Who is harder to portray in a movie than a writer? The standard portrait is familiar: The shabby room, the typewriter, the bottle, the cigarettes, the crazy neighbors, the nickel cup of coffee, the smoldering sexuality of the woman who comes into his life. Robert Towne’s “Ask the Dust” is not the first film to evoke this vision of a writer’s life, and not the first to find that typing is not a cinematic activity. Just last week “Winter Passing” starred Ed Harris in a version of the same kind of character at the other end of his career.

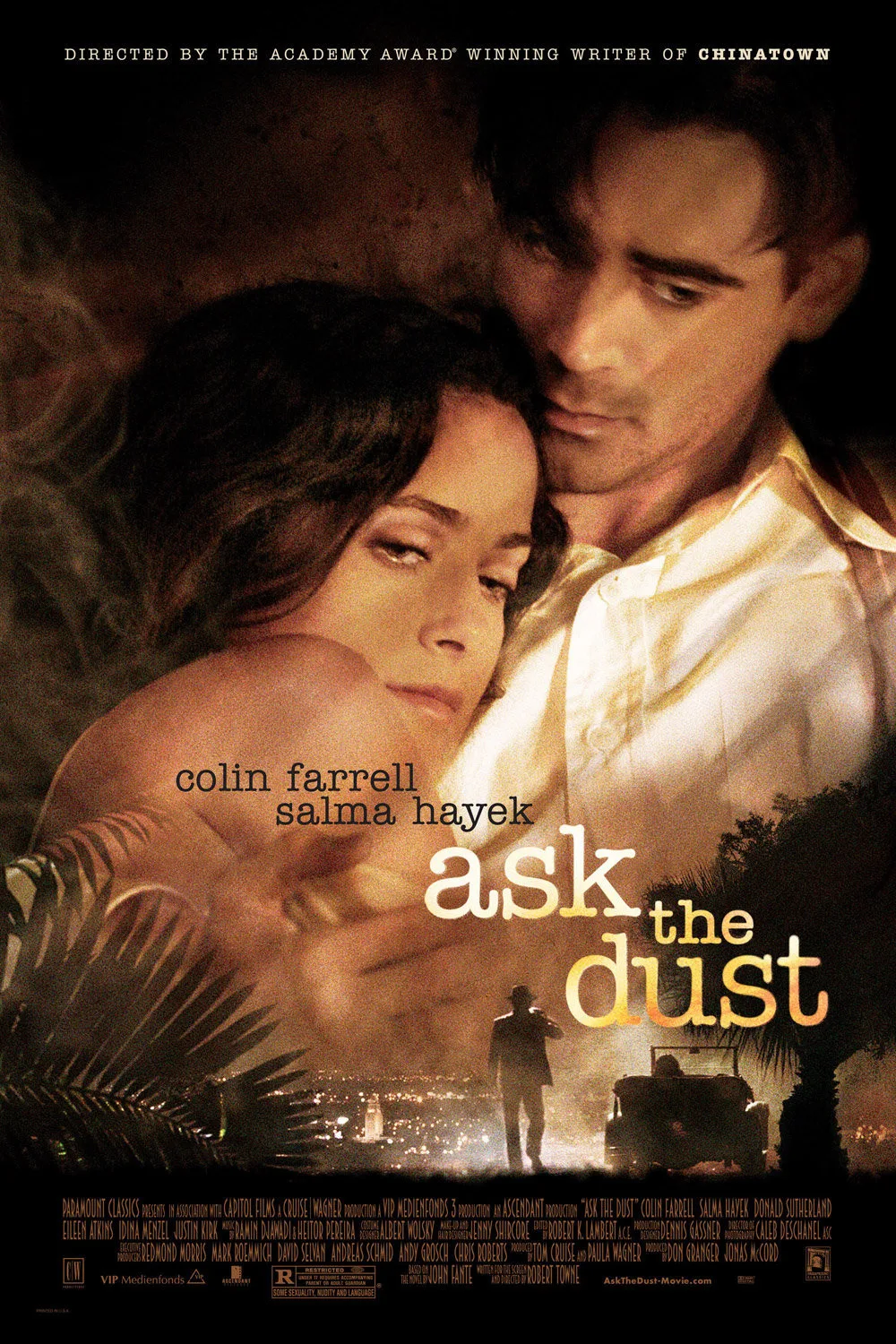

Still, in its wider focus, “Ask the Dust” finds a kind of poetry, because although we may not find it noble and romantic to sit alone in a room, broke and hung over and dreaming of glory, a writer can, and must. The film stars Colin Farrell as Arturo Bandini, who lives in a Los Angeles rooming house during the Depression. He has sold one story to the American Mercury, edited by H. L. Mencken, the god of American letters, and now he tries to write more: “The greatest man in America — do you want to let him down?”

