World War II may have been won by our side because of what British code-breakers accomplished at a countryside retreat named Bletchley Park.

There they broke, and broke again, the German code named “Enigma,” which was thought to be unbreakable, and was used by the Nazis to direct their submarine convoys in the North Atlantic. Enigma was decoded with the help of a machine, and the British had captured one, but the machine alone was not enough. My notes, scribbled in the dark, indicate the machine had 4,000 million trillion different positions–a whole lot, anyway–and the mathematicians and cryptologists at Bletchley used educated guesses and primitive early computers to try to penetrate a message to the point where it could be tested on Enigma.

For those who get their history from the movies, “Enigma” will be puzzling, since “U-571” (2000) indicates Americans captured an Enigma machine from a German submarine in 1944. That sub is on display here at the Museum of Science and Industry, but no Enigma machine was involved. An Enigma machine was obtained, not by Americans but by the British ship HMS Bulldog, when it captured U-110 on May 9, 1941.

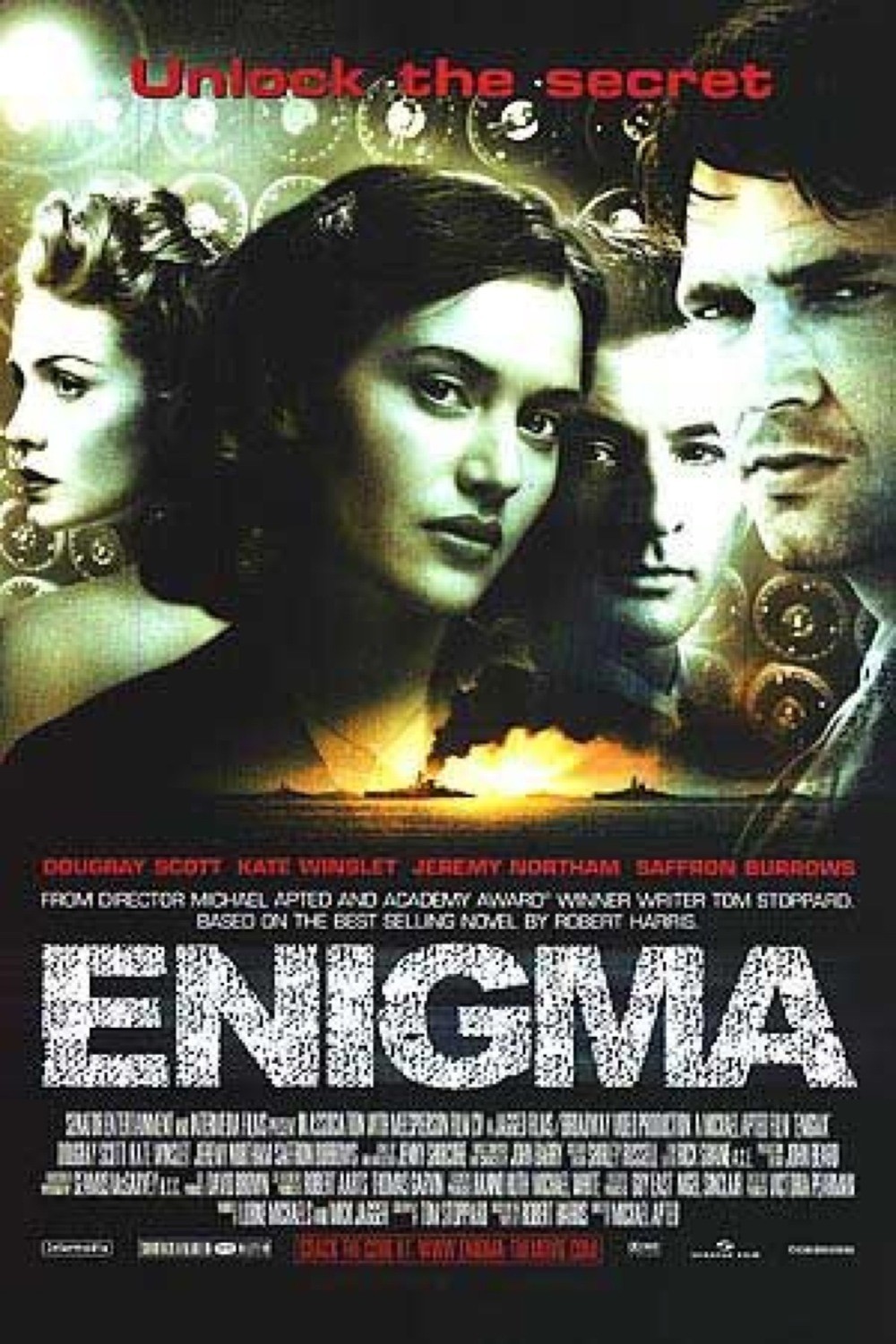

Purists about historical accuracy in films will nevertheless notice that “Enigma” is not blameless; it makes no mention of Alan Turing, the genius of British code-breaking and a key theoretician of computers, who was as responsible as anyone for breaking the Enigma code. Turing was a homosexual, eventually hounded into suicide by British laws, and is replaced here by a fictional and resolutely heterosexual hero named Tom Jericho (Dougray Scott). And just as well, since the hounds of full disclosure who dogged “A Beautiful Mind” would no doubt be asking why “Enigma” contained no details about Turing’s sex life. The movie, directed by the superb Michael Apted, is based on a literate, absorbing thriller by Robert Harris, who portrays Bletchley as a hothouse of intrigue in which Britain’s most brilliant mathematicians worked against the clock to break German codes and warn North Atlantic convoys. As the film opens, the Germans have changed their code again, making it even more fiendishly difficult to break (from my notes: “150 million million million ways of doing it,” but alas I did not note what “it” was). Tom Jericho, sent home from Bletchley after a nervous breakdown, has been summoned back to the enclave because even if he is a wreck, maybe his brilliance can be of help.

