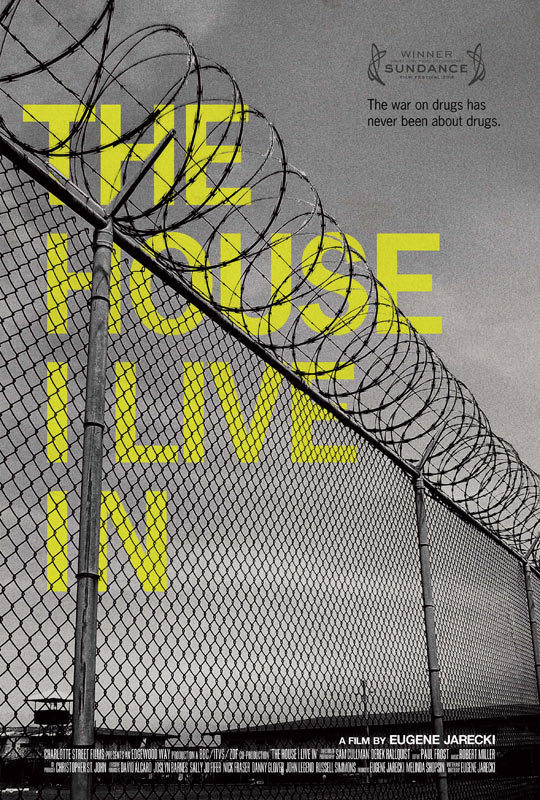

These thoughts occurred as I was watching “The House I Live In,” the documentary by Eugene Jarecki about our War on Drugs. Like other American wars, it has not been going so well. Its cost so far is more than $1 trillion dollars. Its effect on American drug consumption has been negligible. Its primary effect has been to assure a steady flow of non-violent, non-dealing drug users to our prisons, many of them for mandated sentences of five, 10, 20 or 40 years — or life. Hearing his sentence of 40 years for using crack, a young offender says flatly, “I messed up.” Let that be a lesson to him, although he may be dead by the time he can put it to use.

When I wrote, “young offender,” did you have a mental image of a black youth? Yes, 90 percent of those arrested for using crack are black, although only 13 percent of the nation’s crack users are black. Why is this so? Could it be that black men dealing crack on street corners are easy pickings for police patrols, but white offenders in affluent suburbs and Wall Street financial firms are not so easy to nab? The sad thing is that white crack users use poor blacks to run the risks for them.

Because of its disproportionate number of minority targets, the War on Drugs has been called a Silent Holocaust against blacks. The irony is compounded because so many prisons (many of them private, profit-making enterprises) are in lower-income white areas with a ready supply of low-salaried guards. The location of prisons is often due to the clout of white legislators.

But now the worm is turning, as Jarecki points out. Although pot and crack use results in mostly black arrests, low-income white areas are showing a dramatic growth in arrests for the manufacture and use of crystal meth.

No politician dares risk seeming soft on drugs, although the Obama administration did bring an end to sentences for crack (used more by blacks) that were sharply more extreme than powder cocaine (used more by whites). After all, it’s all cocaine.

Is drug abuse a victimless crime? Good question. Libertarians such as Ron Paul argue that what you put into your body is your business. It is the laws that produce victims — and they are the users themselves. Of course many victims result from crimes committed to get money to buy drugs. The libertarian argument is that if you decriminalize drugs, as some European countries have found, you remove the profit motive, and drug use falls. It has been said that the War on Drugs is essentially a price-support system for the drug cartels of Latin America.

Jarecki’s film makes a shattering case against the War on Drugs, using street footage, prison footage and the closer-to-home story of Nannie Jeter, the Jarecki family’s longtime housekeeper, whose own son was arrested. In poor, jobless neighborhoods, selling drugs is often the only “easy” way to make money. And poor, jobless dealers are easy prey for the police, most of whom realistically believe their efforts are making absolutely no difference.

If we were to expand the War on Drugs to reach into affluent neighborhoods, fashionable clubs, board rooms, movie studios and yacht harbors, how well do you think that would go over? The only rich people who get busted are in show business. If we see even one rich, white executive locked up for several years for smoking pot or inhaling cocaine, that’ll be the day.