Three shots into Rahmin Bahrani’s “Chop Shop,” and you’re already pulled into its world with an effortless economy and precision that leave you no doubt you’re in the best of cinematic hands.

As day laborers stand by the side of a busy road, we don’t see the road, but we can hear the traffic. Their heads turn as a truck pulls up off-camera, and they rush over to be chosen for work. The driver, speaking English, selects a few guys and tells a kid he doesn’t need him. Just as the truck pulls back out onto the highway, the kid hops into the pickup bed. He needs the work. Wherever this is, it’s a Third World economy.

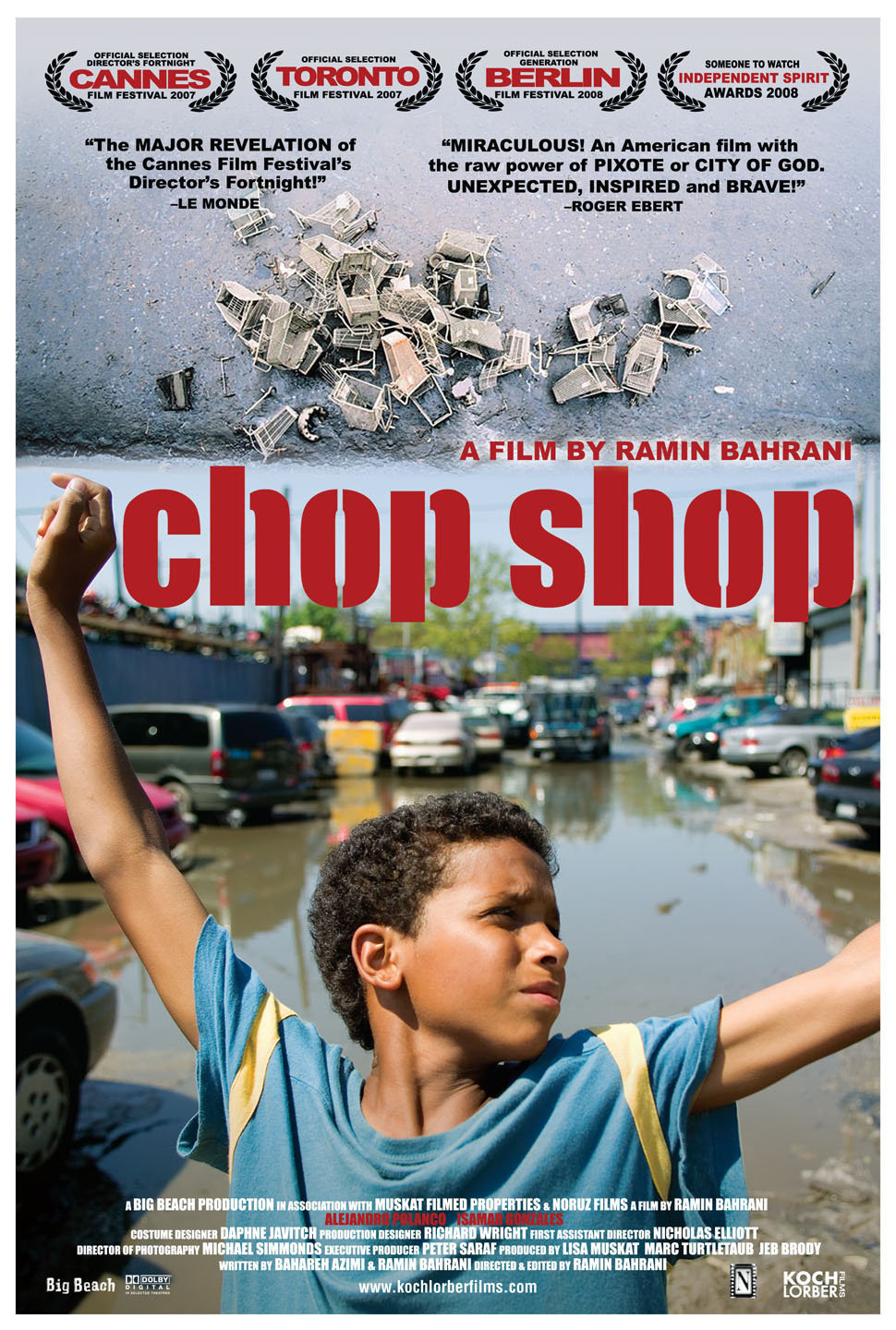

Second shot: The truck rolls past the camera, and we see the kid sitting up in the back. Third shot: The truck pulls over, and we notice the Chrysler Building, then the Empire State Building, in the distance. The driver gets out, lifts the protesting kid out of the back of the Chevy, gives the kid some money out of his own pocket and tells him to buy himself breakfast. Then the title of the movie appears.

Three shots in two minutes and we know so much about this boy’s toughness and resilience, the industrial gray-market conditions to which he has adapted and — despite his confidence and self-reliance — his inescapable dependence on the adults around him. The 12-year-old Ale (Alejandro Polanco) is an accomplished hustler, whether reselling bags of candy on the subway with a polished sales pitch or stealing hubcaps.

He lives, with his 16-year-old sister Isamar (Isamar Gonzales), in a tiny plywood room inside an auto mechanic’s shop in a chaotic district known as Willets Point (a k a the Iron Triangle), bustling with similar unauthorized parts and body joints. That’s about as big as Ale’s world gets. Looking out over the expanse of corrugated tin roofs and mud puddles, mufflers and radial tires, you could be in Mumbai or Sao Paulo or Mexico City. But this is Queens, N.Y., U.S.A. — a neighborhood pressed right up against Shea Stadium. Elevated trains rumble by at the end of the block and airliners leaving LaGuardia roar overhead.

