Jack Nicholson’s “Drive, He Said” is a disorganized but occasionally brilliant movie about two college students and the world they, and we, inhabit. Their campus is a microcosm of the least reassuring aspects of contemporary America; the two overwhelming mental states are paranoia and compulsive competitiveness. Sufferers from both conditions are obsessed by the fear that something might be gaining on them. In “Drive, He Said,” the paranoic student is afraid of the draft, the System, and They, whoever They are. The other student is a star basketball player, or, as his friends tell him, “You stay after school to run around in your underwear.” His fears are more general and vague and, therefore, more frightening.

The movie has a sort of jumpy, nervous rhythm, as if it were on speed, and sometimes that works but it’s finally just distracting. The problem is that the stories of the two main characters don’t mesh. They’re roommates, to be sure, but that’s a tenuous connection. And when the paranoid (Michael Margotta) has his three big adventures freaking out at the draft physical, attacking a faculty wife, and freeing all the animals in a biology lab the scenes feel like set pieces, unrelated to the movie.

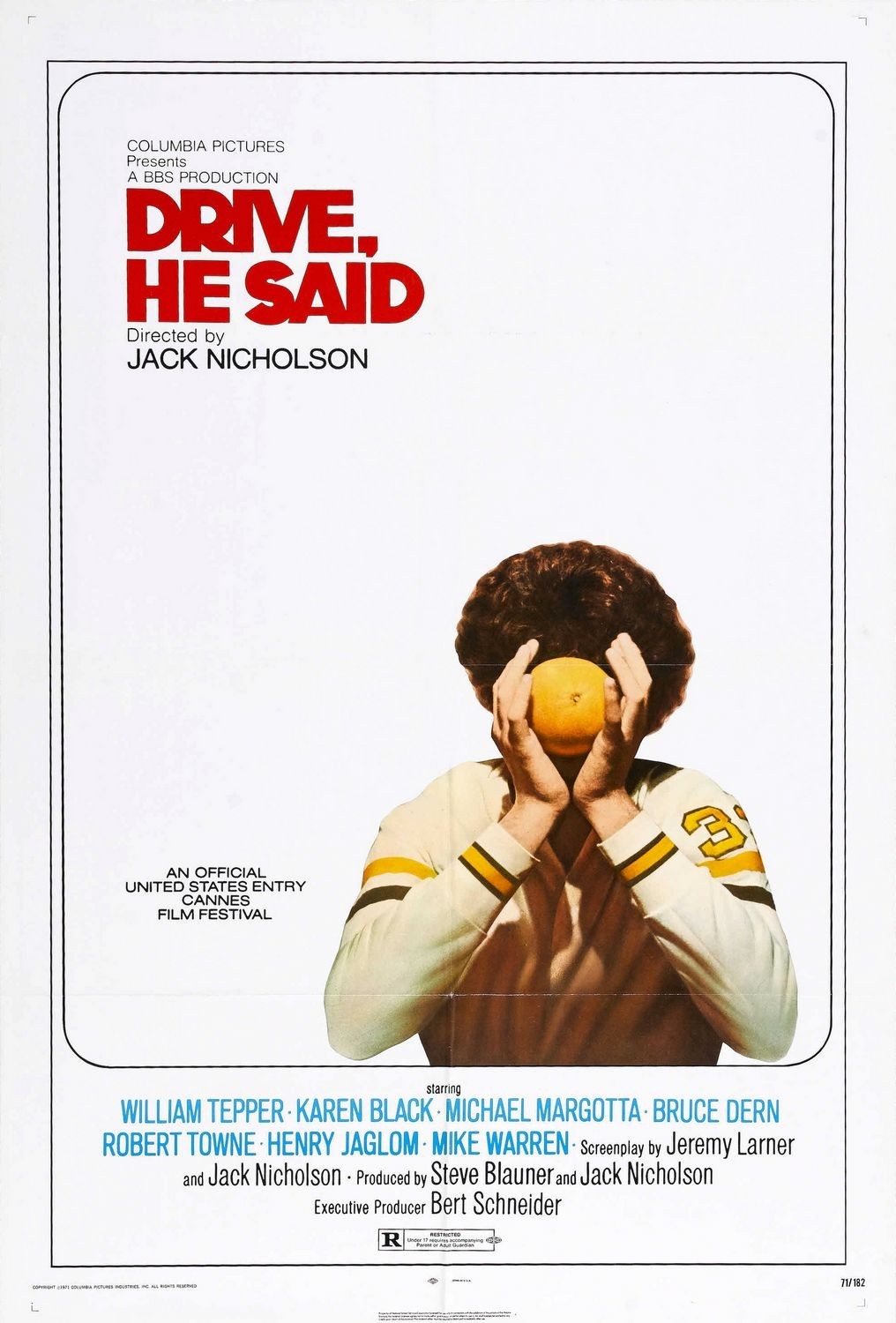

The movie that surrounds them involves Hector (played with laconic charm by William Tepper), who plays basketball not because he’s a jock but because he enjoys the self-testing that the game involves. By the time we meet him, he has become a star and a prime choice for the pro draft, but, well, somehow the whole thing is falling apart on him.

One of his problems is the faculty wife, played by Karen Black. He has been having an affair with her, but she breaks it off just as he discovers, uncomfortably, that he might be in love. And then it turns out she’s pregnant. This is a real-life experience of the most unsettling sort, and makes it difficult for him to take basketball as seriously as his coach thinks he should.

The coach is an intense competitor who positively believes in all the values, moral and physical, that have been preached by all coaches since the dawn of time-outs. Bruce Dern’s performance as the coach, by the way, is a small masterpiece of accurate observation.

The performances, indeed, are the best thing in the movie. Nicholson himself is a tremendously interesting screen actor, and he directs his actors to achieve a kind of intimacy and intensity that is genuinely rare. But if Nicholson is good on the nuances, he’s weak on the overall direction of his film. It doesn’t hang together for us as a unified piece of work.

I have a notion he may have been trying for an effect similar to that in his three previous films as an actor (“Easy Rider,” “Five Easy Pieces,” and “Carnal Knowledge“), which were deliberately episodic and depended on the cumulative effect of the episodes for a structure that occurred to us only gradually. But the episodes refuse to come together in “Drive, He Said,” and what we’re left with are some very good scenes in search of a home.