If I were to judge this film solely on its visuals, it would get an unqualified rave, no questions asked. It’s only when I start to think about the story and the tone that my enthusiasm inches downward, because it’s done more as an exercise than as a narrative you’re meant to care about. Maybe the ultimate destination of “City of Lost Children” isn’t in movie theaters at all, but on one of those video wall panels like Bill Gates is installing in his new house; you’d see an amazing image every time you walked past, and occasionally you’d linger for as many more astonishing sights as you felt capable of absorbing.

The movie is an expensive, high-tech French production, using more special effects than any other French film in history, and it is appropriate that a lot of its look seems inspired by that Parisian visionary, Jules Verne. It takes place not so much in the future (or even in the dated but vivid “future” as seen by Verne) as in a sort of parallel time zone, where there are recognizable elements of our world, violently rearranged. The co-directors, Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, created a similar visual extravaganza in their first feature, “Delicatessen,” a 1991 fantasy about cannibalism.

The movie takes place mostly on an offshore rig inhabited by the terrible and tragic Krank (Daniel Emilfork). Krank is terrible because he is a monster, and he is a monster because he cannot dream, which makes him tragic. So he kidnaps children, to steal their dreams and feed off them. One of his victims is Denree (Joseph Lucien), a little boy who is almost more trouble than he is worth. Kidnapping him is a mistake because Denree’s adopted brother is One (Ron Perlman, from TV’s “Beauty and the Beast“), a strongman and sometime harpooner. One tracks his brother to the rig to save him.

In the way it populates this plot with grotesque and improbable characters, “City of Lost Children” can be called Felliniesque, I suppose, although Fellini never created a vision this dark or disturbing. Krank’s world includes a large number of children, kidnapped for their dreams, along with a brain that lives in a sort of fish tank, several cloned orphans who cannot figure which of them is the original, some very nasty insects, and Siamese twins who control the orphans for nefarious ends.

