Ernest Cole was a name almost lost to history. The South African photographer made headlines around the world with his incisive on-the-ground photos of the effect on apartheid in his home country in the late 1960s. Forced to flee the state to publish his one–and sadly only–book, “House of Bondage,” Cole gained an international audience. But then he found his would-be employers, buyers and funders were only interested in his photography capturing the worst of human suffering, racism, and destitution. Frustrated by the limitations put on his artistic career, Cole’s work declined, projects were never completed, and by the 1980s, the once celebrated photographer was homeless living in exile in New York City before cancer claimed him in 1990 – the same year his fellow countryman Nelson Mandela was released from prison.

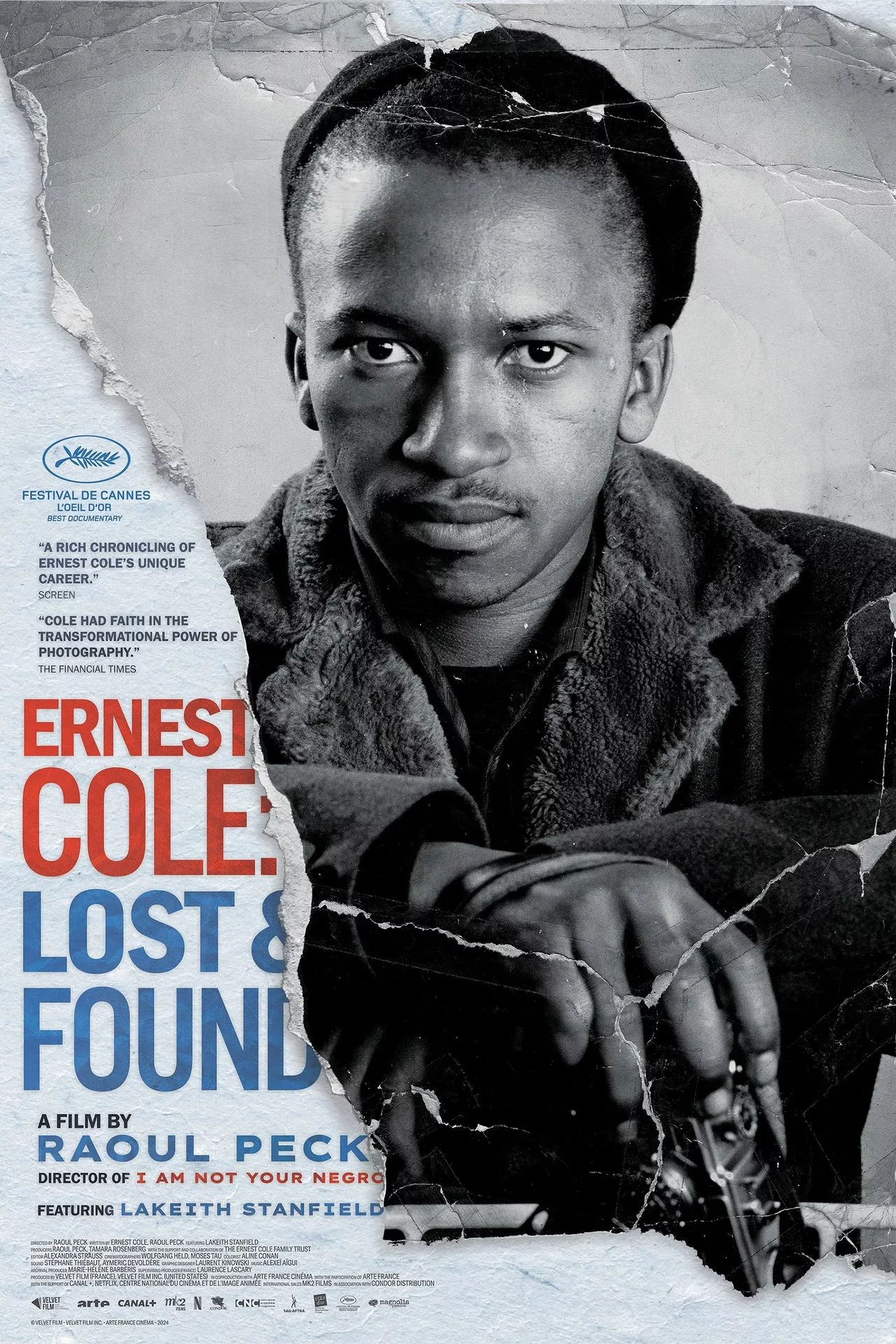

Raoul Peck’s tribute to the unsung photographer, “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found,” follows its subject’s journey from his hometown in South Africa to his troubled final years and even beyond, as his story gains new life after 60,000 of his negatives and numerous notebooks were returned to his family from a Swedish bank. From Cole’s own words and interviews with his friends and loved ones, Peck writes a thorough narrative through the highs and lows of the photographer’s life, including details about his childhood in South Africa and many years of homesickness abroad. We learn that Cole was influenced by artist Henri Cartier-Bresson and began documenting the world around him in banal slice of life shots, unveiling the likes of how Black men were treated in South African prisons, the segregated entrances that pockmarked the country, the far flung banishment camps where exiles were shipped away from their families, and many other atrocities. Actor LaKeith Stanfield voices Cole with a mournful tone, a somber, stroic performance that rips through the film’s fabric. Peck, who shares a co-writing credit with Cole, moves the narrative from past to present, engaging with the audience directly, which can be a strange thing to imagine from a man who died over 30 years ago.

The most vivid aspect of the documentary is Peck’s use of Cole’s photography, using his street scene snapshots from South Africa, New York, North Carolina, California, Mississippi, Illinois, Washington D.C., and Tennessee to illustrate his life’s journey and the systemic oppression his camera witnessed with alarming frequency. While most of the photos in the film are Cole’s and in black-and-white, occasional pops of color light up the screen thanks to his eye for intense hues and composition, showing a subtle passing of time from the 1960s to the ‘70s and ‘80s. The