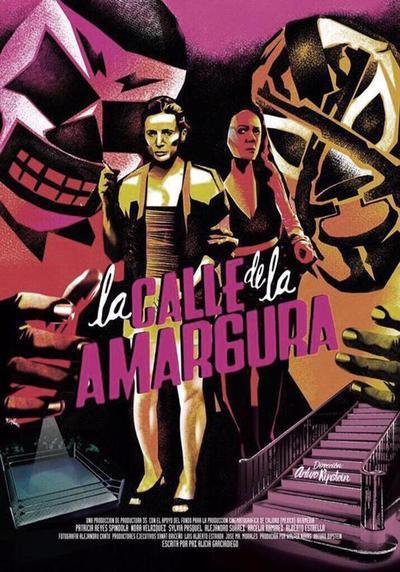

It is not often, unfortunately, that the work of the esteemed Mexican director Arturo Ripstein gets screened in the upper part of North America, outside of the festival circuit. The last film of his I was able to see was his 1999 adaptation of Gabriel García Márquez’s “No One Writes To The Colonel,” which I felt a misfire. There have been almost ten films between that one and “Bleak Street,” which begins a New York run on January 20. Written by Ripstein’s frequent collaborator (and wife) Paz Alicia Garciadiego, “Bleak Street” (“La calle de amargura”) is a visionary triumph for the 72-year-old director.

Shot in what appears to black-and-white digital video, “Bleak Street” conjures a contained labyrinthine hell in the alleyways and garages and tenement apartments in an impoverished section of Mexico City. Two sets of characters go about their quietly and oddly desperate lives. The first two are a pair of self-described “Lilliputian” masked wrestlers who are the “shadows” of two larger masked wrestlers. “Little Death” and “Little A-K” happen to be identical twins (we never see them without their masks, however), and they have splenetic tempers, wives and kids, drunken parents who ostensibly “manage” their careers, and a penchant for partying, despite the fact that one of them can’t quite get the scratch to get his costume act together—Big Death keeps riding his “shadow” about the lack of skeleton pattern on his wrestling gloves. Just around the corner are Dora (Nora Velázquez) and Adela (Patricia Reyes Spindola), two aging prostitutes with challenges of their own—in Dora’s case a spoiled, insolent daughter and a cross-dressing husband, in Adela’s case a lack of means that compels her to pimp out the even more aged woman with whom she shares an apartment. Not for prostitution, but for begging.

Hence the movie’s title, then. Ripstein depicts these squalid lives with a sometimes near-voyeuristic camera. Shots start off peering from behind iron gratings of staircases and so on. Despite being set in one of the world’s most crowded cities, the movie trades in a desolate sense of depopulation; the lobby of the hourly motel where Adela and Dora take two tricks as the film approaches its climax looks like an empty cavern, while the wrestling arena prior to the evening’s main event looks like it could be used as a stage by the woman in the radiator in “Eraserhead.” It’s this sense of surreality within a mode of social realism (the scenario, believe it or not, was actually inspired by true event) that gives the movie its off-kilter power.

Ripstein, who began his long career working with the maestro Luis Buñuel, has his one-time mentor’s post-idealistic anger but doesn’t adopt an insouciantly ironic mode to filter it through; his perspective is determined but never detached. He is served very well by the movie’s settings. The garage where Adela services her johns has “puta“ painted on the front iron gate, and is guarded over by the procuress Margara (Emoe de la Parra) who presides over the space from a wooden school chair/desk. It’s like something out of experimental theater, yet wholly credible given the milieu. And of course the cast puts things across in an almost mortifying way. As Adela and Dora, respectively, Spindola and Velázquez dispense with all vanity, flaunting their aging flesh with a “screw the world” attitude even as their characters are subjected to humiliations both malicious and random. The two wind up becoming their own dupes in a horrifically predatory world, a world that, judging from Ripstein’s choice of closing song, has subsumed his whole country.