I once traveled for two days from Windhoek to Swakopmund through the Kalahari Desert, on a train without air conditioning, sleeping at night on a hard leather bench that swung down from the ceiling. That journey seemed a little shorter than the one that opens “Dead Man,” the new film by Jim Jarmusch.

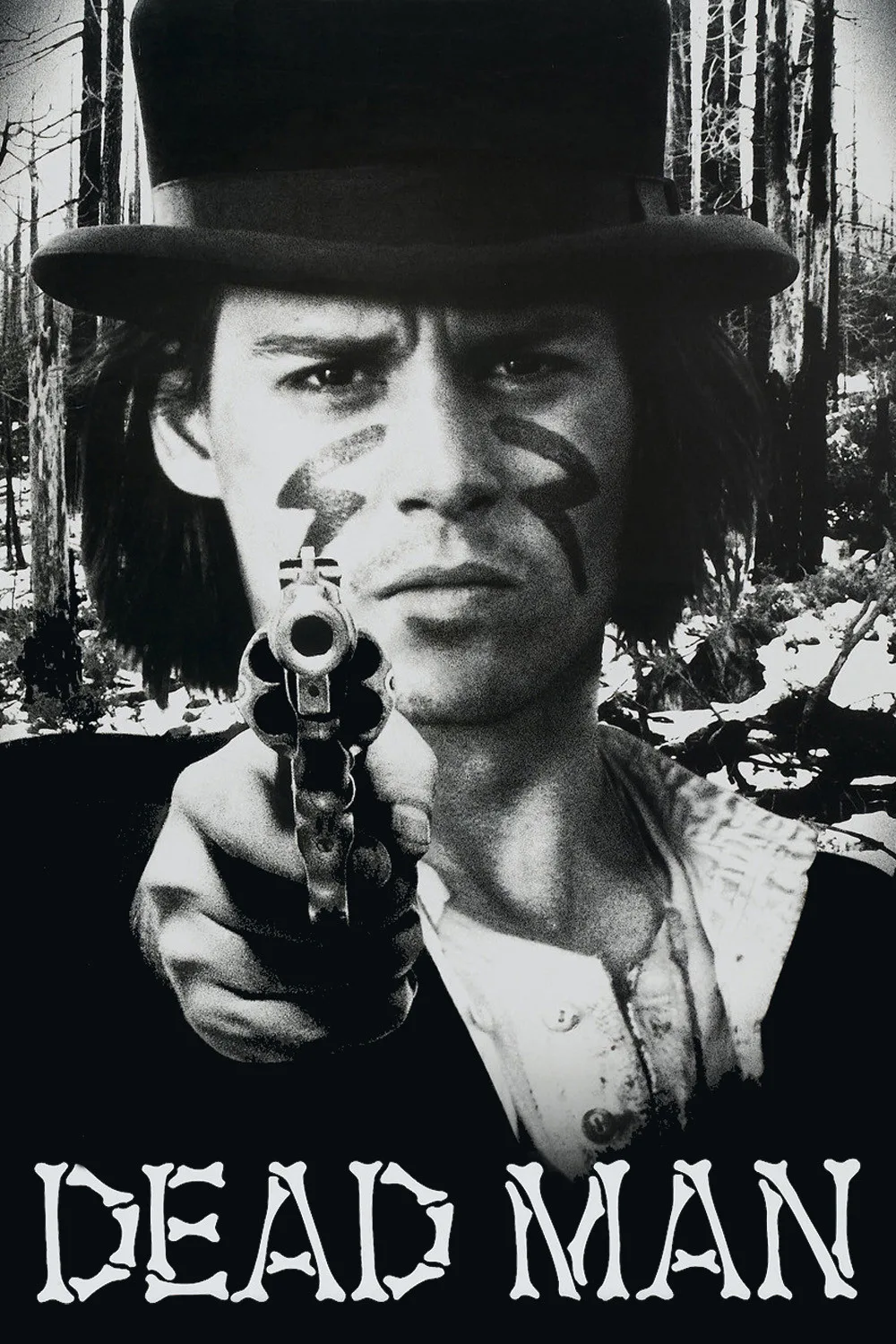

In the mid- to late 1800s, a man named William Blake (Johnny Depp) is traveling from Cleveland, where his parents have just died, to the Western town of Machine, where he has been promised a job. He is dressed in a checked suit that looks as if it had been waiting a long time in the menswear store for a sucker to come along. The train drones through the endless prairie. There are shots of the inside of the train. Shots of the view from the train. Shots of the train. Then the train’s soot-faced fireman warns Blake that his grave awaits him in Machine.

For some of my readers, the name William Blake will have rung a bell, and they will be wondering if there is any connection between this character and the mystical British poet who died in 1827. There is: They both have the same name. Our Blake has not heard of the English Blake, however, but before long he will run into an Indian named Nobody who can quote him by the yard.

We are getting ahead of the story. Blake arrives in Machine and reports to the Dickinson Steel Works, a dark, satanic mill where he expects to be employed as an accountant. The office manager (John Hurt) explains that the job no longer exists. Blake is appalled; he’s spent his last dime getting there. He confronts the owner of the mill (Robert Mitchum), who stands between a stuffed bear and a portrait of himself, which frame his fearful symmetry. Mitchum brandishes a shotgun and advises Blake to leave.

Blake befriends a hapless flower girl, and is invited to her room for an encounter between innocence and experience. Then the girl’s lover bursts in and shoots her. Blake shoots the man, is shot near the heart, leaps from the window, and flees. We discover the dead man is Dickinson’s son, and the mill owner hires men to track and kill Blake.

The next morning Blake regains consciousness in the forest to find his wound being tended by the Indian named Nobody (Gary Farmer), who was raised by white men, educated in England, and treats Blake as if he really is the poet.

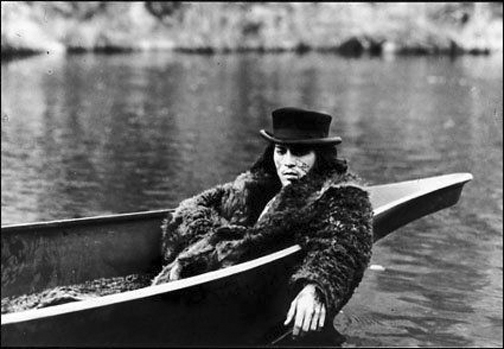

The two men now undertake an odyssey, pursued by the killers, in search of Blake’s ultimate destiny, which is revealed as a pleasing cross between the mysticism of the original Blake and the American Indians.

“Dead Man” is a strange, slow, unrewarding movie that provides us with more time to think about its meaning than with meaning. The black and white photography by Robby Muller is a series of monochromes in which the brave new land of the West already betrays a certain loneliness. Farmer brings to theIndian a sweetness and a curious contemporary air (he talks like a new age guru), and Depp is sad and lost as the opposite of Nobody — which is, I fear, Everyman. A mood might have developed here, had it not been for the unfortunate score by Neil Young, which for the film’s final 30 minutes sounds like nothing so much as a man repeatedly dropping his guitar.

Jim Jarmusch is trying to get at something here, and I don’t have a clue what it is. Are the machines of the East going to destroy the nature of the West? Is the white man doomed, and is the Indian his spiritual guide to the farther shore? Should you avoid any town that can’t use another accountant? Watching the film, I was reminded of the original William Blake’s visionary drawings and haunting poems. Leaving the theater, I came home and took down my Blake and spent a very pleasant half-hour. So the evening was not a loss.