Three second-graders were brutally murdered on May 5, 1993, in West Memphis, Ark., and three young men are still in prison for the crimes, convicted in a climate that stereotyped them as members of a satanic cult.

The possibility that they are innocent gnaws at anyone who has seen “Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills.” That 1996 documentary argued that they were innocent and implied that the father of one of the victims might have been involved. He even supplied a knife to the filmmakers that seemed to match the profile of the murder weapon, but DNA tests on bloodstains were botched.

When “Paradise Lost” played on HBO, the film inspired a national movement to free the prisoners–Damien Echols, now 24, under sentence of death, and Jessie Misskelley, 23, and Jason Baldwin, 21, serving life sentences. Now comes “Paradise Lost 2: Revelations,” a sequel that involves their appeals, and also features extraordinary footage of Mark Byers, the father under suspicion, whose wife has died under mysterious circumstances.

The new documentary, directed like the first by Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky, premieres at 9 tonight on HBO. There is unlikely to be anything else on TV this week, or this month, more disturbing than this film. Watching it, you feel like an eyewitness to injustice.

Among new evidence introduced on appeal is the finding that human bite marks, found on one of the children’s bodies, do not match the bites of the three defendants. The film points out that Mark Byers had all his teeth extracted in 1997, four years after the murders, although on camera he places the extraction much earlier and gives several contradictory reasons for it.

What does this prove? Not much to prosecution forensic experts, who testify the bite marks were caused by a belt buckle.

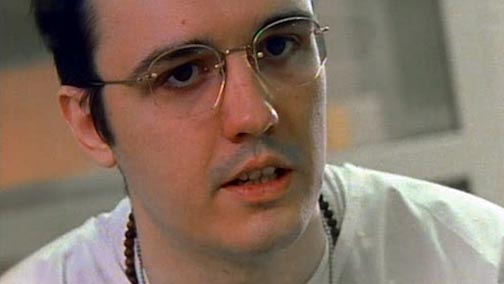

Byers spends a lot of time on camera (he accepted an honorarium for appearing in this film). He is described by Echols as “the fakest creature to ever walk on two legs,” and that seems the simple truth: He has an odd way of speaking in rehearsed sound bites, avoiding eye contact while using lurid prose that sounds strikingly insincere. Visiting the murder scene, he stages a mock burial and cremation of the three defendants, saying “there’s your head marker, you animal,” and then pouring on charcoal lighter, chortling “now we’re gonna have some fun,” and lighting his cigar before dropping the match.

Did he do it? We hear a litany of his problems: a brain tumor, manic depression, bad checks, drug abuse, DUIs, hallucinations, blackouts, neighbors who got a restraining order after he spanked their child, and the death of his wife. Byers rants about those who accused him of her death and says she died in her sleep of natural causes. Later, possibly in a Freudian slip, he says, “After my wife was murdered.”

The legal establishment in West Memphis seems wedded to its shaky case–dug in too deep to reconsider. Echols’ new attorney claims the original defense was underfunded and incompetent, and indeed we find that one attorney was paid only $19 an hour, and the defense was limited to $1,000 for tests and research in a case dripping with forensic evidence.

Questions remain. If the victims were killed in the wooded area where they were found, why was there no blood at the scene? Can a confession by Misskelley be trusted? He has an IQ of 72, was questioned by police for 12 hours without a parent or attorney present, and then was tape-recorded only long enough to recite a statement he later retracted.

On June 17, the appeal was turned down, by the same judge who officiated at the original trial. A federal habeas corpus motion is the defendants’ last chance.

Near the end of the film, Byers takes a lie detector test and passes. The film notes that at the time he was on five mood-altering medications. The last shots show him singing “Amazing Grace,” very badly.