The British are so very competent at getting everyone up in period costume and riding them around on horses that sometimes, as with “Cromwell,” they figure that’s enough. It isn’t anymore. The better historical films of recent years — “A Man for All Seasons,” “The Lion in Winter,” “Patton” — have worked themselves away from costumes and into the minds of their heroes. “Cromwell” is back in the tradition of great crowds rushing hither and yon in manufacture of obscure crises.

That’s despite the film’s energetic effort to make the issues clear. As nearly as possible in a movie that lasts three hours and covers maybe 10 years, “Cromwell” is faithful to the facts. We follow King Charles’ differences with Parliament, Cromwell’s differences with Charles and Parliament, everyone’s feelings about the divine right of kings, and Cromwell’s final seizure of power. We follow them all too well, but with little sense of the human beings involved.

I’ve argued as a general principle that it doesn’t matter if a movie is faithful to a book. What matters, is whether the movie is any good in its own right. I think I’d be willing to extend that argument even into the area of historical drama; if the movie works, I’m not concerned with its accuracy. I’d rather get a feel for the period and the characters, and see a director and actors in the act of invention. You can always check the dates at the library. So what if events get messed with a little? Didn’t Shakespeare do away with an entire decade in “Richard III” just so Richard could propose to Anne over her husband’s coffin? What we’re after, basically, is a good film and a sense of the people involved. “Cromwell” gives us neither.

Ken Hughes’ direction doesn’t seem adequate for the epic form. He doesn’t seem to have gotten on top of all the material. There are vast battle scenes, lots of extras, and any number of shots of castles on the horizon (with trumpets on the sound track). But he doesn’t bring the production into scale with his characters.

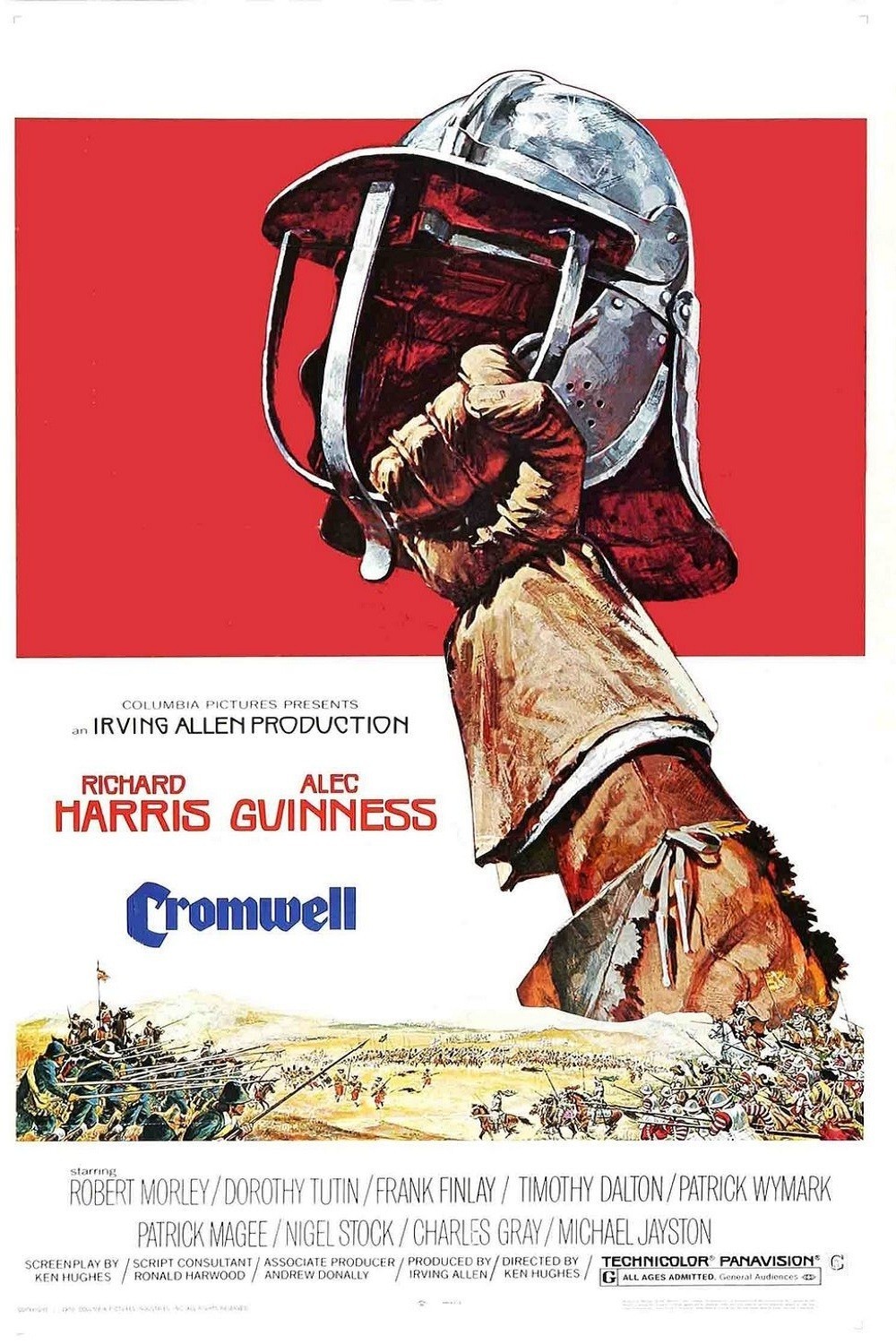

Richard Harris, as Cromwell, schleps around the kingdom reciting epigrams and looking distracted. He doesn’t inhabit the role or even seem to care much about it. Even worse is Alec Guinness, as King Charles, who is so concerned with doing a character turn that he doesn’t do a character. Both of them tend to fade into backgrounds — particularly since the cinematography in crowd and Parliament scenes keeps losing them.

The scenes in the House of Parliament, by the way, are particularly unhappy. One of the things you remember from “A Man for all Seasons,” whether you liked it or not, was that Parliament was a definite presence. The members seemed alert and involved and — there. “Cromwell’s” Parliament is a mob of extras, and not very well handled extras at that. They act like the mob in “Ryan's Daughter“: A herd of too-disciplined actors with knee-jerk yeas and nays. In “Cromwell,” Parliament changes its mind after almost every speech. Robert Morley says something, and Parliament cheers. Then Harris contradicts him, and Parliament cheers again. It needed Arthur Godfrey with his applause meter.

Footnote: The print I saw, at the Marina II, was projected very badly. One of the projectors wasn’t properly framed, and both were apparently running at slightly slow speeds, making the background music sound flat. Automated cinemas may not quite be here to stay.