This review was originally published on December 4, 2020 and is being republished for Black Writers Week.

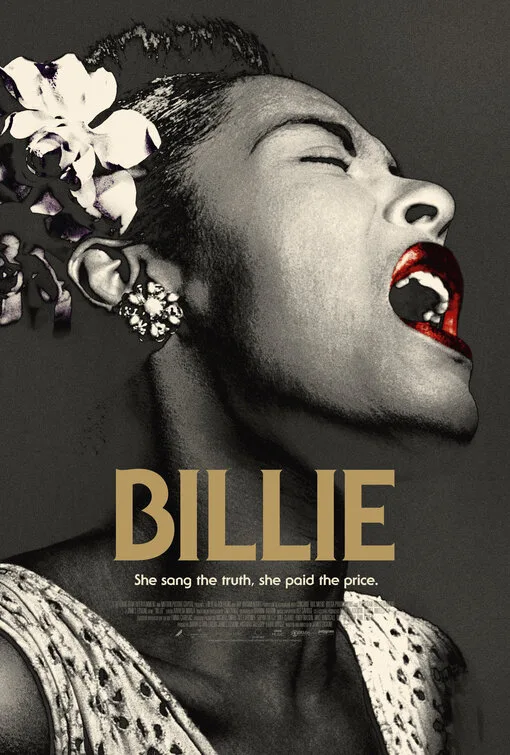

For nearly a century, Billie Holiday’s sultry voice has been the soundtrack to both lonely nights and mournful mornings. Her visage, an aperture into her troubled soul. Singer and friend Sylvia Sims observed, “I saw the whole world in that face. All of the beauty and all of the misery.”

Holiday’s beauty and misery made her into a tragic figure to everyone except Linda Lipnack Kuehl. A talented journalist who wrote a biography about the songstress 20 years after her gradual death, Kuehl dedicated a decade to interviewing the friends and artists who knew Holiday best. Before completing her work, Kuehl died suddenly in February 1978. Her book was never finished. Her tapes were never heard.

Director James Erskine’s fascinating documentary “Billie” follows in Kuehl’s footsteps by unearthing her manuscript and recordings to re-contextualize the life of the critically-acclaimed Holiday, who died at the age of 44. Just as intriguing as Erskine’s subject is the time capsule aspect of the clips he selects. For instance, Tony Bennett wonders aloud why girl singers all “crack up.” Others intimate that Holiday sought out men prone to violence because of her masochist personality. These were the prevalent views from the 1970s. In “Billie,” Erskine adroitly paints an unvarnished portrait of a generational talent, the ethics and politics of the generation she entertained, and the journalist transfixed by the singer’s crooning spell.

Erskine lends new potency to the woman known as Lady Day by virtue of her performances. For instance, “Billie” opens with colorized footage of the songstress, in a shoulder-less dark satin dress, singing “Now or Never.” While her vocal is coated by her warm sensual appeal, seeing her beautifully colorized with her coy smile and tempting eyes imbues the clip with the same vibrancy she must have shown in life.

Holiday, in her words, lived a hundred days in any single day. Her friends describe her in interviews as a sex machine who took part in relationships with women, men, and prostitutes. One person defends her by saying, “She wasn’t a slut. She just lived fast.” A lover recalls that in her furs and diamonds she looked like a panther stalking her prey. Holiday possessed a sexual freedom that still feels revolutionary for women today. Her dalliances with women were so well-known, onlookers referred to her as Mr. Billie Holiday. The total salacious portrait is enthralling at every turn.

By the age of 13, Holiday earned money as a sex worker, too. Her former pimp, Skinny Davenport, a name that sounds too on-the-nose for even Hollywood, casually recounts abusing Holiday. His blasé laugh and insistence that Holiday loved being hit makes for a frightening listen. Even more vexing is the consensus of his opinion. A psychologist describes her as an impulse-driven psychopath. Memry Midgett, a black woman pianist, agreed that the singer wanted the punishment. Their viewpoints are a complete misunderstanding of the extreme emotional trauma suffered by battered women that sometimes leads to a cycle of violence. In the case of Lady Day, it was her husbands Jimmy Monroe and Johnny McKay.

Other figures such as Pigmeat Markham and dancer Detroit Red recount the open drug-taking of the era. Markham explains how smoking reefer was so commonplace when Holiday performed at the Apollo that she came out to a cloud of smoke thick enough for a contact high. The risqué atmosphere, with its coterie of pimps, built an environment where her drug habit and supply of brutal men was inexhaustible. In a different era, with greater understanding, she might have found help. Then again, one can’t forget the recency of Amy Whinehouse either. And as with the documentary “Amy,” we feel helpless during “Billie” as her immense talent withers away. Erskine subtly juxtaposes the clarity in Holiday’s swooning vocals, heard in the colorized performances, against the sound of her later throaty slurring interviews. The audio foreshadows Holiday’s later visual decline caused by the ravages of booze, weed, opium, cocaine, and heroin.

Much of “Billie” is composed as one long performance by Lady Day. Her songs not only comprise the documentary’s formidable soundtrack, their autobiographical qualities are like lines of monologue from the singer herself. Lady Day’s performance of “Don’t Explain,” for example, sees her bone-thin, barely recognizable, and intimates the immense desolation in her personal life. “Fine and Mellow,” where she seductively interplays with her close friend, saxophonist Lester Young, relates her sibling-like affection for Young as opposed to her attraction toward terrible men.

“Billie” is steeped in that kind of melancholy. Not just in matters of the heart, but political and racial, too. The Federal Government’s narcotics bureau stalked the singer for over a decade and employed people in her inner-circle as informants. Kuehl’s guiding questions, heard in her recorded interviews, ask whether the government’s targeting of Holiday sprung from her celebrity: She would make a name-making trophy for any agent who captured her. Kuehl also wonders how much Holiday’s political stances, heard in songs like “Strange Fruit,” which unflinchingly compares horrific lynchings to dead delectables, informed the government’s dogged pursuit. Showing tremendous foresight, Kuehl explores how white men like Holiday’s producer John Hammond, her agent Joe Glaser, and bandleader Artie Shaw posed as allies only to betray her. These hurdles, which Erskine smartly connects, are emblematic of the traps other black entertainers faced (see Joe Louis and Ray Charles) and to a point, with regards to fake allyship, they still face.

Kuehl was also drawn to the subject of appropriation. Billy Eckstine, one of Holiday’s favorite singers, criticized white critics who bestowed the white Paul Whiteman with the title of “King of Jazz” or Benny Goodman as the “King of Swing.” Herself a white woman from a middle-class Jewish family from the Bronx, Kuehl knew the implications of her telling a black woman’s story. In some ways, Erskine, a white director, must also be aware of the connotations of him making a Holiday documentary. Both Kuehl and Erskine have the wherewithal to provide themselves cover by letting the voices of the black interviewees take center stage. Even so, Erskine includes a few too many splashes of Kuehl: From intimating a relationship between her and Count Basie, to a conspiracy theory surrounding her death.

But these slight digressions aren’t enough to unravel “Billie,” because the Lady in Satin’s music binds all of the tangents together. As Sims observed, there’s a truth in every note Holiday sings. A truth that’s not only undeniable, it’s unshakable too. And the interviews, with many figures like Charles Mingus and Count Bassie, who have long-since departed, retell the era in exciting detail. Erskine’s “Billie” is an honest memorial to the rich talent, and the arresting traumas that made the voice of a generation.

Now playing in select theaters and available on demand.