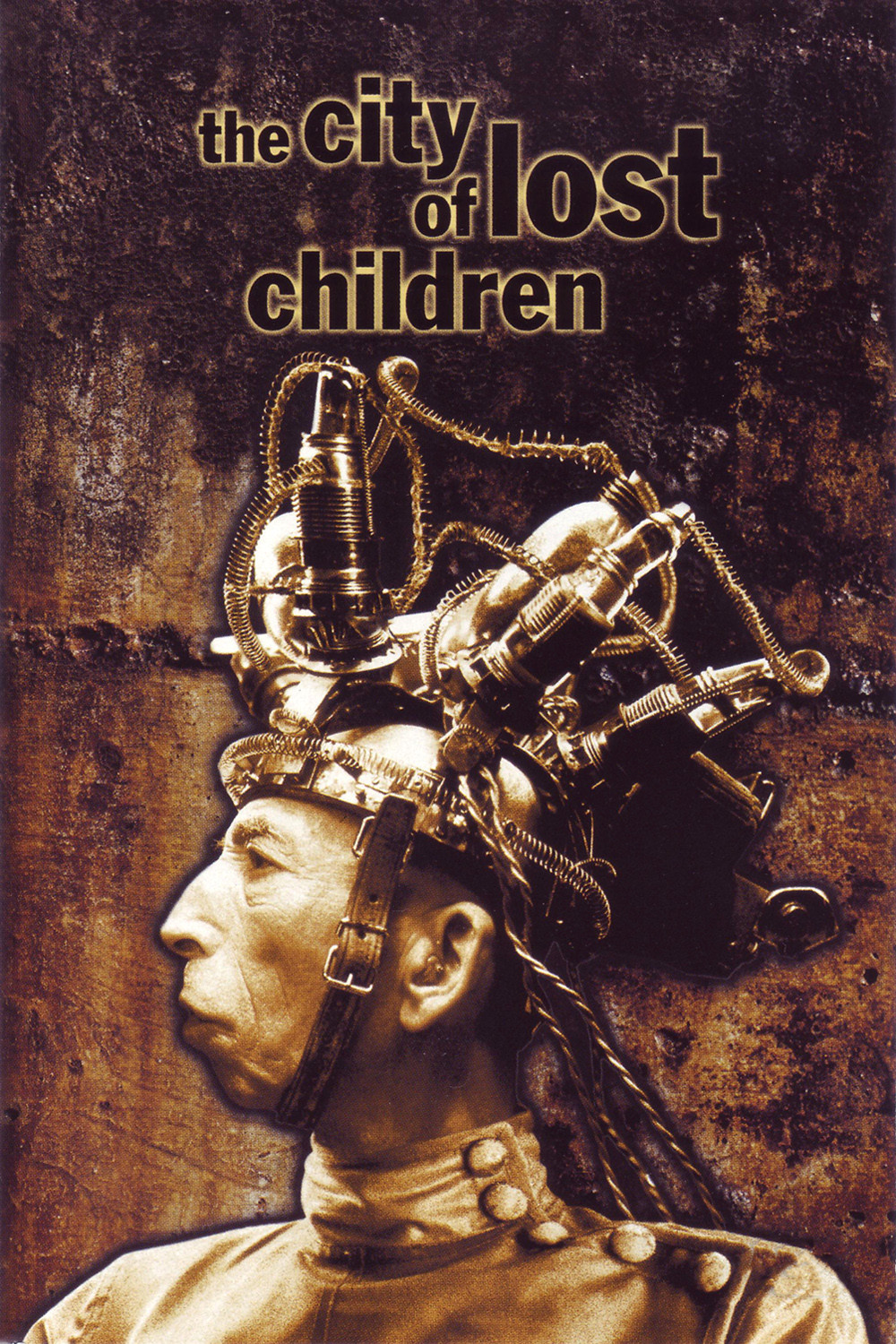

There are also deep-sea divers, performing fleas and some Cyclops men who have one eye removed and replaced with a computerized hearing device that allows them to visualize the sound waves of others. All of these people live in a universe constructed of much brass, wood, tubing, shadows and obscure but disturbing machines.

I would be lying if I said I understood the plot. Indeed, much of what I’ve just told you was reconstructed from the press kit and other sources. Watching the film, I perceived no strong narrative pull to carry me through, and instead was constantly being invited to stay in the moment, to experience one visual after another, to look past the characters and their concerns and relish the set design by Jean Rabasse and the bizarre costuming, in which Jean-Paul Gaultier has truly outdone himself, and that takes some doing.

When the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey” first came out, we lived in a more unabashed and experimental time, and as the movie played month after month, it began to attract nightly visits by hippies (for that was what we called certain types of young people in those far-off days, children). The movie had an intermission, during which the audience would file out onto the sidewalk for a smoke (never mind of what, children), and then file back in again. And the hippies, who had not bought tickets, would mingle with them and drift back into the theater, going right up to the front of the auditorium and lying on their backs to stare up at the screen.

Toward the end of the film there was a sequence where the space traveler was sucked into some kind of cosmic vortex of sound and light, and this is what the hippies had come to see. Although the screen was distorted from their strange point of view, that didn’t matter, because the visuals were overwhelming and, from so close, they felt consumed by them. “Far out,” they would mutter, along with other quaint phrases.

If “City of Lost Children” had been released then, the “2001” fans would have segued right across the street to take it in. Through the years there have been other such inspired films made for the eye: “Blade Runner,” “Fantasia,” “Days of Heaven,” “Brazil,” “El Topo,” “Santa Sangre,” “Akira” and indeed “Delicatessen” come to mind. I am trying to be rather precise here, because many people will probably not find themselves sympathetic to this movie’s overachieving technological pretensions, while others will find it the best film in months or years. You know who you are. I am not one of you. But I have enough of you in me to pass along the word. Far out.