“Barney’s Version” tells the story of a man distinguished largely by his flaws and the beautiful woman who loves him in spite of them. What she sees in him I am not quite sure. He is a precariously functioning alcoholic and chain smoker of cigars, balding and with a paunch, a producer of spectacularly bad television shows, and a fanatic hockey fan. Since he lives in Montreal, many good women might forgive the hockey, but he is also hostile toward her friends, rude at dinner parties, and has bad taste in ties.

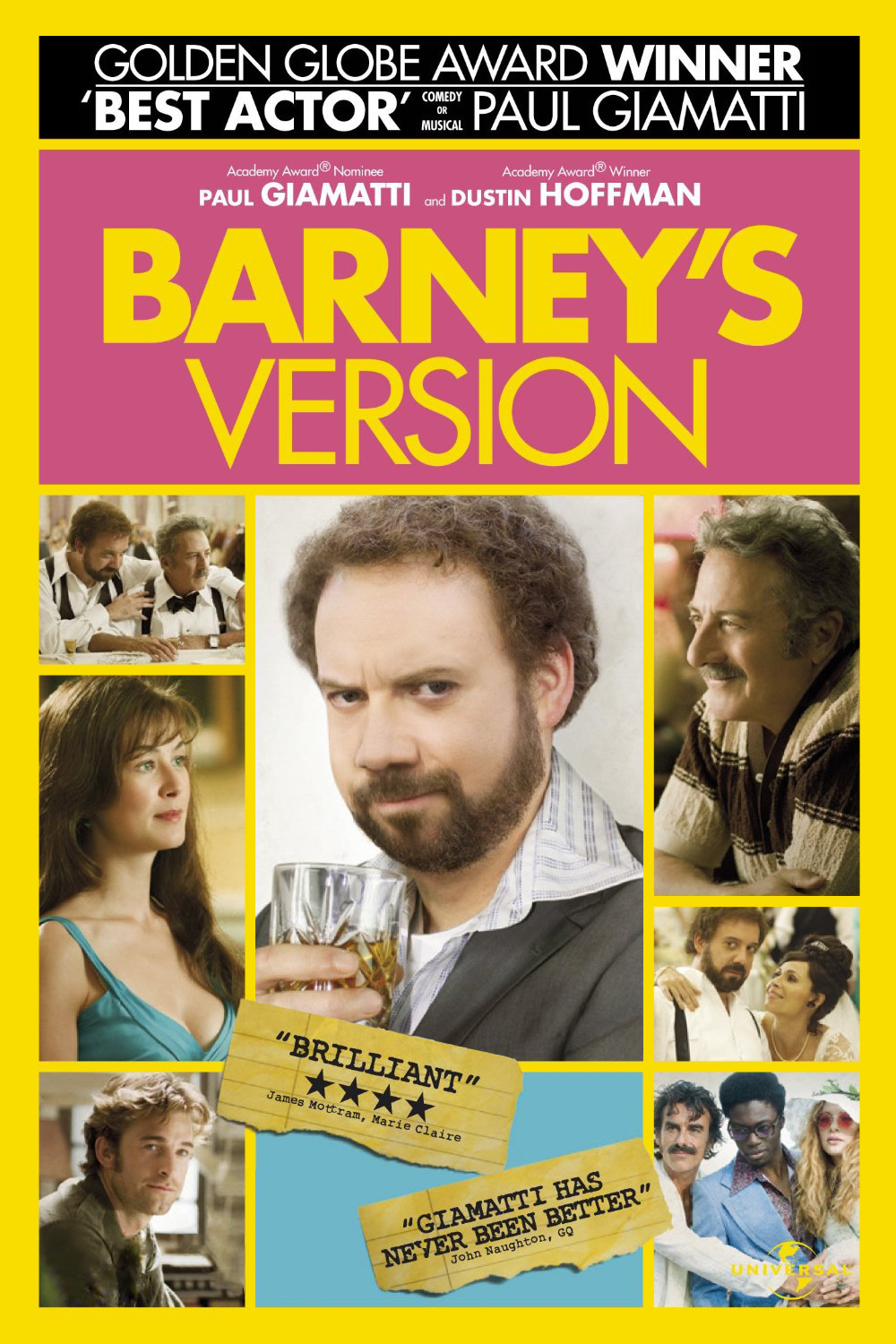

Barney Panofsky is played by Paul Giamatti, who just won a Golden Globe for his performance. It is successful not simply because of his acting but because of his exuding. He has a sweet quality that just barely allows us to understand why three women, the last of them a saint, would want to marry him. It’s not money: He’s broke when he marries the first, the second is rich in her own right, and the third is so desirable that Barney actually walks out of his own wedding reception to chase her to the train station and declare his love at first sight.

“Barney’s Version” is based on a 1997 novel by Mordecai Richler, whose The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1959) is also the life story of a flawed but lovable Jewish character from Montreal. Barney’s story is told in retrospect, in the form of a response to a book written by a cop who is convinced Barney murdered his best friend. How the friend probably did die is suggested in a nicely handled late scene that Barney himself, by the time he experiences it, is not able to understand.

Having once in middle age forgotten where he parked his car, Barney progresses rather rapidly into Alzheimer’s, although most of the film involves scenes before that happens. Since this isn’t a movie about the disease, we might ask why it’s included at all, but I think it functions as a final act in a life that was itself forgettable. Nothing distinguishes Barney, except his romanticism and the woman who inspires it.

She is Miriam (Rosamund Pike), an ethereal beauty with a melodious voice and a patience with Barney that surpasses all understanding. They have two children, they live happily, Barney remains a mess, and at important moments in her career, he would rather be getting drunk in a bar while watching hockey than being there for her. Yet he cannot live without her, and when she goes to New York for a week he becomes reckless with loneliness.

I haven’t read the much-loved novel by Richler, which is told in Barney’s voice and has been compared by some to Saul Bellow’s Herzog. The novel is said to be richer and more complex than the movie, but having only seen the movie, I can respond favorably to what it does achieve.

Giamatti’s performance is one of those achievements. He is making a career of playing unremarkable but memorable men; remember his failed wine lover in “Sideways,” his schleppy Harvey Pekar in “American Splendor” and his soul-transplant victim in “Cold Souls.” (What he plans in his announced project “Bubba Nosferatu: Curse of the She-Vampires” is a question worthy of consideration.) Giamatti’s Barney is not especially smart or talented or good-looking, but he is especially there — a presence with a great depth of need that apparently appeals to the lovely Miriam. She’s one of those women who seems unaware that everyone must constantly be asking, “What does she see in him?” That women persist in seeing things in us, as men we must be grateful.

Dustin Hoffman is very good here as Barney’s father, a retired Montreal detective who imparts wisdom, but not too excessively, and love, but not too smarmily. The bond between elderly father and aging son is cemented by good cigars, which I have seen work in other cases. There is a lot of truth in “Barney’s Version.” It is a mercy that Barney cannot see most of it.