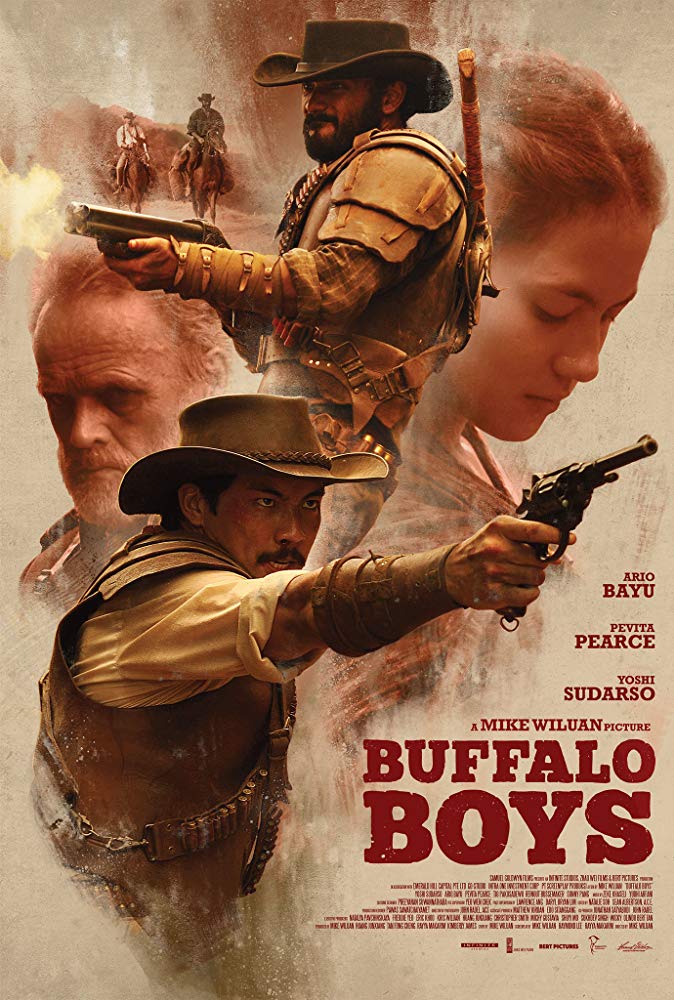

“Buffalo Boys,” an Indonesian action movie hybrid, is essentially made up of two different movies that barely go together: a thrilling martial arts film and a lurid revisionist Western. The plot is pretty standard for an action film: sometime in 1860, Indonesian brothers Jamar (Ario Bayu) and Suwo (Yoshi Sudarso) return to Java and avenge the death of their father, kind-hearted Sultan Hamza (Mike Lucock). There doesn’t need to be more to “Buffalo Boys,” but there is, as an introductory title crawl teases. We are told that “accounts of suppression, brutality, and tragedy are often lost in tales of folklore. This is one story where the world of facts and fiction collide.” That foreword over-promises what writer/director Mike Wiluan and his co-writer Raymond Lee eventually deliver. Because for the most part, “Buffalo Boys” is a decent folk tale, despite Lee and Wiluan’s periodic application of “Game of Thrones”-style sensationalism.

Wiluan and Lee are, for the most part, content to populate “Buffalo Boys” with familiar characters. For starters: Jamar and Suwo are the kind of siblings that you only meet in action movies. They have a moral code, as we see when they return to Java and spend most of their time deciding which bad guys to beat up. But they’re also young and wild, like when they–aided by their good-natured uncle Arana (Tio Pakusadewo)–operate and participate in bare-knuckle brawling competitions on an undisclosed California train. Women want to be with Jamar and Suwo, especially the ones who laugh appreciatively at the brothers after they unwittingly bathe in a popular freshwater spring. And men predictably want to be like Jamar and Suwo: the slimy highwayman and political opportunist Fakar (Alex Abbad) may never tell Jamar and Suwo that “You and me, we’re not so different.” But it’s basically implied.

Jamar and Suwo’s quest is also as pure-hearted as it is archetypal: Arana reluctantly sets his nephew on a path that leads them to confront evil Dutch Captain Van Trach (Reinout Bussemaker), a local despot who’s responsible for killing Hamza and banishing Arana. Fate–and some bad luck on the railway brawling circuit–may take a little time to pit Jamar and Suwo against Van Trach and his platoon of leering, bloodthirsty heavies. But–as genre-savvy moviegoers know–a bloody confrontation is inevitable, no matter what Wiluan and Lee’s prologue suggests.

Unfortunately, while the film’s preface is a bit overblown, it does effectively warn viewers about impending (and periodic) eruptions of brutal violence. Female protagonists are often verbally or physically threatened with rape and one is even flogged with a whip until her back is scored with bloody wounds. And almost all male characters, good or bad, either dispatch or are dispatched with a fair amount of gore and some thunderous sound effects. There’s even a “Game of Thrones”-like hanging, one that distractingly resembles the death of a major character at the end of the HBO drama’s first season (as well as the conclusion of the first book in the “A Song of Fire and Ice” series). None of these scenes seem to matter as they’re all rushed through without many noteworthy or novel details. These grisly scenes also appear to hail from a completely different film than the rest of “Buffalo Boys.”

Which is a real shame since the film’s action scenes are mostly decent. Wiluan often centers his camera on his performers, either panning from side to side or confronting his characters as they (facing towards but not directly at the camera) threaten their off-screen opponents. Better yet: the action choreography (directed by Kazu Patrick Tang and coordinated by Top) is complimented by rhythmically paced edits that give the fight scenes a sense of urgency to match their visual dynamism. The worst thing that I can say about these action scenes–which are the real reason you should watch “Buffalo Boys”–is that there aren’t enough of them. The introductory fight–set on a train, of course–is, realistically, the film’s highlight.

<span class="s1" Thankfully, there are a handful of other strong set pieces in “Buffalo Boys,” including the film’s splashy climactic fight. I’m not sure that there are enough such moments to warrant more than a heavily qualified recommendation. But while “Buffalo Boys” may not be everything it could have been, it is sometimes good enough.