Well, I guess I’ve finally gotten over my thing for heist movies. I liked “Topkapi” and “Grand Slam’ and ‘The Hot Rock” and that perfect moment when they knocked out the wrong wall in “Big Deal on Madonna Street.” I relished all the conventions of the genre, like the electronic safecracking gimmicks and the pressuresensitive carpets and the nifty suction devices. And I liked the motivation, tooÑpure greed, unalloyed by higher sentiments.

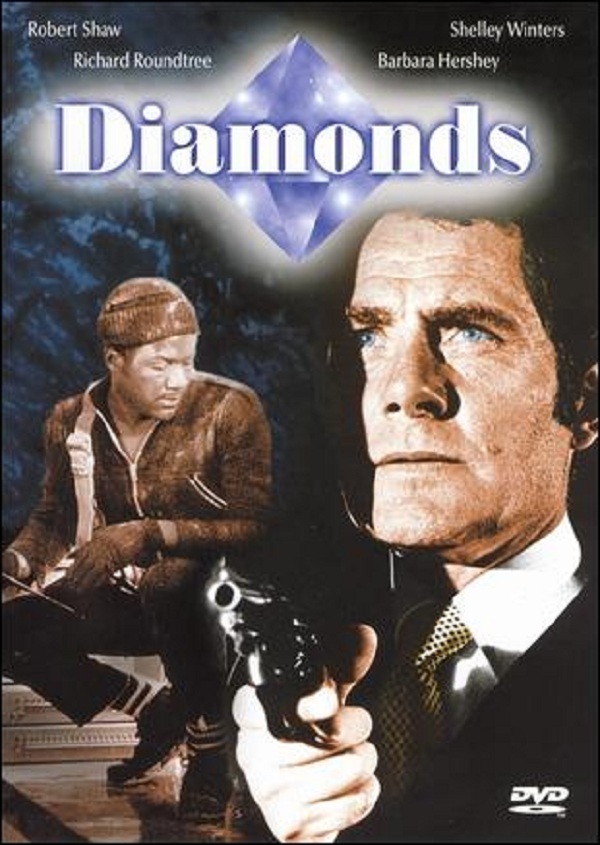

And so I was looking forward to “Diamonds.” The cast looked good, for one thing: Robert Shaw, always at his best in mean and crafty roles, and Richard Roundtree, who proved in “Shaft” that he has few peers when it comes to cracking heads, and Barbara Seagull, as the obligatory girl friend. And the movie even had Shelley Winters, who after “The Poseidon Adventure” has apparently settled down to a career as a stalwart Jewish matron. This time she’s a widow from Chicago looking for a new husband in Israel.

“Diamonds” was shot on location in Israel, apparently because the filmmakers became inspired by the enormous diamondtrading center in Tel Aviv. It’s a world center of diamondcutting, we’re told, and in its innards, far below street level, there’s a vault holding untold millions of dollars worth of gems. Shaw’s objective is to crack that vault. His twin brother designed it, you see, and their sibling rivalry is so intense that if one twin can make the safe, the other’s gotta break it. Roundtree comes along as the professional heist expert.

So far, so good, but any heist movie has to stand comparison with the masterpieces of the genre. We remember Peter Ustinov anchoring the rope in “Topkapi,” and the guy hanging upsidedown and putting the suction devices into place. And we remember that incredible expanding stainlesssteel contraption in “Grand Slam” that ran on compressed air and went above and then below the electric eyes so the thieves could get to the safe.

“Diamonds” just isn’t in that league. The ways in which Shaw and Roundtree get to the safe aren’t particularly ingenious, and, once they get there (and Roundtree has suspended himself in midair in front of the vault door), they have the combination to the lock! So they don’t have to drill little holes or use a stethoscope to listen to the tumblers moving inside. It’s all sort of a letdown.

But that’s nothing compared to what happens when they get inside the safe. And here, alas, my lips must remain sealed, because one unbreakable critics’ rule is that you can’t reveal how a heist movie turns out. But let me just sort of . . . hint. It turns out, incredibly, that Shaw’s motive isn’t greed at all. That he’s acting almost altruistically! That . . .

Well, it’s a disappointment for a cynic like myself. When I go to a heist movie, I want to be able to trust the people making the heist. I want to trust them to be greedy and selfish and run their hands through the diamonds and cry out “Mine! All mine!” Richard Roundtree works the “all mine!” bit for whatever it’s worth, but the movie’s ending is weak and unconvincing, and it seems to me that twin brothers should be able to work out their problems without involving us in a heist movie that doesn’t even have a heist.