“You’re really pretty.”

“I like your overalls.”

“I like your bag.”

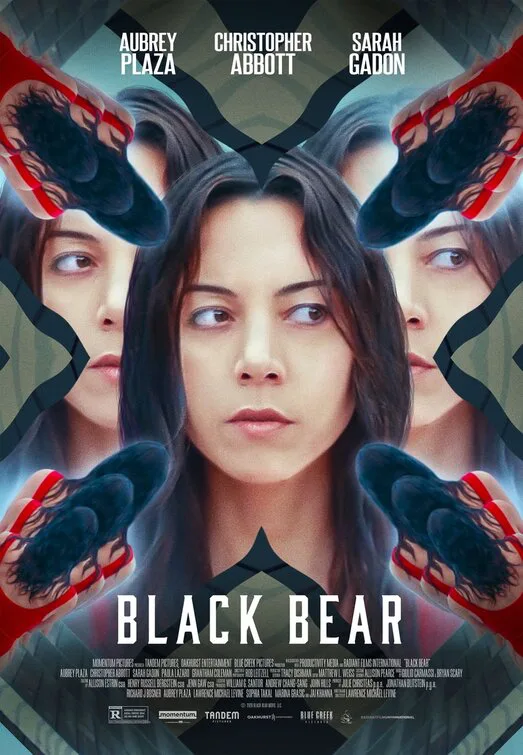

Immediately upon meeting each other, the two women in “Black Bear”—played by Aubrey Plaza and Sarah Gadon—blurt out compliments. But they don’t feel genuine. Are the compliments a disarming tactic? Is it a way to break the ice? All I know is that these moments felt extremely familiar: those compliments coming from two women who were clearly not thrilled to be meeting one another and probably didn’t think the bag/overalls were particularly cute created a very uneasy sense of deja vu. “Black Bear” is ambitious for itself in its many layers of meta, but the observational moments of behavior is where the film soars. Writer/director Lawrence Michael Levine has created a highly self-conscious work that comments on itself and then comments again. Levine’s sense of humor is one of his saving graces, and that’s particularly true here. This is a disturbing film, and much of it is unpleasant, but it’s also very, very funny.

Allison (Aubrey Plaza), in a red one-piece bathing suit, sits on a dock staring out at a lake as unruffled as a mirror. She’s a writer/director and has come to a house in the woods to work on her next script. The house is owned by a couple, Gabe (Christopher Abbott) and Blair (Sarah Gadon), transplants from the city, who have a vision of their home as a haven for artists. Things don’t quite work out that way. On Allison’s first night, they all get drunk, even though Blair is pregnant, and Gabe and Blair fight in front of Allison, and eventually fight about Allison. Three is most definitely a crowd, and Allison’s strange behavior doesn’t help matters. Blair says to Allison, and it’s an accusation: “You’re really hard to read.” Allison deadpans, “I get that all the time.”

What’s this all about? Whatever you might guess is up-ended when the scenario rewinds, starts again, with the same actors, in the same location, only the circumstances are different, and the characters have been rebooted into another scenario. Maybe the rewind is Allison’s discarded script draft, her attempt to break through writer’s block, her experimentations with genre and story. Maybe none of it is real. “Black Bear” often “reads” like a horror film, but the second half goes full-blown hand-held Cassavetes, with nods to “A Woman Under the Influence” and “Opening Night,” where Allison, so drunk she can hardly stand, is required to “play” a scene in the fictional film she’s acting in, directed by her manipulative self-styled “auteur” husband (Abbott). The music—composed by Giulio Carmassi and Bryon Scary—is appropriate for a horror or a slow-burn thriller, highlighting the subterranean upheaval in all of this. It is not the end of the world when a couple bickers over nothing. It is not world-shattering to have a difficult time playing a scene when you’re an actress. But to the people involved, it can feel like the end of the world. This is what Levine captures.

Levine has explored destabilizing relationships before in the films he’s written, acted in and/or directed, in partnership with his wife Sophia Takal (“Black Bear” is dedicated to Takal). Takal’s first full-length film, “Green,” featured Levine and Kate Lyn Sheil as a married couple whose relationship is shaken up by the entrance of a third, played by Takal. In “Gabi on the Roof in July,” directed by Levine, Takal again plays a destabilizing force, this time for her painter brother, played by Levine. “Wild Canaries,” written and directed by Levine, is a murder-mystery featuring Levine and Takal playing a curious hipster Brooklyn couple investigating a murder (shades of Woody Allen’s “Manhattan Murder Mystery“). Takal’s wonderful film “Always Shine” (which I reviewed for this site), was written by Levine, who also played a small role. “Always Shine” starred Mackenzie Davis and Caitlin FitzGerald as actresses whose friendship—and selves—fracture during a weekend away. (For my column at Film Comment, I wrote about Sophia Takal’s work.) Takal recently directed “Black Christmas,” a remake of the 1974 cult classic, while Levine was working on “Black Bear.” This is a very interesting artistic partnership. The surface of life in these films, and in “Black Bear,” is often banal, polite, obnoxiously liberal and literate, while underneath roars a river of unmanageable “unacceptable” feelings like rage and envy. Social niceties conceal chaos. The films these two have made together often feature artistic “types”—writers or actresses or painters—or a director like Allison—entering an environment where they are out of their element. The unfamiliarity of the surroundings reveal cracks in everything they have established for themselves.

Aubrey Plaza has been doing excellent work for years. In “Ingrid Goes West,” she played a Rupert-Pupkin-type for the social-media-“influencer” era, and it was one of my favorite performances that year. Here, as Allison, you don’t know whether or not to believe one word the woman says, and Plaza revels in keeping people guessing. She is, by turns, snarky, wrecked, terrified, desperate, undone. Nothing is stable, but her deadpan face tells no tales. This is Plaza’s very specific wheelhouse. She never makes a wrong move, and yet you never know what she will do next. Blair and Gabe are easy targets to someone like Allison. She barely has to do anything and their relationship starts to shatter. Both Abbott and Gadon are excellent, at first playing characters who are so annoyingly passive-aggressive they can barely have a conversation. Together, they nail the toxic quality of such a relationship. We all know couples like this. We all know how much we hate to hang out with couples like this. Then, with the film-rewind, they are transformed into “artists” giggling at their own cleverness, high on their own fumes of “creativity,” giggling as Allison falls apart.

There are elements here reminiscent of “Persona” and “Mulholland Drive” (also present in “Green” and “Always Shine”), where the two women’s personalities are in a state of flux, their identities at times interchangeable. Nobody can keep their form intact. Selves bleed into each other, a dangerous merging takes place. This seems to reflect an anxiety at the heart of the film: Does anything make us unique?

Levine’s story structure doesn’t quite hold together. It’s a little top-heavy. But the undercurrents he revels in as a storyteller, the dark underbelly of our social interactions, this is the engine of “Black Bear,” and it’s a powerful engine. All of those things we’re trying to suppress with small talk, jokes, ideological debates, even our compliments about bags and overalls … what’s underneath all of it? What on earth are we all so afraid of? What are we trying to hide?

Now playing in select theaters and available on demand.