More people will die in the US from opioid overdoses in the United States while you are watching this film than have died from opioids in Switzerland in 15 years. That’s according to one of the experts in “Coming Clean,” a documentary about the staggering costs from the mishandling of addictive pharmaceuticals in the United States. In the first few minutes of the film, the death toll is compared to other kinds of disasters: like a 9/11 every three weeks, like a jumbo airliner crash every week, like a Super Bowl arena-full of people each year.

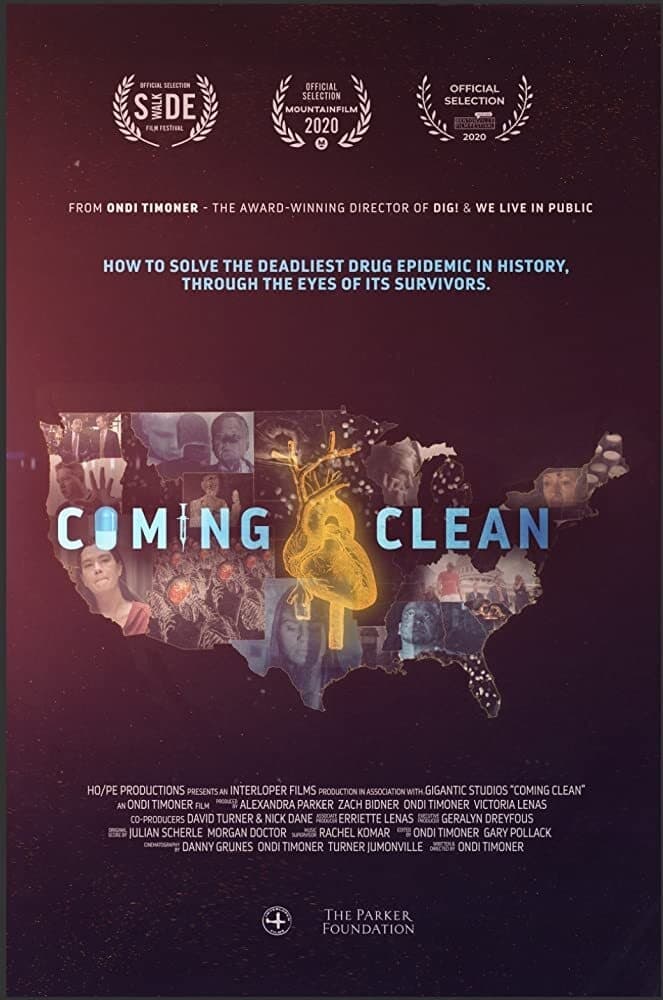

This is a big, complicated subject. Writer/director Ondi Timoner brings together a strong group that explores every aspect from the chemical to the cultural (drug abuse is seen as a crime when it is poor Black people and as a social or medical problem when it is middle- and upper-class white people) to governance (regulators and legislators swayed or thwarted by post-Citizens United dark money). We hear very briefly about the impact of categorizing pain as a vital sign, asking patients to select one from a line of emoticon-style faces ranging from peaceful to agonized, and about reimbursement to hospitals based on their success in pain management.

We also get a quick look at the problem of direct advertising of medication to consumers, which was restricted until 1997. It is fascinating to hear that one of the pioneers of that advertising is none other than psychiatrist-turned marketing whiz Arthur M. Sackler, whose eight relatives ran Perdue Pharma, developer of opioid-based pain medication. The connection between the neurochemical impact of opioids and the psychological seductiveness of advertising and financial bonuses in creating this epidemic is clear. So is the connection between opioids and tobacco, both high-profit commercial products whose manufacturers hid their pernicious effects from the government and consumers. The same lawyer who got a $246 billion payment from the tobacco companies, Mike Moore, is a striking figure in this film as he targets the pharma firms for his next big lawsuit. (There are also significant lawsuits brought by large shareholders.)

Each of these elements could more than fill an entire movie. Excellent films like “The House I Live In” and “The Definition of Insanity” have focused on the failures and inadequacy of the criminal justice system to deal with these issues and alternative programs that show encouraging signs of safer, cheaper, more humane, and more successful outcomes. In this film, some of the larger points are pushed to the side in favor of personal examples. One involves a 60-something white woman who says she had a comfortable and happy middle-class life until she fell and hurt her back. She was prescribed opioids and became an addict. Like many others, she then turned to heroin, often cheaper and easier to get than prescription drugs.

We also see a young Colorado state legislator named Brittany Pettersen at a hearing on opioids. But we do not find out until further into the film that there is a connection between these two women. The addict is the legislator’s mother. This example hits home, literally. Even with all of her contacts as a politician, Pettersen found that only ten percent of those seeing help for addiction have access to the programs they need. So Pettersen helped to make Colorado the first state to adopt a group of major legislative initiatives to address addiction. She and her warm-hearted and supportive husband, Ian Silveri, are among the movie’s highlights.

Admiral James Winnefeld, Jr., who served under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, tells us about his son Jonathan, who died from an overdose at age 19 in his first week of college. The admiral and his wife have started a non-profit called The SAFE Project that works with educators, health care professionals, legislators, along with school, workplace, and veterans’ groups to address opioid addiction.

One of the documentary’s most compelling figures is Salt Lake City Mayor (later Congressman) Ben McAdams, who helped set up Operation Rio Grande, a diversion program that helps addicts detox and develop life skills. The program’s first graduates include a woman named Destiny Garcia. To demonstrate that being a part of the community and having a job is the best way to keep people from returning to drugs, the mayor hired her to work in his office, where she was happy, responsible, and so good at handling stressed out constituents she was promoted.

“Coming Clean” is about how we got here. It is also about why our response has been so counter-productive, in part because we blame addicts for a failure of will or morality, in part because the people who are profiting from opioids have been very effective at thwarting government oversight. It is also about people who are trying to do better, like the Swiss program of providing heroin AND support services to addicts, which has eliminated overdose deaths for 15 years. We see politicians, lawyers, and doctors trying to find a better way, and we see those struggling with recovery. But it is not just the addicts who need to come clean; it is those profiting from the current system. The most deadly addiction is not drugs; it is money.

Now playing in virtual cinemas. Find out more here.