Connection so fascinates us in our wired-in, modern times, but hardly any film has been able to speak inventively about it. Precautionary tales like “Disconnect” or “Men, Women & Children” have gone in one ear and out the other, no different from tedious Facebook posts griping that our phone usage must be the downfall of all communication. The irony of disconnection through connected tech proves too easy, the nostalgia for non-wired-in days too shallow.

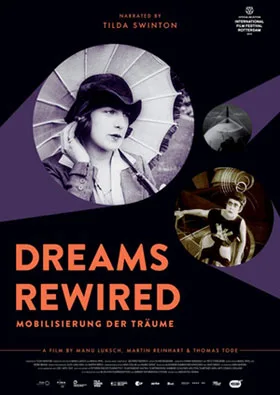

In floats “Dreams Rewired,” which took three directors (Martin Reinhart, Manu Luksch and Thomas Tode) to assemble. It feigns no resolution to the concerns of our screen-craziness. Instead, the ethereal essay provides a bounty of poetry, in the form of a measured narration by international treasure Tilda Swinton, and an extensively labored assembly of 200 black-and-white film clips.

These excerpts are unexpected, their arrangement thrilling, showing either documents of technology of the era or dreams from over a century ago of what would come next. Using work from filmmakers like Thomas Edison to George Méliès to Dziga Vertov to Alice Guy and much more, “Dreams Rewired” feels its way through a history of connecting technology. Without chronology to its subject matters or accompanying clips, the film benefits from being more than a history lesson as it treats these the phone, radio, and television, inventions beyond regular comprehension, with appropriate tinges of magic. In this project’s contagious wonder, these breakthroughs become ideas about something bigger than plastic, their expanse consistently affecting the stock market, world peace, how we talk to other people, etc.

Very curiously, if not stubbornly, the film is obsessed with how our modern realities were fantasies of the past. The story is not so much about evolution but perspective; there are no images of iPhones or computers, considering that only two snippets used in the movie date beyond the 1960s. Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” is one of the only films to be mentioned by name, and even then the landmark movie is celebrated most for its philosophical significance in how a growing art form enhances its experience to connect with an audience. Gaumont legend Alice Guy is given a shout-out as the “the first director of narrative films,” but it’s one of the few times facts ground this film in concrete history.

The meticulously-chosen clips are often hypnotic, but the instinctual narration is what grips the viewer. It’s not just the charismatic presence of Swinton, who is game for delicacy or comedy (sometimes doing impressions of the men and women on-screen), but a finite wisdom. “Geography is history,” Swinton ruminates, in succinct prose written by Mukul Patel. Like when she touches upon our “life in the cloud, with chance of blue skies,” we immediately compute—and feel—exactly what she means.