I know a novel that begins: “This is the saddest story I have ever heard.” Now here is one of the saddest movies I have ever seen, “Albert Nobbs.” It is sad because a woman has chosen to lead her life in a way that is fearful and unnatural to her and must live every moment in dread.

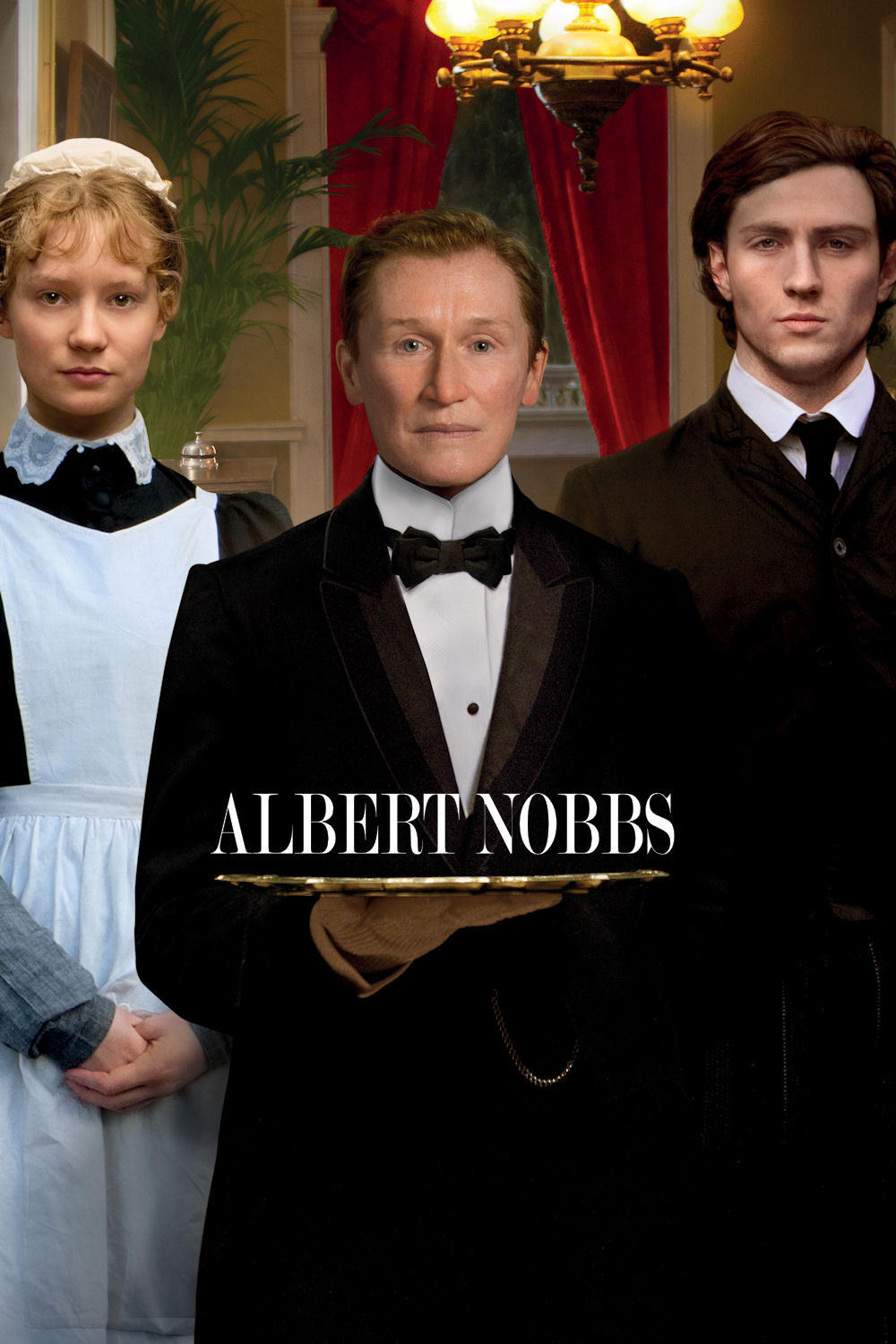

As you must know by now, Albert Nobbs (Glenn Close in an Oscar-nominated turn) is not a man. She works as a butler and waiter in a 19th century Dublin hotel, where she dresses and passes as a man because a woman would not be hired for the job, and she needs the economic security. We can sympathize. But the pain she lives in isn’t worth the money. Many people pass as members of the other sex for many reasons, but my impression is that for most of them, it answers a genuine emotional need.

Albert Nobbs isn’t happy being a man. I don’t believe she’s ever happy at all. There is something stiff and genderless about her, and we suspect she has no sexual experience and desires none. Her entire life is focused on economic security, and she lives in terror of being exposed. Regard her body language: shy, repressed, reclusive, trying to fade in and become invisible.

The hotel is a Dublin crossroads for people of some means but no great distinction. It’s run by the ebullient Mrs. Baker (Pauline Collins), who sails a jolly ship but as an employer is no paragon. Employees come and go, and although Albert is considered by everyone an odd fellow, she’s still there. Homosexuality is not unknown in this establishment; Viscount Yarrell (Jonathan Rhys Meyers) checks in with a free-drinking crew and specifies an adjoining room for his friend. But Albert Nobbs isn’t a homosexual of any description; life would be simpler if she were.

One day, Hubert Page (Janet McTeer) arrives to do some house painting. Hubert is tall, lanky, smokes a lot, kids around, and is obviously (to our eyes) a woman. She gets by on personality and nerve. She quickly reads Albert, and in what must be the most astonishing moment of Albert’s life to date, exposes her breasts and shares her secret. I wonder if that was the first time Albert realized she wasn’t the only person who has ever passed for another sex.

That opens the film’s only scenes that give us some reason to hope for Albert. The two women spend a liberating day on the beach, and Hubert takes Albert home to her wife, Cathleen (played by Bronagh Gallagher with quiet calm and tact). It becomes clear, if it wasn’t already, that Albert has only a sketchy idea of what men and women do with each other, what sex is, what marriage is.

But she has a dream. She has her eye on a storefront that she believes would make a nice little tobacco shop. There would be a room in the back where tea would be served. And a room upstairs to, well, to share with a “wife.” In an exercise of dismaying naivete, she imagines Helen (Mia Wasikowska), a young housemaid at the hotel, in this role. For Albert, it involves a business partnership, not a romance.

This is such a brave performance by Glenn Close, who in making Albert so real, makes the character as pathetic and unlikable as she must have been in life. The film is based on a story by George Moore (1852-1933), an Irish realist writer who may have known some real-life parallels in Dublin. Close starred in an Off-Broadway production of a play based on it in 1982, and tried ever after to make it a film. The Hungarian director Istvan Szabo was attached to the project circa 2001, but now the film has been made with Rodrigo Garcia, whose sure touch with women characters can be seen in his “Nine Lives” and “Mother and Child.”

Close never steps wrong, never breaks reality. My heart went out to Albert Nobbs, the depth of whose fears are unimaginable. But it is Janet McTeer who brings the film such happiness and life as it has, because the tragedy of Albert Nobbs is that there can be no happiness in her life. The conditions she has chosen make it impossible.