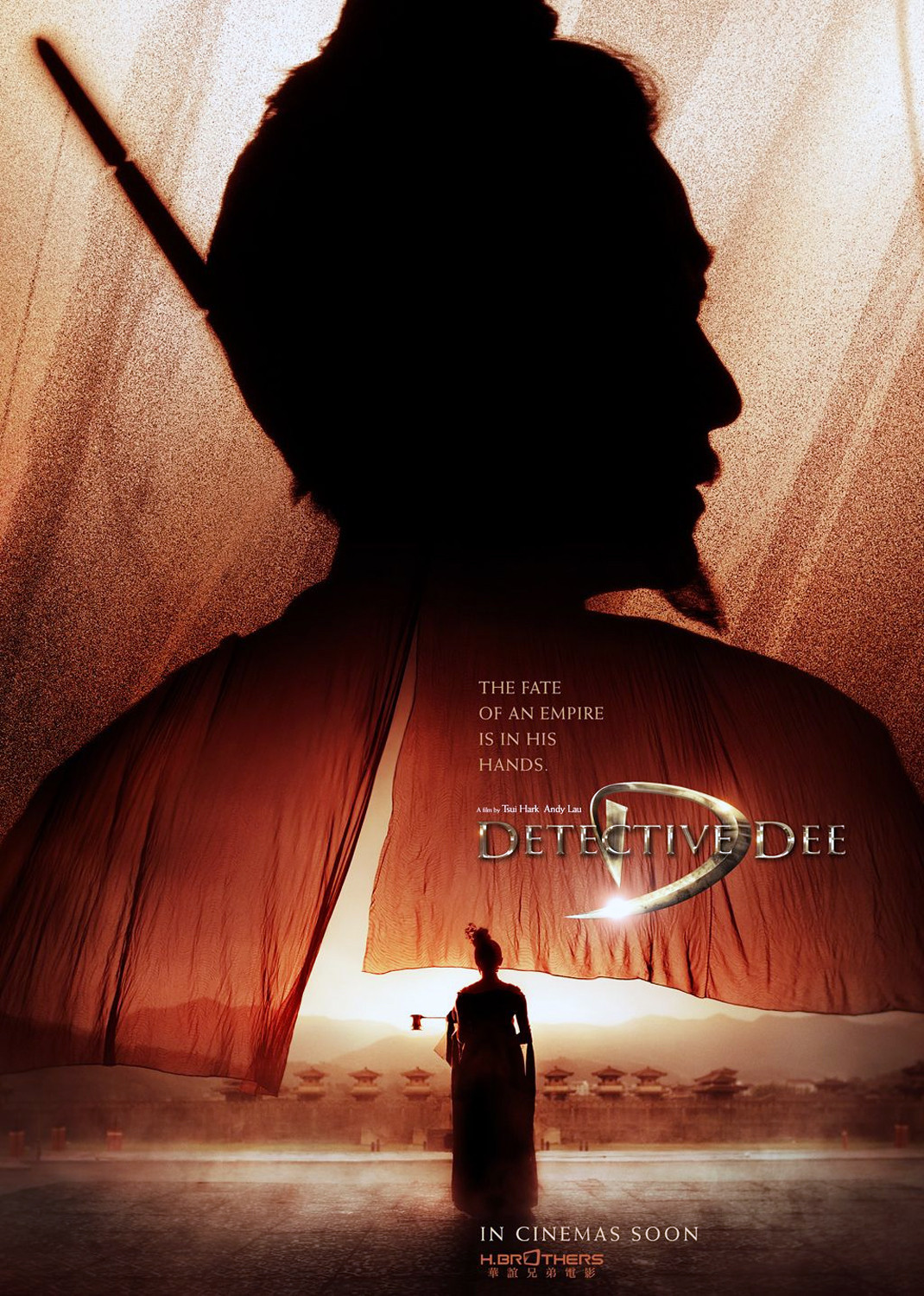

Detective Dee is a sleuth in China during the Tang Dynasty, circa 690. Like Sherlock Holmes, he based his detection largely on acute observation. He became famous in 17 mystery novels by Robert van Gulik, and now here he is in an extravaganza by Tsui Hark, a master of the choreography of action. “Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame” is a bewitching fantasy.

The empress Wu Zetian is about to become the first woman to ascend the Imperial Throne, but powerful forces scheme against her. A woman as head of state was no more thinkable in China in 690 than it is in America today. The construction of a towering statue of a giant Buddha is being hurried toward completion before her coronation day, when progress is interrupted by the spontaneous human combustion of one of its designers. Much as I persist in doubting it, such a form of death is allegedly possible, but surely there is no precedent for a series of them at such a touchy time.

It appears to be the perfect crime, if it is a crime. The victims combust in full view with no one nearby. There are of course no murder weapons. The cause is unknown, although it seems to happen in sunlight. This is a case for the greatest investigator in the land, and so Wu Zetian (Carina Lau) summons Detective Dee (Andy Lau) from the imperial prison, whence she cast him some years ago. As heroes in such situations often do, Detective Dee is forgiving, is still loyal to her and has apparently only improved his skills during confinement.

Now the stage is set for an epic of martial-arts action on a lavish scale, using vast sets which are both real and CGI. Tsui Hark is a genius of this genre, going back to the “Chinese Ghost Story” movies circa 1990 and nearly 60 other films, including “The Swordsman” and “Once Upon a Time in China” and its sequels. This film may represent the largest budget in his career, and one wonders how much of that went into the bizarre hair stylings of the empress.

On the basis of its scale, energy and magical events, this is the Hong Kong equivalent of a big-budget Hollywood blockbuster. But it transcends them with the stylization of the costumes, the panoply of the folklore, the richness of the setting, and the fact that none of the characters (allegedly) have superpowers. All the characters are presented as presumably real, with the exception of a talking stag — which, since it is an imperial stag, I suppose is permitted.

Detective Dee is assigned three assistants he is not sure he can entirely trust: Zhong (Tony Leung Ka-fai), who is an expert on the design and construction of the Buddha, and notices the missing scrolls; Jing’er (Li Bingbing), who enjoys the empress’ favor, and Pei (Chao Deng), a police official who seems fixed in a state of constant brooding. They debate with great energy while Dee listens and observes (as Holmes did), but events move inexorably toward disaster, as victims continue to incinerate, and it is discovered that the giant Buddha is just exactly high enough that if it fell in the wrong direction, it would land precisely on the site of the planned coronation. By this point there’s no reason to doubt that it would fall in that direction.

Tsui Hark began with the traditional techniques of martial-arts films, with athletic stars using concealed trampolines and invisible overhead wires to supplement their own considerable skills. One of the pleasures of watching traditional Bruce Lee or Jackie Chan films is that in many cases, the stars were actually doing what they seemed to be doing, much aided by editing and camera angles. Now those methods have been rendered obsolete by CGI, and the characters can leap any distance, defy gravity and virtually change direction in mid-air (when the laws of physics make that impossible). The humans here are as skilled as — well, as Kung Fu Panda.

The result lacks the exhilaration of watching Jackie Chan climb a wall or leap onto a truck in real time, but there’s an undeniable fluid grace. And masters like Tsui Hark prefer their action to have a certain visual continuity and not be fragmented into the incomprehensible bits of action employed by Michael Bay. His camera is also disciplined; his wide-screen compositions are elegant and almost classical, given the tumult on the screen.

That said, the movie exists very much in the moment, and although an attempt is made to flash back and reconstruct what must have happened, such explanations are required only by the conventions of the genre. In a way, Detective Dee is Sherlock Holmes, and we in the audience are slow-witted Watsons.