I can just vaguely remember the Rosenberg case from the early 1950s; long-ago adult voices echo in my memory, saying “They gave away the secret of the atomic bomb to the Russians.” It is a large exaggeration to suggest that the Rosenbergs literally gave the Russians the bomb, but they were found guilty of giving them classified information and for that they were executed, in one of the most famous and painful cases in American legal history.

Thirty years have passed, many books have been written on the Rosenbergs, and even now a controversy rages over a new book that concludes that Julius Rosenberg was probably guilty of spying — although his wife’s involvement is less clear. The controversy has spilled over into considerations of “Daniel,” a new movie that would seem to be about the Rosenbergs and their children (what other historical figures could possibly have inspired it?), although the filmmakers claim it is not.

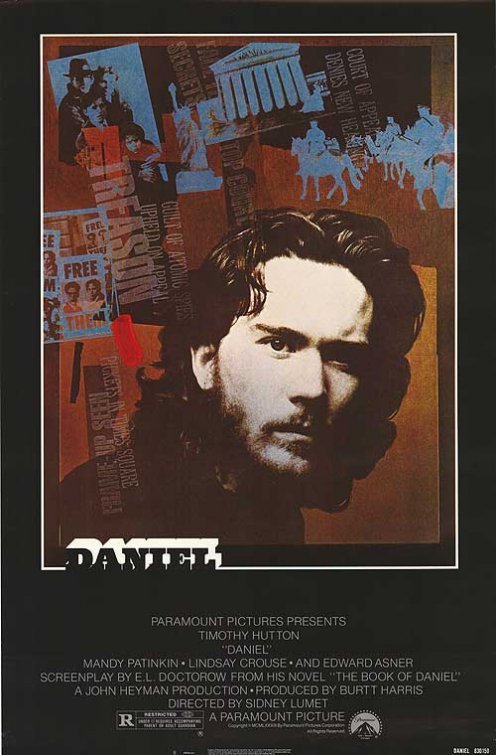

Sidney Lumet, who directed the movie, and E. L. Doctorow, who based the screenplay on his own novel, are at pains to separate themselves from the Rosenbergs — who are renamed the Isaacsons. Beyond the usual disclaimers, they say that their movie isn’t really about the parents, but about the legacy of the children.

As a viewer, I don’t really care. I don’t expect “Daniel” to be historically accurate about the original court case, nor do I want the story of the children to follow the real lives of the Rosenberg children. What I do want, though, is for the movie to make it clear where it stands on the Isaacsons. I don’t mean I want the movie to declare whether they were innocent of guilty — but whether they were good or bad. And there the movie holds back. The parents in this film are seen through such a series of filters — political, emotional, historical — that they are finally not seen at all.

The movie begins with a closeup of Daniel’s eyes. He is dispassionately reciting a dictionary entry about electrocution. These stark words summarize what happened to his parents and they are about the only knowable facts about the case. Then we meet other characters — Daniel’s sister, Susan, and the adoptive parents who took in the Isaacson children. Susan seems terribly scarred by her childhood; she is hysterical, angry, suicidal. Daniel is less visibly scarred, but he is brutally cruel to his young wife and we wonder if she represents, for him, the mother who left — who chose death over her children.

The movie then begins to move back and forth through time. There are warm sepia-toned flashbacks to left-wing days in the 1930s, when the Isaacsons are swept up in the euphoria of the American Communist Party. The present-day scenes, usually shot with lots of blues and greens, follow Daniel’s quest for friends of his parents who might share their secrets.

The frustrating thing about this approach is that the flashbacks — which presumably could contain the information Daniel desires — are noncommittal. They show how the Isaacsons behaved, but are never clear about exactly what it was they did, or didn’t do. It’s easy to assume that’s because the flashbacks are limited to what the children themselves witnessed. But, no, there are scenes in which the only people present are the parents (for example, a scene on a subway train where Jacob lectures Rochelle about Marx). Once the movie uses a single scene with an omniscient point of view, it becomes guilty of withholding additional information; if the film can see into the Isaacsons’ private moments when no children were present, then it can show us whether they passed secrets to the Russians.

But the film doesn’t want to. Its real subjects are the euphoric moments of left-wing idealism in the 1930s and how the passions of those moments are being paid for to this day by the children. Because the Isaacsons were swept up in a movement which gave them identity, support and a sense of participating in history, these poor, miserable kids have to pay the dues.

Now that would be a subject, if the kids were dealt with in depth. But the movie tries to encompass too much. It devotes so much time to the past, to the children’s childhoods, that the present-day scenes are slighted. Susan is clearly so disturbed that she’s of little help as a witness, but Daniel, the character the movie could have examined in three dimensions, is so manipulated by the plot that he remains a mystery. He’s always the detective, seeking out his parents’ friends, asking impassioned questions, functioning as the story device instead of as the subject.

At the end of “Daniel” we know that some emotionally careless parents left behind some emotionally crippled children. We suspect, oddly, that spy secrets and charges of subversion were not really relevant to the damage done to the children. I don’t think that was the movie’s intention.