If “Bright Young Things” were set today in Manhattan, it would be about Paris and Nicky Hilton and their circle, Rupert Murdoch, the gossip writers of Page Six, and bloggers for sites like defamer.com. That might make a good movie.

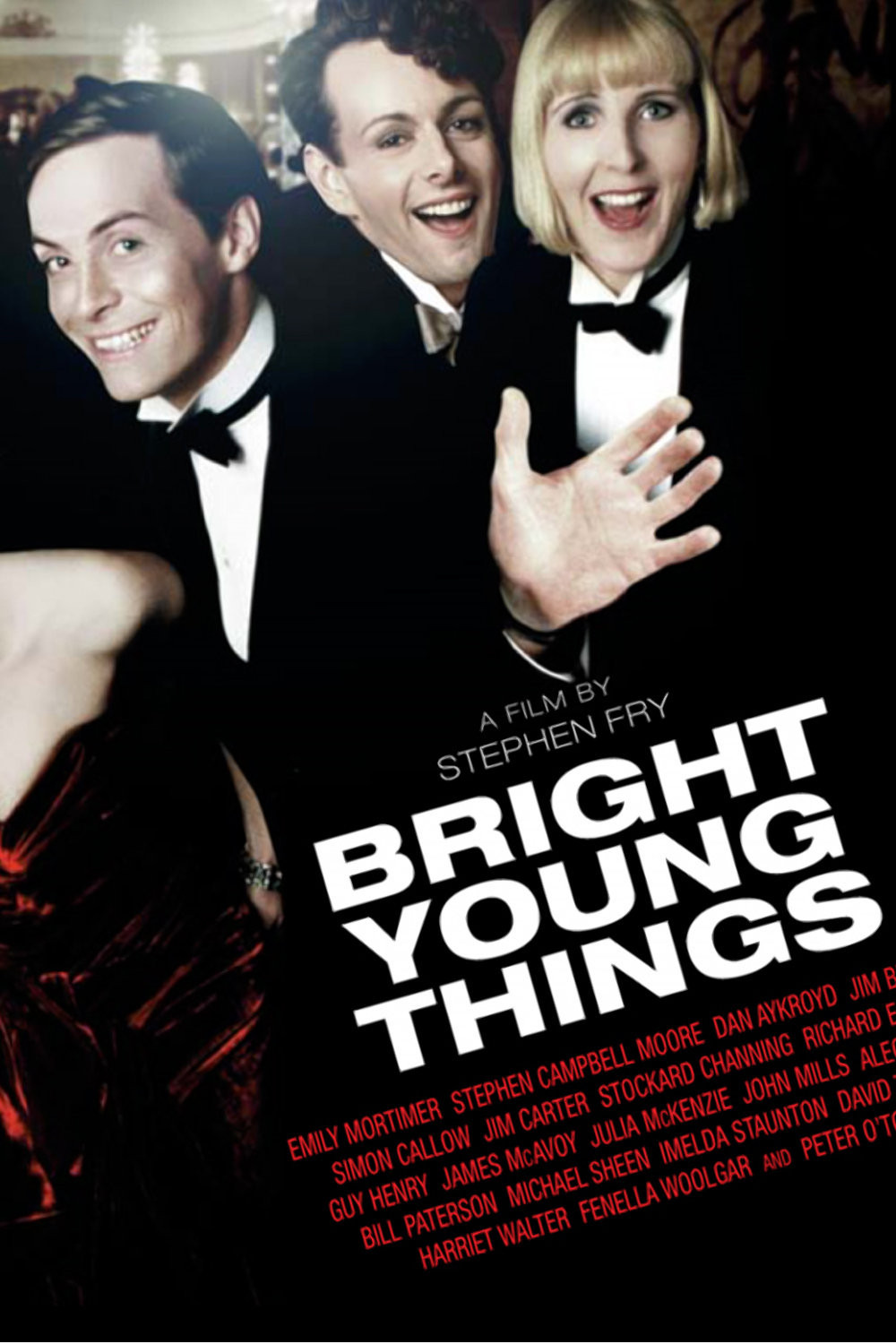

Certainly it would if it were done in the spirit of Stephen Fry’s new film, based on Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies (1930), which has been called the funniest English novel of the century. Five or six books by Wodehouse may outrank it, but never mind; what’s striking about the Fry version is how clearly he sees the underlying sadness. Until a few years ago he was a Bright Young Thing himself, and there may be elements of autobiography lurking here somewhere. “What a lot of parties!” one of the exhausted young things sighs late one night.

