It was a time when the rich flirted with communists and fascists, when the poor stood in bread lines, when the class divide in America came closer to the boil than ever before or since. The 1930s were a decade when the Depression put millions out of work and government programs were started to create jobs. One of them was the Federal Theatre Project, which funded “free theater for the people” all over the country, but was suspected by U.S. Rep. Martin Dies of harboring left-wing influences. Since the last right-wing theater was in ancient Greece, his was a reasonable suspicion.

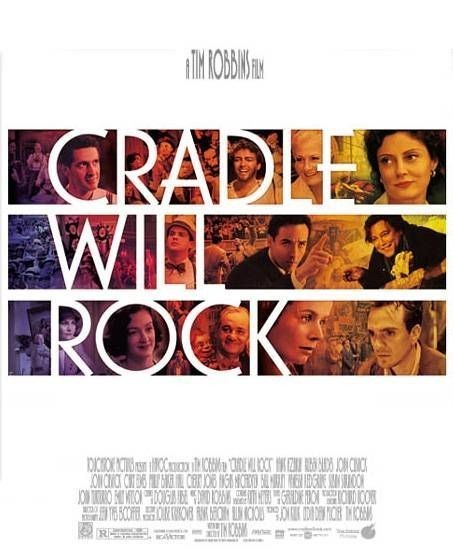

Tim Robbins‘ sweeping, ambitious film “Cradle Will Rock” is a chronicle of that time, knitting together stories and characters both real and fictional, in a way similar to John Dos Passos’ novel USA. It tells the story of the production of Marc Blitzstein’s class-conscious musical “The Cradle Will Rock”; its opening has been called the most extraordinary night in the history of American theater.

Intercut with that production are stories about Nelson Rockefeller (John Cusack), the millionaire’s son who partied with the Mexican communist painter Diego Rivera (Ruben Blades) and commissioned his mural for Rockefeller Center; and the newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst (John Carpenter) and fictional steel tycoon Gray Mathers (Philip Baker Hall), who bought Renaissance masterpieces secretly from Mussolini, helping to finance Italian fascism. We meet theatrical giants like Orson Welles (Angus Macfadyen) and John Houseman (Cary Elwes). And little people like the homeless Olive Stanton (Emily Watson), who eventually sang the opening song in “Cradle,” and Tommy Crickshaw (Bill Murray), a ventriloquist so conflicted that he helps a young clerk (Joan Cusack) rehearse her red-baiting testimony while his dummy sings “The Internationale,” apparently on its own.

There is a lot of material to cover here, and Robbins covers it in a way that will be fascinating to people who know the period–to whom names like Welles, Rockefeller, Hearst and Rivera mean something. For those who don’t have some notion of the background, the film may be confusing and some of its characters murky. It needs a study guide, and viewing “Citizen Kane” might be a good place to start.

The film’s anger is founded in the way Dies and his Congressional red-hunters brought the full wrath of the government down on poverty-stricken theater people whose new musical might be a little pink, while ignoring fat cats like Hearst, who not only bought paintings from Mussolini for bags full of cash, but whose newspapers published flattering stories about the dictator from his former mistress Margherita Sarfatti (played by Susan Sarandon).

Nelson Rockefeller’s flip-flops provide in some ways the best material in the film. Swept up in the heady art currents of the time, Rockefeller commissioned Rivera to paint a mural–and then, while the painter and his assistant were busy covering a huge wall of Rockefeller Center, was unhappy to learn the amorphous blobs hovering above portraits of the rich were molecules of syphilis and bubonic plague. The last straw was Rivera’s addition of a portrait of Lenin.

Rocky ordered the mural sledge-hammered to dust, and its destruction is intercut with the crisis in the “Cradle Will Rock” production (one syphilis molecule escapes the hammers and clings to the wall in defiance).

“Cradle Will Rock” was produced under the aegis of Welles and Houseman, whose Mercury Theater dominated radio drama, and whose “Citizen Kane” was only a few years in the future. Welles was a golden boy, only 21, flamboyant and cocky. When union actors declare a rest break during a rehearsal, he thunders, “You’re not actors! You’re smokers!” Then he limousines off to 21 for oysters and champagne. Welles comes across as an obnoxious and often drunken genius in a performance by Macfadyen that doesn’t look or sound much like the familiar original (ironically, Tim Robbins would make an ideal Welles).

Houseman is more admirable, especially after Federal Theatre funds are cut off and the Army padlocks the theater where “The Cradle Will Rock” is set to open. He and Welles lead a defiant march uptown to another theater, and when Actors’ Equity forbids its members to step foot onstage, composer Blitzstein (Hank Azaria) plays his score on a piano, and the cast members stand up in the audience to perform their roles.

The power of the Bliztstein play itself never really comes across in the film. It’s too fragmented, and its meaning seems less political than theatrical. It’s not what the play says that matters, so much as the fact that it was performed despite attempts to silence it. Its opening night was, in a way, an end of an era. Welles and Houseman soon went off to Hollywood and America went off to war, and it was 30 years before young Americans felt revolutionary again. Nelson Rockefeller went on to portray a “moderate” Republican, Hearst retired to San Simeon, and Rockefeller Center lost a tourist draw. Think how amusing the Lenin portrait would seem today, and imagine the tour guides pointing out the molecules of bubonic plague.