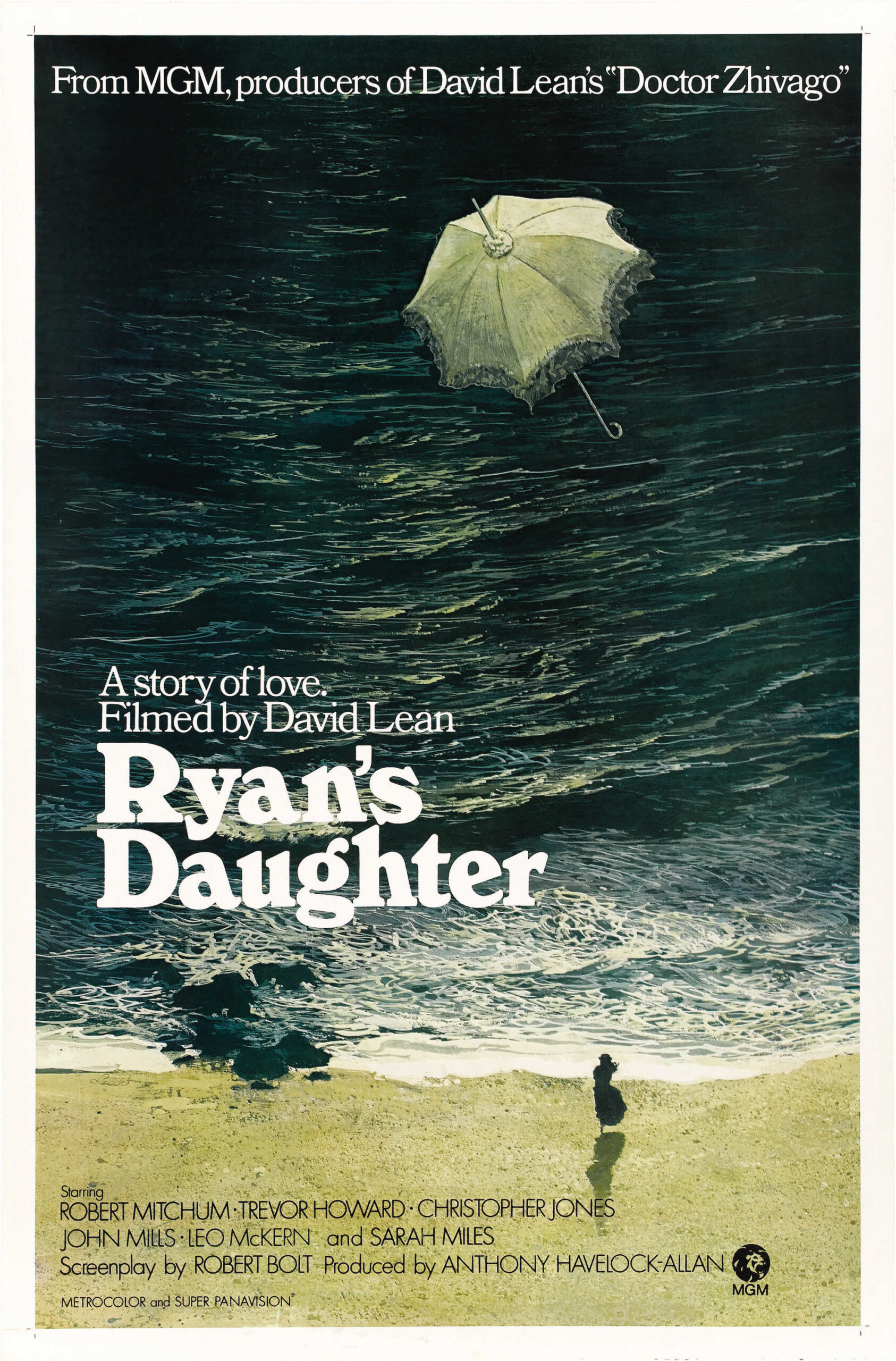

The very first shot of David Lean‘s “Ryan’s Daughter” shows us a tiny speck of a figure running along the ridge of an enormous cliff. Alas, this shot introduces the tone of the film all too well; Lean’s characters, well written and well acted, are finally dwarfed by his excessive scale.

Not every subject is suited to the epic treatment, to the vast landscapes and towering clouds and portentous musical scores, of the recent Lean style. “Dr. Zhivago” could support it because the Russian revolution was appropriate to the heroic scale. But a simple little love triangle on the Southwest coast of Ireland simply can’t bear the weight of Lean’s overachieving.

The distance between the subject and the style eventually proves fatal to “Ryan’s Daughter.” That, and a puzzling inability on Lean’s part to keep his symbols under control.

