King Mongkut of Siam and Anna Leonowens, the English schoolmarm who tries to civilize him, make up one of the most dubious odd couples in pop culture. Here is a man with 23 wives and 42 concubines, who allows one of his women and her lover to be put to death for exchanging a letter, and yet is seen as basically a good-hearted chap. And here is Anna, who spends her days in flirtation with the king, but won’t sleep with him because–well, because he isn’t white, I guess. Certainly not because he has countless other wives and is a murderer.

Why is she so attracted to the king in the first place? Henry Kissinger has helpfully explained that power is the ultimate aphrodisiac, and Mongkut has it–in Siam, anyway. Why is he attracted to her? Because she stands up to him and even tells him off. Inside every sadist is a masochist, cringing to taste his own medicine.

The unwholesome undercurrents of the story of Anna and the king of Siam have nagged at me for years, through many ordeals of sitting through the stage and screen versions of “The King And I,” which is surely the most cheerless of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musicals. The story is not intended to be thought about. It is an exotic escapist entertainment for matinee ladies, who can fantasize about sex with that intriguing bald monster and indulge their harem fantasies. There is no reason for any man to ever see the play.

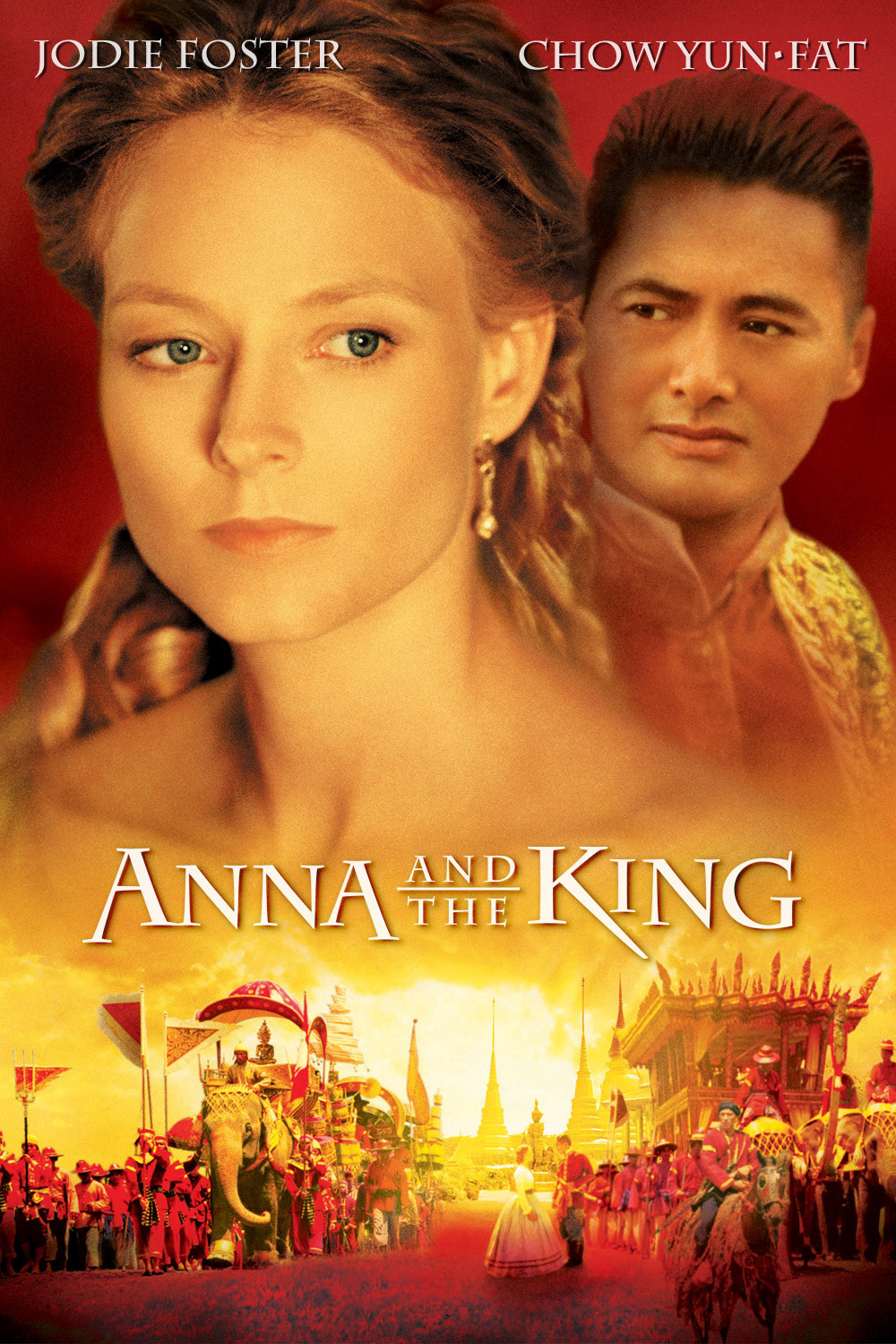

Now here is a straight dramatic version of the material, named “Anna and the King,” starring Jodie Foster opposite the Hong Kong action star Chow Yun-Fat. It is long and mostly told in the same flat monotone, but has one enormous advantage over the musical: It does not contain “I Whistle a Happy Tune.” The screenplay has other wise improvements on the source material. The king, for example, says “and so on and on” only once, and “et cetera” not at all. And there is only one occasion when he tells Anna her head cannot be higher than his. Productions of the musical belabor this last point so painfully they should be staged in front of one of those police lineups with feet and inches marked on it.

Jodie Foster’s performance projects a strange aura. Here is an actress meant to play a woman who is in love, and she seems subtly uncomfortable with that fate. I think I know why. Foster is not only a wonderful actor but an intelligent one–one of our smartest. There are few things harder for an actor to do than play beneath their intelligence. Oh, they can play dumb people who are supposed to be dumb. But it is almost impossible to play a dumb person who is supposed to be smart, and that’s what she has to do as Anna.

She arrives in Siam, a widow with a young boy, and finds herself in the realm of this egotistical sexual monster with a palace full of women. Yes, he is charming; Hitler is said to have been charming, and so, of course, was Hannibal Lecter. She must try to educate the king’s children (68, I think I heard) and at the same time civilize him by the British standards of the time, which were racist, imperialist and jingoistic, but frowned on Siamese practices such as chaining women for weeks outside the palace gates.

By the end of the movie, she has danced with the king a couple of times, come tantalizing close to kissing him and civilized him a little, although he has not sold off his concubines. She now has memories that she can write in her journal for Rogers and Hammerstein to plunder on Broadway, which never tires of romance novels set to music.

Foster, I believe, sees right through this material and out the other side, and doesn’t believe in a bit of it. At times we aren’t looking at a 19th century schoolmarm, but a modern woman biting her tongue. Chow Yun-Fat is good enough as the king and certainly less self-satisfied than Yul Brynner. There is a touching role for Bai Ling, as Tuptim, the beautiful girl who is given to the king as a bribe by her venal father, a tea merchant. She loves another, and that is fatal for them both. There is also the usual nonsense about the plot against the throne, which here causes Anna, the king and the court to make an elaborate journey by elephant so that the king can pull off a military trick I doubt would be convincing even in a Looney Tunes cartoon.

Credits at the end tell us Mongkut and his son, educated by Anna, led their country into the 20th century, established democracy (up to a point) and so on. No mention is made of Bangkok’s role as a world center of sex tourism, which also of course carries on traditions established by the good king.