Arturo has one nickel, with which he buys a cup of coffee in a diner where Camilla (Salma Hayek) is the waitress. Something happens between them, but it is expressed curiously. One day she gives him a free beer, which he pours into a spittoon. She takes the magazine with his story, tears it up, and throws it into the same spittoon. Why this hostility, which is meant to mask lust but seems gratuitous?

The answer may be in the source of the material. Ask the Dust is a novel by John Fante, a writer of the generation just before Charles Bukowski, who saw to it that the book was reissued by his publisher, the Black Sparrow Press. It shares Bukowski’s view of women who are attracted to a courtship consisting largely of hostility. In “Ask the Dust,” there is the additional element of racism; Camilla is wounded, as she should be, by prejudice against Mexicans in the city, and Bandini is uneasy about his Italian heritage. When they go to the movies together, Anglos pointedly move away from them, but the movie evokes racism without really engaging it, and the crucial scenes in their romance take place in a cottage on a deserted Laguna Beach, where they create a world of their own. There is also the mysterious Jewish woman Vera (Idina Menzel), who comes into his life, makes a sudden and deep impression, reveals to him her scarred body, and then departs from the plot in a particularly Los Angeles sort of way.

What the movie is about, above all, is the bittersweet solitude of the would-be great writer. Whether Arturo will become the next Hemingway (or Fante, or Bukowski) is uncertain, but Farrell shows him as a young man capable of playing the role should he win it. He could also possibly live a long and happy life with Camilla, but stories like this exist in the short run, and are about problems, not solutions.

I did not feel a strong chemistry between Farrell and Hayek, but I have started to write the word “chemistry” with growing doubts. What is it, anyway? William Hurt and Kathleen Turner had it in “Body Heat,” and Nicolas Cage and Cher in “Moonstruck,” but “Ask the Dust” does not provide a setting for great dramatic towering lust and love: It is about poverty, fatigue, lives that are young but already old in discouragement. Perhaps what we are meant to feel between Arturo and Camilla is not chemistry but geometry: They could fit well together, and provide each other’s missing angles.

I enjoyed and admired the film without being grabbed or shaken by it. Where can such a story lead? I have been lucky enough to know a great writer in his shabby apartment, with his typewriter, his bottle and his cigarettes, and I know he had a famous romance, and that later he hated the woman, and having achieved all possible success was perhaps not as happy as when it was still before him.

What immediately impressed me about “Ask the Dust” was its evocation of time and place. The cinematographer Caleb Deschanel creates Depression-era Los Angeles with the same love the 2005 “King Kong” lavished on New York at the same period, and although one is a smaller film about a writer and the other is an epic about an ape, the cityscapes are so evocative they take on a character of their own. In the case of “King Kong,” much of the city was special effects; in “Ask the Dust” there are some effects but Deschanel in large part is working with reality.

Towne filmed on location in Cape Town, a city I lived in for a year, and I agree with him that it can double for prewar Los Angeles. Just keep Table Mountain out of the shot, and you have storefront cafes, rooming houses built on hillsides with the front door on the top floor, palm trees, and a feeling in some neighborhoods of strangers who don’t know what brought them together or why they wait. Such a person is Hellfrick (Donald Sutherland), Arturo’s wise, weary neighbor, who shuffles onstage to provide the ghost of Arturo’s possible future.

“Ask the Dust” requires an audience with a special love for film noir, with a feeling for the loneliness and misery of the writer, and with an understanding that any woman he meets will be beautiful. Such stories are never about understanding landladies. I am not sure the film achieves great things, but it achieves its smaller things perfectly.