Steven Soderbergh’s “Bubble” approaches with awe and caution the rhythms of ordinary life itself. He tells the stories of three Ohio factory workers who have been cornered by life. They work two low-paying jobs, they dream of getting a few bucks ahead, they eat fast food without noticing it, two of them live with their parents, one of them has a car. Their speech is such a monotone of commonplaces that we have to guess about how they really feel, and sometimes, we suspect, so do they.

I haven’t made the movie sound enthralling. But it is. The characters are so closely observed and played with such exacting accuracy and conviction that “Bubble” becomes quietly, inexorably, hypnotic. Soderbergh never underlines, never points, never uses music to suggest emotion, never shows the characters thinking ahead, watches appalled as small shifts in orderly lives lead to a murder.

Everything about the film — its casting, its filming, its release — is daring and innovative. Soderbergh, the poster boy of the Sundance generation (for “sex, lies, and videotape” 17 years ago) has moved confidently ever since between commercial projects (“Ocean's Eleven“) and cutting-edge experiments like “Bubble.” The movie was cast with local people who were not actors. They participated in the creation of their dialogue. Their own homes were used as sets. The film was shot quickly in HD video.

And when it opens in theaters, it will simultaneously play on HDNet cable, and four days later be released on DVD. Here is an experiment to see if there is a way to bring a small art film to a larger audience; most films like this would play in a handful of big-city art houses, and you’d read this review and maybe reflect that it sounded interesting, and then lose track of it. In a time when audiences are pounded into theaters with multimillion dollar ad campaigns, here’s a small film with a big idea behind it.