Why did Jericho have a breakdown? Not because of a mathematical stalemate, but because he was overthrown by Claire Romilly (Saffron Burrows), the beautiful Bletchley colleague he loved, who disappeared mysteriously without saying goodbye. Back on the job, he grows chummy with Claire’s former roommate Hester Wallace (Kate Winslet), who may have clues about Claire even though she doesn’t realize it. Then, in a subtle, oblique way, Tom and Hester begin to get more than chummy. All the time Wigram (Jeremy Northam), an intelligence operative, is keeping an eye on Tom and Hester, because he thinks they may know more than they admit about Claire–and because Claire may have been passing secrets to the Germans.

Whether any of these speculations are fruitful, I will allow you to discover. What I like about the movie is its combination of suspense and intelligence. If it does not quite explain exactly how decryption works (how could it?), it at least gives us a good idea of how decrypters work, and we understand how crucial Bletchley was–so crucial its existence was kept a secret for 30 years. When the fact that the British had broken Enigma finally became known, histories of the war had to be rewritten; a recent biography of Churchill suggests, for example, that when he strode boldly on the rooftop of the Admiralty in London, it was because secret Enigma messages assured him there would be no air raids that night.

The British have a way of not wanting to seem to care very much. It seasons their thrillers. American heroes are stalwart, forthright and focused; Brits like understatement and sly digs. The tension between Tom Jericho and Wigram is all the more interesting because both characters seem to be acting in their own little play some of the time, and are as interested in the verbal fencing as in the underlying disagreement. It is a battle of style. You can see similar fencing personalities in the world of Graham Greene, and of course it is the key to James Bond.

Kate Winslet is very good here, plucky, wearing sensible shoes, with the wrong haircut–and then, seen in the right light, as a little proletarian sex bomb. She moves between dowdy and sexy so easily, it must mystify even her. Claire, when she is seen, is portrayed by Saffron Burrows as the kind of woman any sensible man knows cannot be kept in his net–which is why she attracts a masochistic romantic like Tom Jericho, who sets himself up for his own betrayal. If it is true (and it is) that “Pearl Harbor” is the story of how the Japanese staged a sneak attack on an American love triangle, at least “Enigma” is not about how the Nazis devised their code to undermine a British love triangle. That is true not least because the British place puzzle-solving at least on a par with sex, and like to conduct their affairs while on (not as a substitute for) duty.