As relatively handsomely mounted as this movie is, it’s also kind of a shambles. Had I not read a press release about it prior to attending its New York screening, I would not know who the damn thing was even about until a whole half-hour in.

Advertising itself in an opening credits text, as being “Based On An Extraordinary Life,” the movie opens in a funeral home. Robert Forster, sporting a gray mustache, upbraids D.J. Qualls for coming to the place wearing sneakers. The person in the coffin—this is perhaps a very poorly attended funeral, or maybe this meeting is before the actual service, nobody tells me anything in this movie—is Benny, the brother of Forster’s character, whom Qualls calls Joe. Benny, Joe tells the Qualls character, who’s a writer doing something about Joe, was a person of substantial achievement, a nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize, and stuff like that. Ok, so is this movie about Ben?

Not really—it flashes back to the 1919 birth of Joe in Montreal, and his mother’s irritation that he’s not a girl. Ben is his younger brother, and as kids the two are fascinated by circus strongmen. Just as we’re getting settled in for a nice long flashback, and some illumination as to who the movie is going to pick as its central character, we’re back at the funeral home.

Eventually the brothers haul a sign in front of a storefront with the name “Weider” on it, and I’m like, “oh, of course, this is about Joe Weider, the bodybuilding guru I know almost nothing about except that he was a bodybuilding guru.”

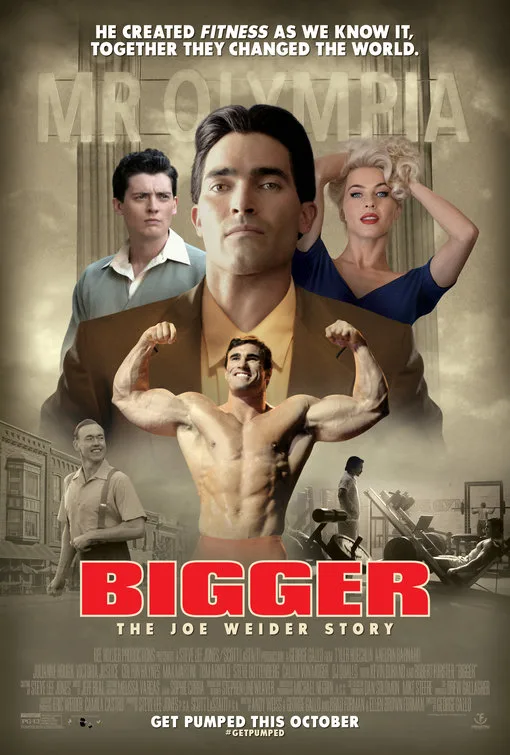

At this point the movie (directed by George Gallo from a script Gallo co-wrote with Andy Weiss, and, to judge by the spacing out of the credits, another script that was written by Brad Furman and Ellen Furman) settles in to a pretty conventional and linear and coherent biopic mode. Joe Weider, played with square-jawed stolidity by Tyler Hoechlin, is a person of very narrow focus. Obsessed with the cultivation of physical perfection, he spends hours drawing an ideal Adonis. He concocts exercise routines and studies diet, and puts his findings in a fanzine that expands into a genuine mainstream magazine. He is met frequently with anti-Semitism both casual and pressing, and when he and Ben get into the mainstream of what in the ’30s and ’40s was still a very small culture, they make a lifelong enemy of …well, in this movie it’s an entirely fictional character named Bill Hauk. Hauk is represented as a bodybuilding contest promoter and publisher who’s a loudmouth bigot with thin skin and violent tendencies.

“Bigger” portrays the bodybuilding field as pretty steadfast, if not wholly thrifty, brave, clean and reverent. Some characters are repelled by Weider’s fascination with male physique, thinking him gay. He is not, not that there would have been anything wrong with that, and the movie skates over the homoerotic side of the culture entirely. Steroids and prior performance-boosters don’t get any mention either. Weider has a resolve that’s kind of Randian—Harold Roark with a barbell. A guy like him can make an interesting movie, but “Bigger,” executive produced by Ben Weider’s son Eric, is a bit of a secular hagiography. Joe is portrayed as a prophet, envisioning planet fitness, so to speak, before anyone else.

His dreams culminate when he discovers an Austrian bodybuilder named … wait for it … Arnold Schwarzenegger. Uncannily, young Arnold’s physique was prophesied by Joe in his own drawings from back in the ‘30s. The movie picks up a little steam at this point, not least because of Calum Von Moger’s really uncanny resemblance to the young Schwarzenegger (not to mention his spectacular approximation of the icon’s accent). There are some comic grace notes added by his presence as a character too. Robert Forster’s old Joe, in voice-over, reflects that his ambitions had been driven by the love he never got from his mother; as the movie shows younger Weider training young Arnold, Joe continues, “As it turns out, Arnold had need too.” At which point I could barely repress a snort of laughter and saying back to the screen, “Tell us about it.”