The night after Rosy Ryan and the handsome young officer first meet, for example, we get a shot of the officer’s stallion neighing and the girl’s mare perking up its ears. This sort of failure of tone is inexcusable and alerts us to worse lapses later on. When the young couple makes love for the first time, we’re hardly surprised when Lean shows the seeds blowing off a dandelion pod and landing, you guessed it, in a lake.

“Ryan’s Daughter” is an original screenplay by Robert Bolt, who also did Lean’s “Zhivago” and “Lawrence of Arabia.” With those two successes behind them, I wonder if Lean and Bolt weren’t simply trying to duplicate the formula instead of trying something new. “Zhivago” in particular was the story of a doomed love affair, played out against vast historical events. “Ryan’s Daughter” is a modest retread.

But with all due respect for the Irish, who knew how to stage a revolution with style, the IRA uprising was not quite on the scale of the Russian revolution, and Omar Sharif and Julie Christie, writ large against the steppes, overshadow a naive little publican’s daughter and a quiet school teacher. The problem with Ryan’s daughter isn’t that her epic love has been caught up in the tides of history, but that she has hot pants.

Her lover, if an early hint is to be believed, doesn’t even bother to tell her he’s already married. Her husband patiently waits for them to “bum it out.” The whole affair becomes pretty tawdry, and so when Lean pulls his camera back two miles and puts on the 1,000 mm lens, and the music swells heroically, and the heavens and earth seem to confer godlike stature on the couple, we can’t buy it.

While you’re watching “Ryan’s Daughter,” memories of “The Informer,” “Odd Man Out” and “The Quiet Man” keep stirring. We remember from those films, and from what else we know about the Irish, that they’re nothing like the carefully choreographed mobs of the Lean film. They’re a dour and cynical race sometimes, but they smile on occasion and they’re not all shrews and traitors.

Yet, in the Lean film the function of the village population is to run on cue to whatever’s happening. The people of the village all throng into the street, or they all race to the beach, or they all go inside and slam their doors, or they all go to persecute Rosy, all at once. Nobody in the movie except the stars goes anywhere by himself. Maybe the villagers are supposed to be a Greek chorus. I dunno. The effect wearies you after a while, anyway.

Besides, there’s already a Greek chorus in the film, in the form of John Mills. He plays a deformed village idiot, whose function is to miraculously eavesdrop on every supposedly private moment in the film. He then counterpoints the heroic characters on a comic scale, mocking the young officer and following him around. He is also the instrument for the betrayal of the adulterous affair, and he is the indirect cause of the officer’s death. Just as well. If there weren’t somebody to spill the beans, you have the feeling no one in the movie would catch on.

Against all of these failures, which I think must largely be charged to Lean, “Ryan’s Daughter” persists in giving us several scenes that work. There is an absolutely stunning storm sequence, for example, where quite authentic waves and winds pound against men who tie ropes around their waists and go into the surf after weapons for the IRA. By its very success, this scene demonstrates what’s wrong with the tone of most of the movie. The actions of the characters and the scale of the scene suit each other; there’s a reason for the men to be there, risking their lives. But Lean insists on the spectacular even in his trivial scenes.

The performances largely survive the film’s visual overkill. Robert Mitchum is splendid as the schoolteacher, and you realize once again what a fine actor he is. He’s the only American in the cast, and yet paradoxically he seems the most Irish. Trevor Howard gives a bravura performance as Father Hugh, and the two of them have a gem of a scene on the beach, one in his cassock, the other in his nightshirt.

Sarah Miles plays Rosy very well, and yet her accurate interpretation of the role helps once again to betray Lean’s excesses. Rosy is essentially a simple, inexperienced girl who has very dangerously confused sex and love. The more we see of her naivete, the more we can’t accept her great love as being made on Olympus. That’s also made difficult by Christopher Jones’ performance as the soldier. An actor could hardly express less without playing a corpse. You figure she must want him for his body; he never says a single tender, or beautiful, or revealing thing to her. All he wants to know is when he can see her next.

I have a friend who says a new David Lean movie is like a new Picasso. It may not be a great Picasso, he says, but by God it’s a Picasso and worth seeing for that reason if for no other. I suppose that’s true of Lean and all great directors: Their work is interesting just because they’ve signed it, and the failures help to illuminate the successes.

Maybe you should see “Ryan’s Daughter” for that reason. I imagine it will be around a long time and that it will find an enormous audience of those hungry for True Romances on the epic scale. For the rest of us, “Ryan’s Daughter” remains a disappointing failure of tone, a lush and overblown self-indulgence in which David Lean has given us a great deal less than meets the eye.