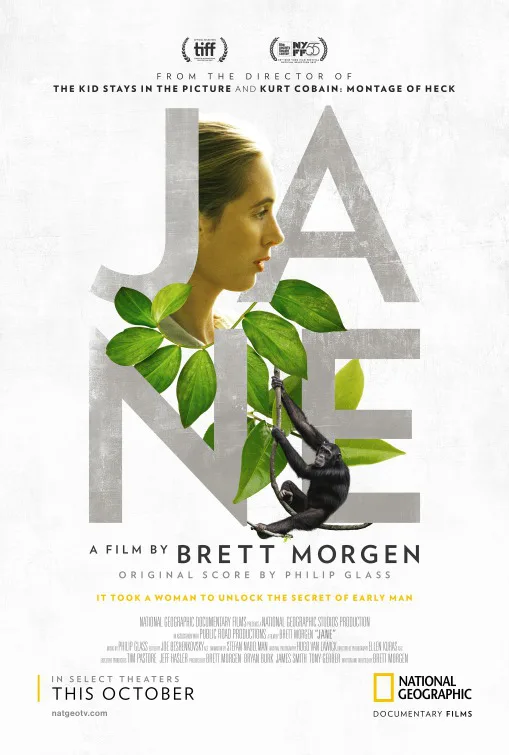

Biographical documentaries of famous people are typically dull affairs, the kind of thing that falls into hagiography or the kind of talking-head, then-this-happened adoration more at home in the 60-minute television format on PBS than in a feature film. There are very few filmmakers who have defied this trend as completely as Brett Morgen, the director of “Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck” and “The Kid Stays in the Picture” (about Robert Evans). He makes films that feel like extensions of his subject matters, channeling their creative spirit in the form of his filmmaking more than just detailing what happened in their lives. So it’s cinematic justice that over a hundred hours of footage of Jane Goodall crossed paths with Brett Morgen, as both are pioneers in their field, and only Morgen seems capable of shaping that footage in such a unique, captivating, inspiring way as in “Jane,” one of the best documentaries of the year so far.

“Jane” is that rare documentary that works in equal measure for those who know a great deal about Jane Goodall and those people who don’t know a thing. Most people probably think they know all they need to know about Jane Goodall. She watched chimps, right? Her research was essential to understanding not only the way we interact with the natural world but our place in it, but hers is not a name like Kurt Cobain that gets thrown around in conversations much in 2017. “Jane” fully elevates the scientific pedestal on which Jane Goodall should be placed but it does so in part by humanizing her, revealing the challenges she faced and discoveries she made as more than mere National Geographic footage you might see in a Science class.

Morgen structures his film relatively chronologically, allowing Goodall to tell her own story as we see footage of her in the wild. There’s a fascinating structural element of “Jane” in that the footage doesn’t contain interviews or dialogue, and so we’re watching Jane, the chimps, and the other humans who would come to Gambe, in a way that’s not dissimilar from the way Goodall observed her subjects. And there’s the added sense of disconnected observation that comes with time, and in the manner that Goodall herself is analyzing her own story in the way that someone might analyze the actions of a family of chimps. The parallel is clearly intentional, especially as “Jane” becomes more and more about how the lessons that Goodall learned in the wild informed her entire life, including even teaching her lessons about motherhood.

That’s a theme of “Jane” as we’re introduced to Goodall’s supportive mother in the opening scenes, see how Jane observes the motherhood of the chimps she’s studying, and then see her maternal instincts on display with her own child. Morgen very subtly does this in his films—drawing thematic undercurrents that move through the work without overriding the informative chronology of it all. There’s a fluidity that can be breathtaking to watch, especially as that motion is accompanied by Philip Glass’ best film score in years. You should be warned that it’s “very Glass,” and I found it somewhat overwhelming at first, but I quickly couldn’t imagine the film working without it. It becomes an essential part of the film because of the aforementioned lack of an abundance of archival interviews, meaning that Goodall’s modern voice and Glass’ compositions become our primary sources for information and inspiration.

“Jane” is filled with fascinating anecdotes and insights, such as the fact that Goodall was never nervous about going to the wild to observe chimps because we didn’t really know about the aggression of the species when she chose to do so. She didn’t know to be scared (but would learn about the violence inherent in the chimp population). Goodall made headlines around the world when she filmed a chimp using a branch to obtain termites from a hole for nourishment. It may not seem like a big deal now, but it was once thought that humans were the only species to use tools, and the fact that a chimp used a branch as a tool shook the world, especially in the offices of religious leaders. The footage around the first time that Goodall really made contact with the chimps—when they trusted her enough to get close—is still breathtaking. It’s incredible to consider that footage this old of a chimp taking a banana from a woman for the first time ever would make for one of the most unforgettable scenes of 2017. A baby chimp learning how to walk is on that list of 2017 images I won’t forget as well.

Goodall herself is a forthcoming and fascinating interview subject—another testament to Morgen’s work as a narrator. “Jane” feels like a film that couldn’t have been made without the valuable insight gained through time. We see so many documentaries that want to be current and timely that they don’t realize the value of chronological distance from a subject. In a sense, we’re watching the impact of Goodall’s evolution from a young adventurer to a groundbreaking scientist to a wife and mother. And it’s through her self-analysis of that evolution that Morgen draws a line through fifty years of research and an entirely different species. As he has in his other films, he’s saying to us that it is through these pioneers that we can see the best in ourselves and the potential of the human intellect and desire to learn. But he never loses his filmmaker’s desire to entertain at the same time. It’s that balance of both—the genius of both the subject and the filmmaker—that make “Jane” such a rewarding experience.