Aman boards a London bus, locks eyes with another man and immediately starts to fight with him. Thrown off the bus, they chase each other through the streets and eventually end up in adjacent hospital beds, still ready to fight. One is a Croat, one is a Serb, and so they hate each other.

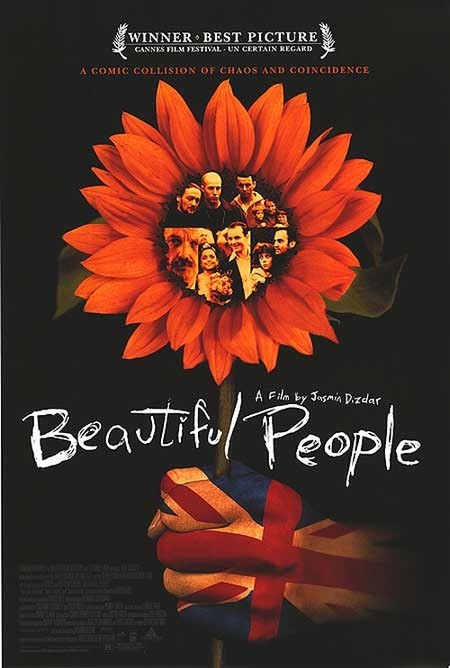

Ah, but hate is not limited to Croats or Serbs from Bosnia. In the next bed is the Welsh Firebomber, a man who torched the holiday cottages of 20 English weekenders before burning himself on the face. Elsewhere in “Beautiful People,” we see three skinheads attacking a black kid, a foreigner who is mistaken for a thief while trying to return a wallet, and the beat goes on even at the breakfast tables of the ruling class: “God,” says the wife of a government official, “Antonia Fraser is so bloody Catholic.” “Beautiful People,” written and directed in London by the Bosnian filmmaker Jasmin Dizdar, is about people who hate because of tribal affiliation, which is a different thing from hating somebody you know personally and have good reasons to despise. One of its interlocking stories involves a pregnant Bosnian woman who wants an abortion because her baby, the product of a rape, “is my enemy.” The movie loops and doubles back among several stories and characters, like Robert Altman’s “Short Cuts” and Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Magnolia.” The insights in one story cast light on the problems of another, and sometimes the characters meet–as when a young woman doctor falls in love with a patient and brings him home to meet her stuffy family. Nor are the moral judgments uncomplicated. Although she explodes when her family condescends to the man, the fact remains that he speaks only about six words of English, and so her own affection for him is condescending, too.

The most complex story involves a young heroin addict named Griffin (Danny Nussbaum), who has always been a trial for his parents (“Remember sixth form,” his father asks, “when all of the teachers went on strike because no one wanted to teach him?”). As part of an involved attempt to attend a football match, Griffin stumbles onto an airfield, falls asleep on an air freight pallet and is dropped by parachute into Bosnia as part of an airlift of United Nations aid supplies.

This has the aroma of an urban legend to it, like the scuba diver who was scooped up by a firefighting airplane and dumped onto a forest fire. In “Beautiful People,” it works like one of those fairy tales where a naughty child gets his comeuppance by trading places with one less fortunate. What happens here is that Griffin, dazed and withdrawing, stumbles around the war zone and ends up behaving rather well.

There is another character stumbling there, too: a BBC war correspondent who loses his mind in the chaos of blood and suffering. Shipped home, he tries to check himself into a hospital to have his leg amputated; he has “Bosnian syndrome,” a doctor whispers, and perhaps he feels guilty to have two legs when so many do not.

I have made the film sound grim. Actually it is fairly lighthearted, under the circumstances; like “Catch-22,” it enjoys the paradoxes that occur when you try to apply logic to war. Consider the sequence where the foreigner walks into a cafe, annoys a British woman with his friendliness and then, after she stomps out, he sees she has forgotten her billfold. He runs after her, is mistaken for a madman and is injured in traffic. Another urban legend? Not if you saw the story only last week about an African-American taxi passenger in Chicago whose innocent presence so terrified his immigrant driver that the cabbie careened at top speed down one-way streets looking for a cop.

Why are we so suspicious of one another? It may be a trait hard-wired by evolution: If you’re not in my tribe, you may want to eat my dinner or steal my mate. The irony about those two Bosnian patients, fighting each other in the London hospital, is that they’re the only two people in the building who speak the same language. So to speak.