty as a work of art (the cinematography is limpid and intimate throughout), but also some of its weaknesses as a narrative account of certain events, subjects and personalities.

Of the various people we see in Reggie’s life, the most important to “Farewell to Hollywood,” besides Corra, are her parents. That in itself is not surprising, but the way the relationship evolves is very surprising, and perplexing. When we first meet them, the dad seems somewhat withdrawn, perhaps due to lingering shock over his daughter’s diagnosis. Mom, on other hand, comes across as level-headed and determined to support Reggie in every way she can. Over the ensuing months, though, this family fractures in ways that are hard on all involved, yet not easily understood.

Some of it, no doubt, comes from stresses common to many parents and teenagers. Reggie, willful and wanting to be her own person, says that her mom doesn’t like that she’s not the adoring little girl of childhood. Cancer adds another big dimension of tension, one that’s surely hard for people who’ve not been there to fully grasp. And the filmmaking itself becomes a problem. Though her folks are initially supportive of the project, as if it would be an innocuous bit of therapy, they eventually grow very hostile to it and to Corra – the father accuses the filmmaker of having an affair with his daughter, a charge that seems patently absurd.

Filmmaking stops a while, and its eventual resumption doesn’t indicate any improvement in relations. On the contrary, after Reggie turns 18, she’s no longer her folks’ responsibility and they push her out of their lives (she appears to have no siblings); Corra evidently becomes her chief caregiver and closest companion.

As if cancer weren’t bad enough, this family meltdown is painful stuff. That the parents come off badly is undeniable, yet it seems like there are two basic explanations for their actions: they are really rotten people, or they’re ordinary people who are so freaked out by their daughter’s illness—and perhaps by other things we don’t see—that they react reflexively by banishing her from contact with them. Which is it?

This is an important question, but it’s one that we can’t easily answer from watching “Farewell to Hollywood.” Did Corra offer the Nicholsons a chance to tell their side of the story? He doesn’t say. Such omissions and elisions suggest why the film was controversial on the festival circuit. Clearly, Reggie wanted Corra in her life and actively helped shape the film’s depiction of her. But others weren’t so willing or able to exercise control, which is why some viewers have questioned the film’s ethics.

In this case, ethics are surely bound up with aesthetics, in a problematic way. One of the drawbacks of vérité comes from a kind of puritanism that, like much such, pretends to a kind of moral superiority: the implied sense that filmmaking which uses techniques like interviews and narration is inherently inferior, more rhetorical and less directly truthful. But surely vérité’s chief appeal is aesthetic, and rhetorical in a different way: rather than information, it gives us a seamless dreamlike experience like those of dramatic films.

Sometimes, though, information is a good thing. Much about “Farewell to Hollywood” ends up being more opaque than it should be, including Corra himself. He rarely conveys a sense of who he is and how he feels about the events he is not only chronicling but actively shaping. If this were set up as an equal collaboration, why didn’t Reggie turn the camera on him? Another curiosity is that they are almost never shown talking about film, including the making of this one, which must have involved thousands of decisions.

Corra has said that Reggie saw a three-hour cut of the film a few weeks before she died (the final version runs 102 minutes) and gave her notes. Let’s hope she found the lineaments of the film she intended to make. As hard as it is to watch her physical deterioration and suffering, she comes across as an ordinary teenager who’s also a very remarkable person, and that helps make “Farewell to Hollywood” a powerfully emotional and moving experience, questions about its methods aside.