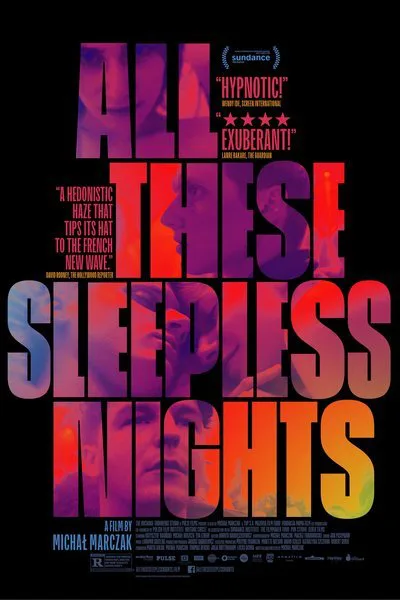

Michal Marczak’s “All These Sleepless Nights” raises about a hundred questions, each more interesting and potentially troubling than the last. For that, at least, we can be grateful. So few films ask anything of their audience, let alone anything as pressing about the nature of fiction and reality. It’s important to state up front that, objectively speaking, “All These Sleepless Nights” is a fascinating work and the thorny edges that will stick to you after its concluded are point enough. The film need not exist for any greater purpose than to raise said questions. The nagging question is whether or not the film stands tall on aesthetic or moral grounds, divorced of its purpose as a conversation piece. Put in a less confusing and circuitous fashion: if this movie were fiction instead of documentary, would anyone care?

The plot can be summed up thusly: Three Polish twenty-somethings go to an endless series of parties, fall in and out of love, and make each other jealous. The story is a more general, ephemeral question of modern youth, sex, drugs and romance. Whether the aesthetics strike your fancy will determine your patience with these three and the milieu of non-stop decadence they occupy. The steadicam-based shooting and cut-heavy editing are on loan from Terrence Malick, who uses it to divine more interesting truths about the soul than are unearthed here.

Marczak’s certainly got one hell of an eye—nary a minute goes by when he isn’t producing some new, formally thrilling image or montage of his heroes in transit, unglued from traditional morality and ritual—but his tricks are nothing new. Indeed, between Malick’s “Song to Song” and Bertrand Bonello’s soon-to-be-released “Nocturama,” about a gang of young terrorists running amok in Paris, there isn’t much that “All These Sleepless Nights” has to offer, thematically or formally, that you won’t see elsewhere in cinemas this year. There are instances where the intensity breaks through the morass of expected taboo courting, as in a thrilling backyard dance party the three youths hold one evening, or a sudden cut to one of them alone on a snowy street, but questions gnaw incessantly throughout. Is all this worth it? What are we learning? What was Marczak out to achieve?

If the film’s grammar is meant to ape fictional filmmaking, which isn’t necessarily true, what is the point? To prove that fiction and non-fiction can share a common tongue. Fine, but wouldn’t it have been better to pick a subject more intrinsically about the line separating reality from fiction? There is nothing in “All These Sleepless Nights” that a screenwriter couldn’t have guessed kids were getting up to. And while it’s certainly transfixing in a queasy sort of way that these kids almost never look at Marczak’s camera during the hundreds of hours of footage that must have been shot to capture this period in the lives of our three ne’er-do-wells, it doesn’t prove anything beyond the fact that milllenials are so used to cameras being thrust in their face that performance is built into their everyday lives. They perform every action as if they were movie characters anyway but thanks to social media and Reality TV, we know that most people live their lives this way, regardless. This is no longer a new idea, and it does not matter whether the film’s moments of spontaneity are staged or not—the kids’ behavior is what you’d expect from either an overwritten teen issue melodrama or a documentary about kids partying. It just appears new thanks to the Malick-derived camera work, which, admittedly is nothing to balk at.

The film is routinely gorgeous, but by turning its “real” people into Malick-style characters, it erodes their humanity in an uncomfortable way. When the film switches to cell phone footage apparently taken by the kids, and heavily featuring the lead female’s naked body, it’s crossing a privacy threshold that Marczak hasn’t reckoned with in any form. When he slickly edits the same girl singing and dancing in her apartment, he’s building a cinematic fantasy around her, using audience expectations of what scenes like this are supposed to achieve emotionally. When he shows her naked, he’s turning her into a fantasy object for the audience’s pleasure. The film veers quickly from Malick to Gaspar Noe, and that is never a good thing. Marczak believes there’s still a kind of intimate charge to be mined from watching teens snort cocaine and get naked, something that’s been halting artistic conversations for pointless moral ones almost as long as cinema itself has been around. Maybe there’s value beyond the film’s formal immediacy, but it would take patience with the kind of aimless bad behavior that was boring back when Larry Clark discovered it to hang around and unpack it. The images cry out to be placed in David Ehrlich’s end of the year countdown video, insouciant and “bold,” and defiant of what it imagines conventions to be, happy to have filmed moments of adolescent bonding as if it had dreamt them up, instead of capturing them in the wild. The film opens with our de facto hero saying that if you watched your life sped up after you’d lived it, you’d be subjected to four days of fireworks, two years of boredom and two weeks of eating potato chips. Cutting from one unchaperoned bacchanal to another may seem like a way to skirt the boredom and snack food, but it’s no way to hide a lack of thematic imagination. That’s the problem with sleepless nights—you stop dreaming.