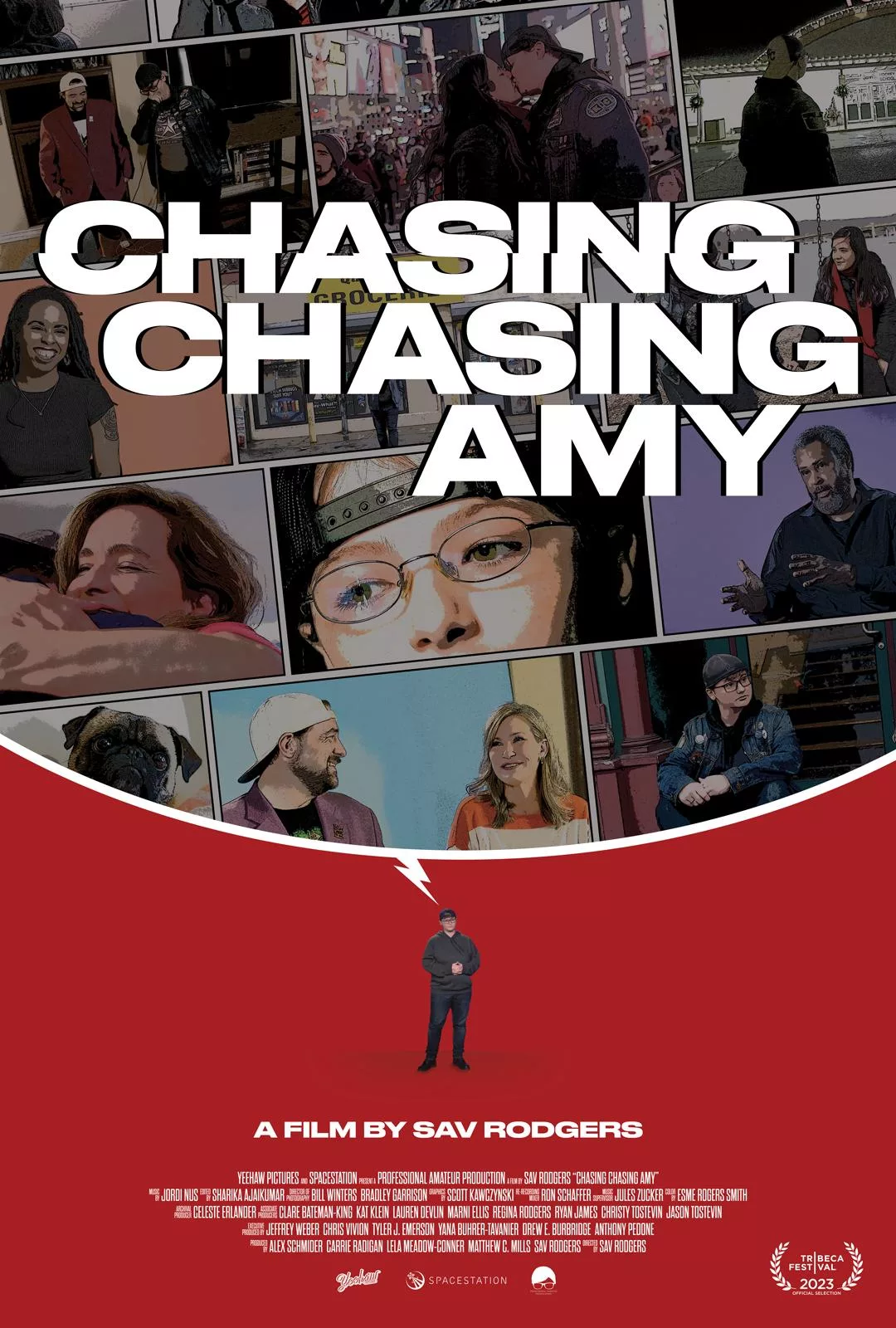

Kevin Smith is oft quoted as saying, “Every movie is someone’s favorite movie.” For young independent filmmaker Sav Rodgers, that movie is Smith’s own “Chasing Amy,” his talky, provocative 1997 feature about a heterosexual comic book artist (Ben Affleck) and the tragic romance he strikes with self-professed lesbian Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams). The film, celebrated in its time as a boundary-breaking indie darling (it’s even in the Criterion Collection), has now been reevaluated as time, culture, and queer politics have caught up with it. But for Rodgers, a young queer kid growing up bullied and alone in Kansas, his mother’s DVD of the film practically saved his life. Now, his fanaticism has fueled his debut doc, “Chasing Chasing Amy,” which starts as another in a long line of disposable auto-docs from people desperate to lend their pop culture darlings greater cultural significance before becoming something a bit more complicated in its back half.

