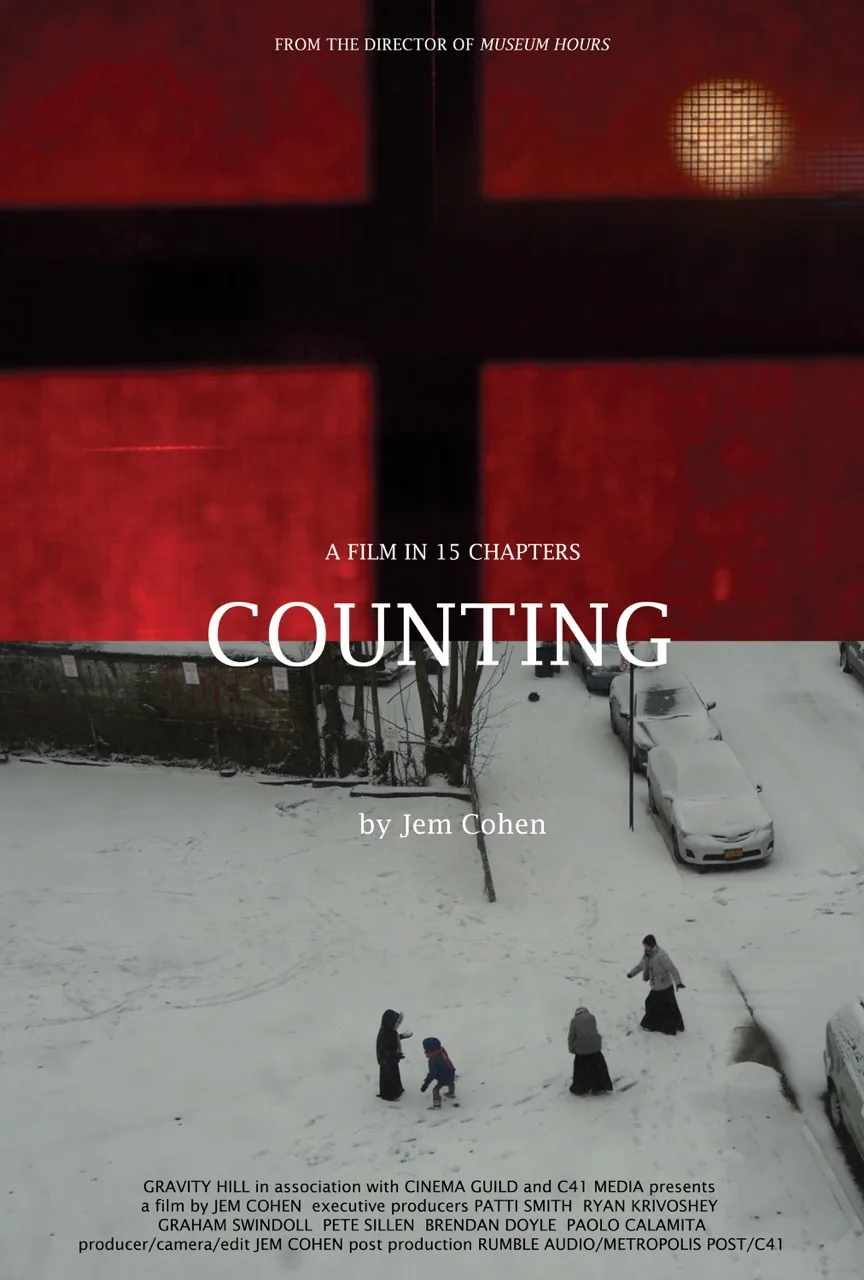

In his masterful “Museum Hours,” filmmaker Jem Cohen merged his skills as an urban documentarian with a narrative about two unlikely friends. Art, history, companionship, support and everyday life merged into one vision. His latest, “Counting,” billed as a “A film in 15 Chapters,” is both more ambitious and less purposeful in its intent. Clearly designed as a nod to Chris Marker (particularly “Sans Soleil”), “Counting” captures life around the world in all its simplicity and diversity, as Cohen bounces back and forth from New York City to Russia to Turkey, and locales in between. There’s little narration, little noise at all outside of the hum of traffic or the whine of a train or the rustle of leaves. Most people in frame are seen from behind, or via reflection, or from a distance. And there are cats. Everywhere. Cohen isn’t as interested in faces as he is urban tableaus. The result is a challenging work that can be both exhilarating and grueling in its deliberate pace. Cohen is an undeniably gifted filmmaker, even if the sum total of this piece isn’t quite as interesting as its parts.

“Counting” opens in New York City, featuring footage that the filmmaker captured around the city from 2012 to 2014. The first segment of “Counting,” which I believe is also its longest, is arguably its best as it’s a fantastic display of Cohen’s skills. He can turn the mundane imagery of urban existence into art by the way it’s shot, scored, or juxtaposed with another image. What captures his eye and the way he weaves into a piece can often result in great art. In the first segment, we hear a speech about discovering the secrets of the universe while we view a sedentary homeless person. We see a torn page with a headline about “The World’s Last Mysteries.” Cohen is placing imagery and audio of the questions of the universe against reflections of travelers on a train or a homeless man crossing the street. This is daily life and the world’s greatest mysteries are contained within it.

Cohen has a remarkable ability to go from placid, almost soothing imagery to kinetic, more frantic footage like when he captures an “I Can’t Breathe” protest scored to discordant, loud music. Even flags waving in the wind at a car dealership look antagonistic. He’s playing with the essence of filmmaking here, knowing that the images just before and after those flags, along with the choice of audio, change the way the viewer responds to them.

Sometimes Cohen can be straightforward and even didactic, such as in chapter 7, in which he presents imagery of reflections of people on their phones accompanied by audio of testimony about the NSA wiretapping. Although even this “short film within the big film” feels contextually resonant within a piece that feels, at least to me, about interconnectivity and commonality. Cohen jumps around the world and finds numerous images that look like reflections of each other. People crossing squares in New York City and St. Petersburg become often indistinguishable. Some of his compositions are picture-postcard beautiful while others take a minute to even discern what it is being displayed. And he’s obsessed with travel and motion. A voice sings in one chapter, “Do you ever wonder where it is you’re wandering?” We’re all wanderers around this world that’s more similar than we even know.

There are times, many times actually, when “Counting” feels a bit too self-indulgent, something that never struck me during “Museum Hours,” an undeniably more accessible piece for the average filmgoer. It starts to get a bit exhausting and unfocused. Unpacking “Counting” can be difficult, and it feels at times like it’s purposefully so, as if Cohen is challenging traditional expectations of film analysis, even ones as often abstract as his. But one cannot deny the ambition of “Counting,” a movie that travels the world, connecting it through the commonality of both everyday behavior and the universal language of cinema.

“Counting” ends almost peacefully, with images of calm and night. I was hoping for a bit more cumulative power, something to tie these chapters together, but I think Cohen purposefully avoids those kind of easy cinematic answers. Maybe these are just images, people and places around the world that he found interesting. Perhaps you will too. And sometimes life is as simple as that.