“A Woman Is a Woman” was Jean-Luc Godard’s second feature, made in 1961 close on the heels of “Breathless” (1960). “It was my first real film,” he has said, but a statement by Godard is always suspect and in this case is plain wrong: “Breathless” was his first real film, a masterpiece, and “A Woman Is a Woman” is slight and sometimes wearisome.

The movie stars Godard’s wife, Anna Karina, who was to achieve her own greatness in his next film, the wonderful “My Life to Live.” Here she plays a completely improbable character, a stripper who comes home to her yuppie boyfriend and tells him she wants a baby. Surely no strip club in movie history has been more genteel and less sleazy than the one she works in, where the women walk idly up and down between rows of tables where clients smoke, and look, and nurse their drinks. Their five-minute stint over, the girls say goodbye all around and return to the street, free spirits.

Angela Recamier is her name, and Jean-Claude Brialy plays Emile Recamier, but the movie strongly suggests they are not married. Nor does Emile want a baby, although his friend Alfred Lubitsch (Jean-Paul Belmondo) would be happy to impregnate her. Naming the Belmondo character after Lubitsch is one of the movie’s countless cinematic in-jokes; there is even a moment when Belmondo runs into Jeanne Moreau and asks her, “How is ‘Jules and Jim’ coming along?” And another where he smiles broadly at the camera, in tribute both to Burt Lancaster and to the fact that he did the same thing in “Breathless.” The movie, which comes advertised as Godard’s tribute to the Hollywood musical, is not a musical, and indeed treats music with some contempt, filling the sound track with brief bursts of music that resemble traditional movie scoring, but then interrupting them arbitrarily. It contains other moments designed to suggest the director calling attention to his control of his materials, including the device of having the same couple kissing in a street alcove in shot after shot.

There is, although, one sequence showing the mastery of technique by Godard and his editor, Agnes Guillemot. Angela is shown a photograph that Alfred claims shows Emile cheating on her with another woman. As she studies the photo, the movie cuts from her face to his face to the photo, and then again and again. Sometimes there is a little dialogue. The photo keeps reappearing on the screen. The effect is to suggest the way she becomes obsessed with the hurtful image and can’t stop thinking about it, and as a visual evocation of jealousy, it’s kind of brilliant.

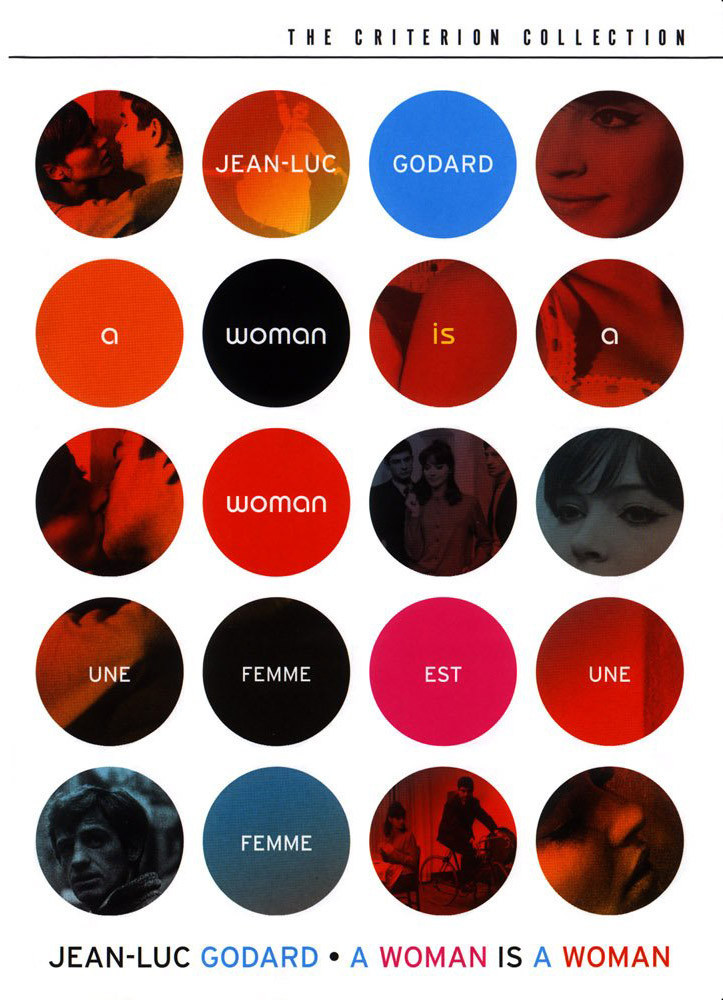

But the film itself, at 84 minutes, is overlong, a minor chapter in an early career. It has been carefully restored for this theatrical re-release, and the print showcases the wide-screen cinematography of Raoul Coutard, and we can see here stylistic choices that would become omnipresent in the films to come: The use of big printed words on the screen, the use of bold basic colors, and the use of books as objects which embody their titles (in one cute moment, Angela and Emile aren’t speaking, and hold up books with titles that indicate what they want to say). The movie is bright and lively, but too precious, and Godard would soon make much better ones.

Ebert writes about “Breathless” and “My Life to Live” online in the Great Movies series at www.suntimes.com/ebert.