“Amy,” like so many works before it, has endured quite the cultural revolution in recent years, and that’s where a lot of Rodgers’ focus lies in “Chasing Chasing”‘s opening act. There’s the standard montage of talking heads from people involved in the film (producer Scott Mosier, actor/fellow indie filmmaker Guinevere Turner) and cultural critics discussing from a modern context (Princess Weekes, Chris Gore), all musing on the film’s “problematic” nature. Here, we get insight into everything from Smith’s exalted place in the indie movie sphere of the ’90s to the shaky ways it reinforces (or, depending on how you look at it, gives voice to) biphobia and bi erasure.

Is it an issue that “Amy” is written from the perspective of a cis white male director, when even its blinkered understanding of queerness is a) baked into the psychology of Affleck’s flawed protagonist and b) still meaningful to queer audiences who absorbed it at the time? Rodgers’ perspective is that, no, it’s not; after all, he waxed rhapsodic about the film’s role in helping him come to terms with his own sexuality and gender identity in a TED talk that would eventually draw the eye of Smith himself. (The man would become an erstwhile mentor to the starry-eyed filmmaker—Smith, it seems, clearly adores having such an ardent fan still paying attention to his works).

“Chasing Chasing Amy” bounces between this broader examination of “Amy”‘s place in the indie film and queer theory spheres and Sav’s own relationship to it, and it’s the latter that proves more interesting. In many ways, it feels like Rodgers is using the opportunity of this doc to insinuate himself in the story of his favorite movie: striking up an erstwhile friendship with Smith, traveling to the film’s many locations and reenacting them with his girlfriend, Riley (whose story, blissfully, doesn’t seem to end as tragically as Holden and Alyssa’s). The film’s broader place in queer film history—kind of the straight guy’s answer to Turner’s “Go Fish” or Cheryl Dunye’s “The Watermelon Woman”—doesn’t matter quite as much as its place in Sav’s heart.

If the film resorted to uncritical hagiography, it’d be tempting to write off “Chasing Chasing Amy” as little more than a fan-appreciation letter in cinematic form. But the deeper Rodgers dives into the making of “Amy” and the parasocial relationship he begins to build with Smith and co., his investigation hits some snags that add an asterisk to his undying love for the formative picture. There is, of course, the Harvey Weinstein factor, with Smith confronting the fact that the very man who made his career was, at the time of “Amy”‘s Sundance premiere, sexually assaulting Rose McGowan in a hotel room at that same festival. The real barbs come out when Rodgers finally invites Adams herself—whose abortive relationship with Smith partially fueled the script—for an interview. Rather than the all-smiles retrospective we’ve had thus far, Adams confides in Rodgers a very different experience, both of the film itself and of her relationship with Smith at the time.

It’s an instructive moment, both for Rodgers and the audience: the young filmmaker, then in his twenties, must suddenly reconcile his formative adoration for the film with the thorny backstory that produced it. Tragically, Rodgers seems a bit too shaken and inexperienced to reckon with it fully on screen, and those moments are left hanging when they could use more introspection. (Instead, Rodgers leans on the autobiographical for the final act, which is sweet but loses the script on his focus on “Amy.”) Still, in their absence, such choices invite us to ask who a film truly belongs to. Is it the flawed artists whose blinders both shape and hinder the film’s voice? Or is it the audience, who can brush aside any ugliness of its making and glean from it what meaning they decide?

There’s a lot unexplored about fandom, queerness, and the ’90s indie movie scene in “Chasing Chasing Amy,” focused as it is on one filmmaker’s adoration of the subject at hand. But what’s left out of “Chasing”—and what the filmmaker decides to do, or not do, when faced with moments of clarity—can inform our own relationships with the art we love. It’s just a shame that, in the wake of Sav’s fan-bubble bursting, we don’t dig deeper to see what remains.