Director Sophia Takal is interested in the murky powerful undertows beneath female friendship, the dark sides of supposed “safe spaces” and just how threatening close female friendship is to whatever status quo that might exist. The two films (so far) from this confident young filmmaker, “Green” (2011) and her latest, “Always Shine” (which, in many ways, is an unofficial sequel of “Green,” in terms of Takal’s exploration of these loaded topics), are deeply unnerving. The atmosphere of menace seems to emerge from the landscape itself or directly from the characters’ psyches. The “pathetic fallacy” is omnipresent and stifling. “Always Shine,” written by Lawrence Michael Levine (who appears in both “Green” and “Always Shine”) moves explicitly into a horror film realm, but the real engine of the film—as it was in “Green”—is the relationship between the two women at its center.

Two 20-something actresses, Beth (Caitlin FitzGerald) and Anna (Mackenzie Davis), take a weekend road trip to the isolated Big Sur home of Anna’s aunt. Beth’s career has started to gain a kind of momentum. Yes, she is always cast as the obligatory naked blonde in horror movies, but still, she’s getting paid to do what she loves. Anna, on the other hand, seethes with jealousy. Anna has more ambition than Beth. Anna is a better actress than Beth (they both acknowledge that). But Beth is softly agreeable and girlishly pretty with a submissive voice and manner. Anna is off-puttingly emotional, easily hurt and smears on bright red lipstick like a warning flag, rather than a seduction. They are both blonde and slim, and there are multiple shots of each, seen from behind, and you can’t tell them apart. This intensifies Anna’s hurt: They’re similar “types.” Why Beth and not her? Especially when she wants it more?

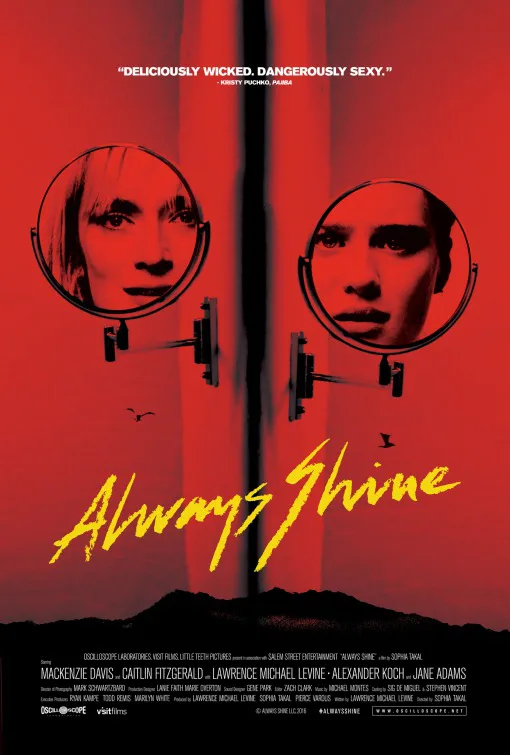

This is a film about acting, as the trompe l’oeil opening sequence makes clear. The sequence shows what appears to be two auditions, with the actresses reciting lines staring into the camera, as off-camera male voices speak to them. But these scenes lead the audience astray before doubling back to provide delayed clarity—all the more satisfying because of the delay. Nothing is what it seems. That’s show biz, first of all, and these girls have devoted their lives to illusion and performance. On the other hand, things are exactly what they appear to be, and the brain resists what is plain as day, perceiving illusion where there is none. “Always Shine” is a persona-swap movie, clearly influenced by “Persona” and “Mulholland Drive,” two other films featuring actresses who experience a dangerous and disorienting merging, boundaries obliterated, the quest for identity totally irrelevant in the world of theatre, where you—the person—are supposed to disappear anyway.

Despite the tension that is there from the get-go, Beth and Anna take hikes, go out for a drink at a nearby bar, hang out on the deck. The dynamic is jagged and unpredictable. Anna seems downright unstable. Beth is intimidated by Anna and it’s not hard to understand why. Anna takes Beth’s success as a personal affront. Not only that, but the fact that Beth doesn’t share good news (she’s included in the “Young Hollywood” issue of a magazine, she’s been offered the lead in a new movie, a step up) is seen as treachery by Anna. Anna’s outrage that Beth would ever dare complain about anything completely silences Beth.

To complicate matters, Beth is not blameless, although she operates in a miasma of plausible deniability. Beth engages in subtle moments of sabotage throughout. In one painful scene, Beth co-opts the attention of a guy Anna seems interested in and does so in a way that is impossible to clock. Anna is not wrong about Beth.

This is such an accurate observation about what can happen between actresses when one of them starts to pull ahead. Oscar Wilde, in his essay The Soul of Man Under Socialism, expressed it perfectly: “Anyone can sympathise with the sufferings of a friend, but it requires a very fine nature—it requires, in fact, the nature of a true Individualist to sympathise with a friend’s success.”

Cinematographer Mark Schwartzbard makes the majestic Big Sur landscape seem like an emanation from the emotions of the women: Waves crash against the rocks, thick fog rolls in, trees stand like sentinels. There are specific choices that work beautifully, like the camera following Beth as she paces on the deck in an increasingly frenzied manner. There’s one great shot where the two women turn into three: Anna, alone onscreen, back to the camera, stares into a mirror. In the mirror is a reflection of her face, as well as a reflection of Beth’s face, off-camera, but still present in the background. Editor Zach Clark (whose directorial effort “Little Sister” was one of the pleasures of this fall) intercuts the action with brief glimpses of violence, so brief you can’t tell what’s happening, figures, darkness, movement, accompanied by screams, cut short. “Always Shine” is not a mumblecore kitchen-sink-reality film. It’s highly stylized. Some of the stylistic choices work better than others. The horror tropes are familiar, bordering on cliche. What is truly terrifying is the cataclysm opening up between the women, the volatility of their dynamic.

None of this would be possible without the extraordinary performances of these two actresses. Mackenzie Davis gives a star-making performance. A maelstrom of emotions churn all over her expressive face: sharp anger, wounded hurt and baffled confusion. This is a woman who needs more space to maneuver, who needs to live in a world that lets her be, lets her be as loud, as passionate, as emotional as she is. It’s how she’s wired, and it’s devastating that nobody wants it—not men, not casting directors, not Beth, not anyone. Caitlin FitzGerald portrays a woman whose submissiveness is habitual and learned. But when her anger starts to bubble up, when she finally has had enough of being Anna’s punching bag, you see that Anna has perhaps underestimated her friend all along.

In this universe, looking at your best friend is like looking into a mirror that distorts, turning you back on yourself. This distortion doesn’t have to do with competition for male attention or acting jobs. What it has to do with is power. Even mentioning female power on Twitter is enough to get you death threats these days, which shows the resistance to the idea in general. Takal has supersonic hearing when it comes to this whirlpool of emotions and resistance. Why can’t both women be powerful? Or is only one allowed to rise because God forbid there are two powerful women running amok like a Robert Crumb comic on steroids? What would happen if both women lived in a world where female power was a given? What would that even look like? And—most importantly—why, why is that so scary?

“Always Shine” is an immersive nightmare of merging, over-identification, and projection. Its strangeness (and I yearned for more strangeness) is part of the fascination. The true horror here is emotional. These women feel pressure to be one and have an equal desire to shatter the illusion of one-ness forever.