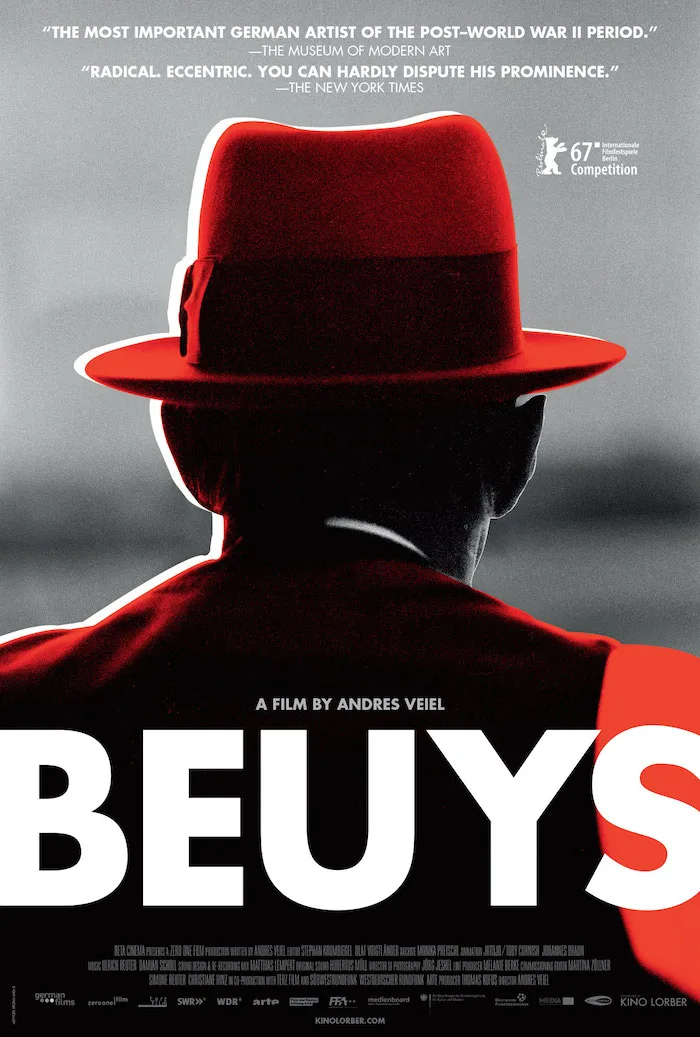

For devoted admirers of Joseph Beuys, the celebrated German artist and activist, Andres Veiel’s new documentary will likely be a treat, with its extensive footage of the man in his element. Yet for those viewers, such as myself, who wouldn’t know Beuys from Adam, Veiel’s picture is frustratingly opaque to the point where it requires additional homework in order to be understood. So vague is the picture about the meaning of the artworks it presents that they proved to be of little interest to me, until I researched them afterward. Far more compelling is Beuys himself, with his signature hat, haunted gaze and outspoken belief that art can be a vehicle for communication.

Bookending the film are arresting shots of Beuys locking eyes with the screen, peering out at the “anonymous viewer” that he desires to reach with his artistry. Like David Lynch or Andy Warhol, Beuys crafted a persona for himself that served as somewhat of a protective cocoon. Rather than explain his technique or intentions, he articulated his philosophy at length, delivering such memorable soundbites as “Every normal situation is art.” His goal, above all, was to provoke people into engaging with the issues embedded in his work, and that is where Veiel’s “Beuys” comes up short by repeatedly failing to illuminate the substance beneath the spectacle. What we have here, sadly, is a failure to communicate.

Whereas Brett Morgen’s often riveting yet overrated “Jane” sprinted at too tight a clip through the breakthroughs made by its titular subject, while leaning too heavily on an obtrusive Philip Glass score, “Beuys” has the opposite problem. The editing is positively sluggish at times, holding for a prolonged period on still images without bothering to provide context for them. Five talking heads are identified by name but their specific relation to the artist is rarely addressed. Only the inventive atonal score by Ulrich Reuter and Damian Scholl kept my attention transfixed for long stretches of the picture. The music conveys a sense of urgency and magnitude that the rest of the film lacks, even as it hails Beuys for his global influence.

