Mike Nichols’ “Carnal Knowledge” opens on a darkened screen, and we hear the traditional Glenn Miller arrangement of “Moonlight Serenade.” And then we hear two young men earnestly talking of young women, and sex, and their ambitions in those two directions.

We learn that the first young man hopes to meet a high-class girl, one with morals, who will tell him things he never knew about himself. We learn that the second young man wants exactly that kind of girl too, only with big boobs. And then…

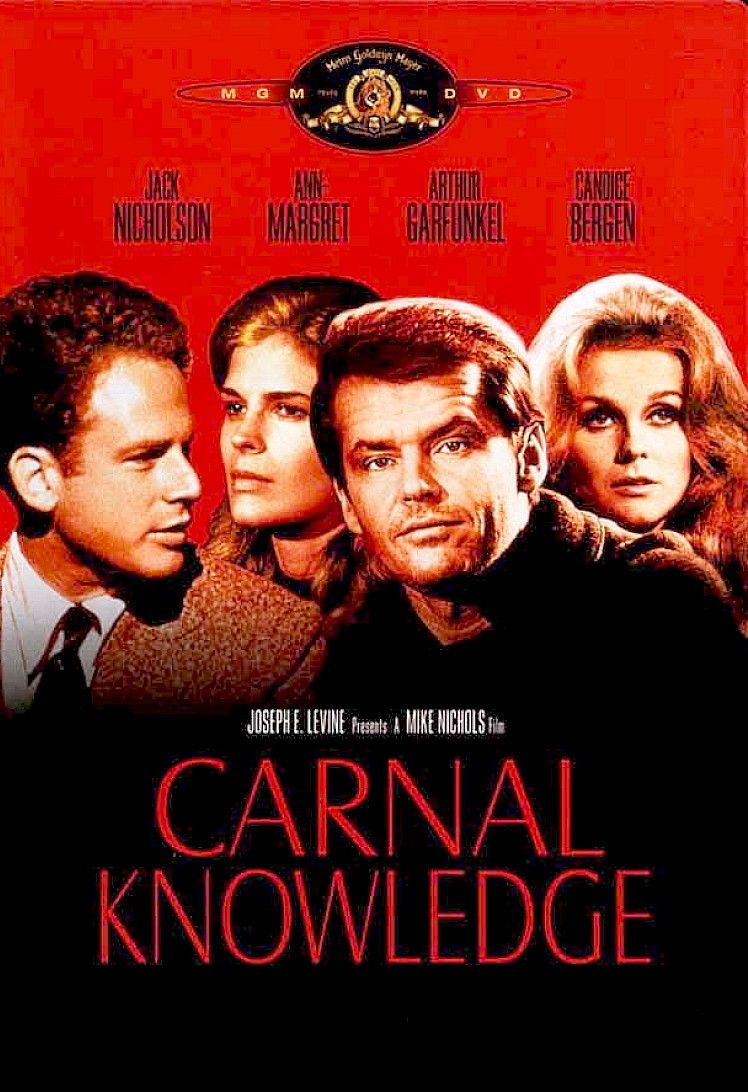

We find ourselves at a college mixer sometime in the late 1940s. Candice Bergen drifts past the two intense young men, who are leaning in a doorway and checking out the talent, and she finds herself a perch on a windowsill. “She’s yours. I’m giving her to you,” Jack Nicholson (who doesn’t have her to give) tells Art Garfunkel (who doesn’t know how to take her).

After a pep talk from Nicholson, Garfunkel finally musters the courage to wander over toward Miss Bergen, but he’s too shy to speak. He stops in front of her, pretends to look out the window at something tremendously interesting (if invisible) on the other side, and then returns to Nicholson, defeated.

With the perception and economy that mark their entire film, Nichols and his writer, Jules Feiffer, have established the theme of “Carnal Knowledge” in this handful of shots: The film will be about men who are incapable of reaching, touching or deeply knowing women.

We meet the two men during their college years, and follow them for maybe 20 years afterward as they drift through a marriage apiece and several frustrating liaisons with the kinds of women they think they desire. Both men rely a great deal on their supposed sexual prowess, but both are insecure sexually and the Nicholson character finally becomes impotent.

Their problem, to the degree they share one, is that they try to find their fantasy-woman in the flesh, and discover when the fantasy becomes real that the real woman is all too real for them to live with and understand. The thing is, they both want to be dominated by women — only not really.

“Carnal Knowledge” never finds its male characters at “fault,” exactly, and the movie isn’t concerned with fixing blame. It chooses the tragedy form, not the essay. At the end, we’re left with people who have experienced as much suffering as they’ve caused through their inability to accept women as fellow human beings. The Nicholson character is reduced to highly complicated charades with a prostitute (Rita Moreno), and the Garfunkel character is still kidding himself. In his early 40s, he’s grown a mustache and affected a hip life style and shacked up with a 17-year-old. “She may only be 17,” he tells his old classmate, “but in many ways, I’m telling you, she’s older than me.”

“Carnal Knowledge” is clearly Mike Nichols’ best film. It sets out to tell us certain things about these few characters and their sexual crucifixions, and it succeeds. It doesn’t go for cheap or facile laughs, or inappropriate symbolism, or a phony kind of contemporary feeling.

The Ann-Margret role is the best example, I think, of Nichols’ determination to stay within the diameters of his characters. Ann-Margret has been in a lot of bad movies, and done some bad acting in them, and this role (with makeup including a remarkably realistic artificial chest) could have degenerated into a parody with no trouble at all. Instead, it’s an artistic triumph.

Nicholson, who is possibly the most interesting new movie actor since James Dean, carries the film, and his scenes with Ann-Margret are masterfully played. Art Garfunkel tends to be a shade transparent, although not to the degree that the film suffers, and Candice Bergen is very good, but in the kind of role she plays too often, the sweet-bitchy-classy college girl.

As I’ve suggested, “Carnal Knowledge” stays within the universe of its characters, and inhabits it totally. And within that universe, men and woman fail to find sexual and personal happiness because they can’t break through their patterns of treating each other as objects.