The story takes place in London and English country houses between the two wars, and, like Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time, occupies the intersection of the aristocratic, the rich, the ambitious, the decadent, the fraudulent and the bohemian. The most important requirement for BYT membership is never to be boring, although one can often be bored. Alcoholism is the recommended lifestyle.

The hero, as so often in comic novels, is an earnest young man who wants to get married but lacks the money. Adam Symes (Stephen Campbell Moore) has great hopes for his new novel, having already spent his publisher’s advance, and when his only manuscript is seized as pornography at customs, he is in despair. How can he marry the fragrant Nina (Emily Mortimer) without the money to support her in the style to which she wants to become accustomed? Nina loves him, truly she does, but she hates poverty more.

Adam moves in circles which spin more quickly after midnight, and is a friend of the titled but impoverished Lord Simon Balcairn (James McAvoy), who attends all the best parties and then, as Mr. Chatterbox, writes anonymous scandal about them for a popular newspaper. His publisher is Lord Monomark (Dan Aykroyd), a Canadian press baron who seems to combine the worst (and, it must be said, the best) qualities of Murdoch and Conrad Black, although Monomark is of course the original. Simon has a crisis when his friends discover his double-dealing, and he is uninvited to a crucial party; he implores his friend Adam to cover for him, Adam produces a sensational (if libelous) scoop, and Lord Monomark (who likes to print tonight and call the lawyers in the morning) gives him the Chatterbox column.

This provides Adam with the money to marry Nina, but of course he will lose and regain his stake several times during the film; Waugh’s novel, like so much of Wodehouse, is about characters who are realistic about romance but idealistic about money. Adam’s rival for the hand of Nina is Ginger Littlejohn (David Tennant), who has money but is boring. Too bad, but to be poor like Adam is boring, too, and if she has to choose, Nina would rather be bored in comfort.

These friends are like sparrows in the springtime, all landing on a branch, chattering deliriously, and then at an invisible signal fluttering off together to perch on another tree. They move from restaurants to clubs to private parties, from town to the country, often awakening hung-over to discover that their genitals have misbehaved during a spell of drunken inattention. The most desperate in their circle is the movie’s manic party animal Agatha Runcible (Fenella Woolgar). In a scene that transcends invention and moves into inspired lunacy, Agatha is invited back to spend the night at the house of a tipsy new girlfriend, blunders into the breakfast room in the morning, and as those around the table regard her with horror, reads in the morning paper about where she spent (and is still spending) the night.

Like The Great Gatsby, the works of Dawn Powell, Jay McInerney and all the other novels about heedless romance and debauchery, “Bright Young Things” is about people who think they can live forever, and discover that to live forever in the way they are living is not only impossible but would become exhausting and discouraging. Agatha is the poster girl for this discovery. Adam and Nina are luckier, redeemed by pluck and optimism, and, it must be admitted, their real love for each other (this despite Adam’s offer at one point to sell his share in her to Ginger for 100 pounds; later in the movie, after another setback, she asks bravely, “Oh, dear, have I been sold again?”).

Fry, who as a younger actor was the obvious choice to play Bertie Wooster’s butler Jeeves (and did), is also the obvious choice to direct this material. He has a feel for it; to spend a little time talking with him is to hear inherited echoes from characters just like those in the story. He supplies a roll-call of supporting actors who turn up just long enough to convince us entire movies could be made about their characters.

Among these are Peter O'Toole (who here, and in “Troy,” steals his scenes almost kindly from his fellow actors); he plays Nina’s decaying old pater, Lord Blount, who has a gift for saying what he thinks while not seeming to know what he’s saying.

Jim Broadbent pops up regularly as a perpetually drunken army officer who makes extravagant promises to Adam, gives him tips on race horses (“Indian Runner at 37 to 1”), promises him money, disappears for months at a time, seems likely to be a fraud, and always remembers what he said when he was loaded, even though that may be of no help to Adam. The only character who doesn’t really fit in is Mrs. Ape (Stockard Channing), a religious zealot whose appeal to bright young things is questionable, especially while she sings “Ain’t No Flies on the Lamb of God.”

As pure comedy, “Bright Young Things” would be funny up to a point, and then repetitive. Waugh’s novel and Fry’s movie wisely see that their characters live by spending their comic capital and ending up emotionally overdrawn. They begin by being awake when everyone else is asleep, and end by being asleep while everyone else is awake. The funniest person in a bar is rarely the happiest. The movie has a sweetness and tenderness for these characters, poor lambs, blissfully unaware that they’re about to be flattened by World War II.