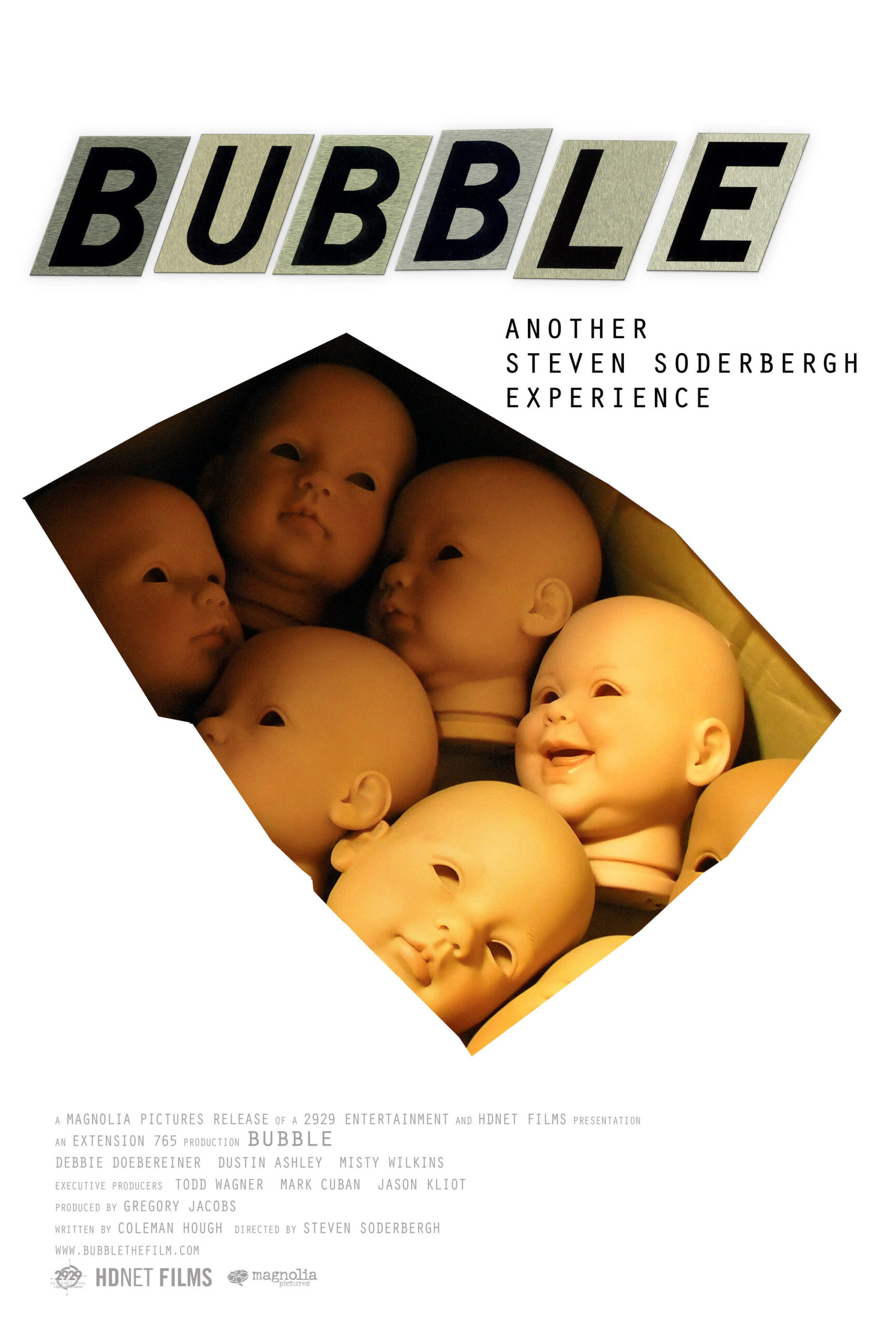

As the film opens, Martha (Debbie Doebereiner) awakens, brings breakfast to her elderly father, picks up Kyle (Dustin Ashley) at his mobile home, stops at a bakery, and arrives at the doll factory where they both work. He operates machinery to create plastic body parts. She paints the faces and adds the eyelashes and hair. During their lunch hour in a room of Formica and fluorescence, they talk about nothing much. He doesn’t have time to date. He’d like to get the money together to buy a car. He’d like a ride after work to his other job. Martha, who is fat and 10 or 15 years older than Kyle, watches him carefully, looking for clues in his shy and inward speech.

Rose (Misty Dawn Wilkins) begins work at the factory. She is introduced to the work force and provides Kyle with a smile so small he may not even see it, but Martha does. How should we read this? In a conventional movie, Kyle would be attracted to Rose, and Martha would be jealous. But “Bubble” is more cautiously modulated. Martha, I believe, has never allowed herself to think Kyle would be attracted to her. What she wants from him is what she already has: A form of possession, in the way he depends on her for rides and chats with her at lunch. Nor does Kyle seem prepared to go after Rose. He is shy, quiet, withdrawn, smokes pot at home, keeps a low profile at work.

Rose at least represents change. She takes Martha along to a suburban house that she cleans, and Martha is shocked to find her taking a bubble bath. Rose explains that her apartment, which she shares with her 2-year-old daughter, only has a shower. “I’m not too sure about her,” Martha tells Kyle. “She scares me a little.”

Rose asks Kyle out. In a bar, they share their reasons for dropping out of high school. Their date goes nowhere — not even when Rose gets herself asked into his bedroom — because Kyle is too passive to make a move, or maybe even to respond to one. He’s too beaten down by life. “I’m very ready to get out of this area,” says Rose, who observes that everybody is poor and there are no opportunities.

I am describing the events but not the fascination they create. The uncanny effect comes in large part from the actors. I learn that Debbie Doebereiner is the manager of a KFC. That Misty Dawn Wilkins is a hair dresser, and her own daughter plays her daughter in the movie. They are not playing themselves, but they are playing people they know from the inside out, and although Soderbergh must have worked closely with them, his most important work was in the casting: Not everybody could carry a feature film made of everyday life and make it work, but these three do. The movie feels so real a hush falls upon the audience, and we are made aware of how much artifice there is conventional acting. You wouldn’t want to spend the rest of your life watching movies like this, because artifice has its uses, but in this film, with these actors, something mysterious happens.

I said there was a murder. That’s all I’ll say about it. The local police inspector (Decker Moody) handles the case. He is played by an actual local police inspector. We have seen a hundred or a thousand movies where a cop visits the crime scene and later cross-examines people. There has never been one like this. In the flat, experienced, businesslike way he does his job, and in the way his instincts guide him past misleading evidence, the inspector depends not on crime-movie suspense but on implacable logic. “Bubble” ends not with the solution to a crime, but with the revelation of the depths of a lonely heart.

Some theater owners are boycotting “Bubble” because they hate the idea of a simultaneous release on cable and DVD. I think it’s the only hope for a movie like this. Let’s face it. Even though I call the film a masterpiece (and I do), my plot description has not set you afire with desire to see the film. Unless you admire Soderbergh or can guess what I’m saying about the performances, you’ll be there in line for “Annapolis” or “Nanny McPhee.” But maybe you’re curious enough to check it out on cable, or rent it on DVD, or put it in your Netflix queue. That’s how movies like this can have a chance. And how you can have a chance to see them.