Take for example, the brief sequence regarding the 7,000 oak trees that the artist began planting in 1982, a controversial act that dramatically altered the cityscape of Kassel, Germany. Juxtaposed alongside each seedling was a basalt stone that eventually became dwarfed in stature as the tree grew. We later see various citizens pitching in to help plant the trees—but to what end? I was reminded of Ai Weiwei’s recent public art exhibition in New York City entitled, “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors,” that consisted of various structures designed to disrupt the flow of pedestrians not unlike the barriers erected to block refugees from immigrating to safety. What made Ai Weiwei’s work so powerful was its clarity of purpose. Though art critic Caroline Tisdall insists that Beuys’ “7000 Oaks” is one of the “most incredible works of the 20th century,” neither she nor Veiel make an effort to explain why, apart from its vast scope.

What sort of tangible change did Beuys’ artistic career have on society in terms of raising awareness as opposed to growing trees? Does his conviction that art could ultimately make democracy “a reality” amount to, as one critic argued, “hollow rhetoric”? There’s no question that Beuys is a captivating speaker, and the most entertaining sections of the film consist solely of archival footage in which the artist locks horns with stuffy skeptics at debates as his young fans cheer. His anarchic tendencies caused him to get booted from his teaching position after drawing the ire of colleagues with his puzzling stunts, such as when he grunted with animalistic fervor into a microphone while standing before a roomful of bewildered governmental bigwigs. To him, art had expanded far beyond its traditional form, which he felt could exist solely within the hermetically sealed environment of a museum, not unlike the one satirized in Ruben Östlund’s “The Square.”

Just as Terry Notary’s uncompromising performance artist in Östlund’s film galvanized a crowd of wealthy sophisticates, forcing them to cast off their own civilized façades in order to fight back, Beuys favored art that leapt out at viewers in three dimensions. He believed in a politicized art that could be utilized as a weapon against “the enemy,” that artists must look to the future beyond capitalistic and communist systems of government, and that freedom could not be achieved when beholden to the power of money. These statements make it sound as if Beuys were running for office, and indeed he helped co-found the German Green Party, which he hoped would serve as a subversive force in his country’s political climate. Yet according to Veiel’s film, the Green Party eventually turned its collective back on the artist, who was, in the words of his pupil, Johannes Stüttgen, “dropped by his own people.”

While the film hints at how Beuys may have worked himself to death, it neglects to tell us that he died at age 64 of heart failure, just four years after starting the “7000 Oakes” project. In fact, the vast majority of Beuys’ personal life is left unacknowledged here, particularly his past as a Hitler Youth. Aside from a fleeting shot of young Beuys wearing a swastika patch while flying a model plane, we get no sense of his evolving views regarding Nazism and how they may have fueled his compulsion to create, perhaps as a method of healing. When it is revealed that Nazis were among the early participants in Beuys’ Green Party, Stüttgen mentions that they were welcome because of their “holistic philosophy,” a causal aside that only raises more questions.

We never hear of Beuys’ proposal for an Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial, which would’ve been most enlightening considering the work he produced, with its emphasis on empathy. Instead, we hear Beuys recount his famous story of being shot down while serving in WWII, after which he was rescued by nomadic tribesman who wrapped his body in felt and animal fat, two elements that went on to have crucial roles in his subsequent artworks. This story would seem to be revelatory, if it weren’t fictionalized, as historical records have allegedly proven. What a fascinating film this could’ve been had it explored the reasons behind Beuys’ attempts to mythologize his own past. Instead, Veiel simply leaves us with audio of the interviewer questioning her subject’s interpretation of the events.

In terms of provocation, “Beuys” could certainly provoke me into reading a book on its subject, a fine alternative to sitting through this evasive misfire again. I’m convinced that Beuys’ voice is a valuable one to have revived in the modern sociopolitical discourse, but this film is not a sufficient vehicle for it. Only his 1974 performance art piece, “I Like America and America Likes Me,” is given a frank analysis courtesy of Tisdall. Beuys flew to America and locked himself in a room with a coyote for three days, never once stepping foot on U.S. soil, before flying home, transported to the airport by ambulance while covered in felt. Tisdall says that the coyote is meant to embody the sort of mischief that “white settlers attributed to Native Americans,” and I’ll take her word for it. As for myself, I couldn’t help sympathizing with the coyote as it tore mouthfuls of felt from Beuys’ costume, striving to reveal the human being shrouded within the artifice.