photos could be mundane shots of “whites only” signs, pictures of police officers questioning young boys on the street, or the number of Black domestic workers toiling for white employers and how similar they seemed on either side of the Atlantic. These images are powerful on their own, yet some of the editing and transitions feel less polished, distracting the viewer from the photographs themselves. Like in many of his previous films like “I Am Not Your Negro,” “Silver Dollar Road,” and “Lumumba: Death of a Prophet,” Peck finds such parallels between the past and the present and scatters them throughout the film, tying Cole’s work of 40 or even 50 years ago to today’s problems, like the ongoing rise of xenophobia against migrants in South Africa. It also explores unspoken issues, like how living in exile pushed Cole and some of his contemporaries to dark thoughts.

Peck also contextualizes certain moments in Cole’s life with what was going on in the world, like how Miriam Makeba spoke out at the UN in the early 1960s and boycotts were starting to form against South Africa over apartheid around the time he began documenting his surroundings. In the late 1960s, the assassination of South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd helped spike interest in Cole’s work and led to his book “House of Bondage,” which further spilled his country’s shameful secrets. The late 1960s also saw tumult in different corners of the world, from Vietnam to the U.S., Argentina, France and more. Cole’s book was quickly banned in South Africa, but his photos endured, especially after the mysterious set of circumstances that resurfaced tens of thousands of his photographs, many of which had never been seen before.

“I never stopped photographing for a single moment,” Stanfield as Cole tells the audience, and indeed, the photographs Peck lays out show a life lived far beyond the one book that earned him fame and homesickness. A mixture of music from the era and Alexei Aigui’s propulsive score keeps the documentary flowing from one difficult confession to the next insightful observation, like when Cole sees the similarities between apartheid and Jim Crow laws, a finding that likely did not endear him to a number of Americans. Notably, Peck spends so much time unpacking Cole’s inner life from his diaries and notebooks, because while the photos may live on in archives, those are the stories most at risk of disappearing from the frame. “The total man does not live for one experience,” Cole says as the documentary begins. Yet, Cole’s story is still unfolding with this strange new chapter. This renewed interest and Peck’s reintroduction might give a wider audience the chance to appreciate the photographer on his own terms.