Ale survives in a world inside a world inside a world. We all live that way to some extent. The magic of “Chop Shop” is the way it takes us deep into this particular place and shows us the people who live there, how they make a living, how they pass the time, what they eat, what they wear, how they deal with one another. It could be the most exotic spot on the face of the globe, or a few blocks from where you live.

All that matters is that the place comes alive onscreen, bursting with colors and textures that seem to sharpen your senses. If this description reminds you of other movies about scrappy street kids — like Vittorio De Sica’s “Shoeshine,” Satyajit Ray’s “Pather Panchali” or Hector Babenco’s “Pixote” — it should. “Chop Shop” is worthy of that company.

The same was true of Bahrani’s incandescent “Man Push Cart” (2006), about a Manhattan street vendor, which inspired critics to invoke comparisons to Italian Neo-Realism and cinema verite. But while those labels help place the films in a historical and stylistic context, they don’t do justice to the specificity and vividness — the bristling aliveness — that Bahrani, his actors and his superb cinematographer, Michael Simmonds, bring to the movie.

Yet for all the brilliance on display, there’s nothing ostentatious about its artistry. Everything about “Chop Shop” feels natural and effortless. Ahmad Razvi, the lead in “Man Push Cart,” appears in a smaller role here, and further demonstrates that he’s got star charisma, whether he’s playing a former Pakistani pop idol who runs a pushcart or a garage owner.

Two things American movies hardly ever get right are children and work. “Chop Shop” exhibits a rare and intimate acquaintanceship with both. Bahrani lingers on the labor of sweeping up the debris of the day, or buffing a nicked and scratched hood (the details of detailing, you might say). And he spends time with Ale when he’s working, and when he’s not doing much of anything at all — like, say, doing some pull-ups and nuking some popcorn in his room (“There’s a bed, a microwave and a fridge!” he boasts.

In only 84 minutes, “Chop Shop” makes you feel you’ve been somewhere you may never have known existed — even if you’ve flown over it, or taken the subway through it, or sat in a nosebleed seat at Shea. As in “Man Push Cart,” Bahrani knows precisely how and when to strike the final note and leave it reverberating in the air. It’s neither upbeat nor downbeat, just right. And it sends you soaring.