“A Vigilante,” which stars Olivia Wilde as a domestic abuse survivor who remakes herself as an avenging angel, is one of those small but brutal films that major directorial careers are made from. Every frame of it feels measured and thoughtful, even when the camera gets so close to its heroine’s pain and rage that just looking at her is an uncomfortable experience. Written and directed by first-time feature filmmaker Sarah Daggar-Nickson, it’s a movie-as-weapon. The evident smallness of the production belies its power to disturb. It’s like one of those knives that are small enough to be hidden in a coat sleeve or the lip of a boot but that can still cut a man’s throat.

And in this film, the recipient of violence would definitely be male. A feminist revenge thriller in the spirit of “Ms. 45,” “Enough,” and 2017’s bluntly titled “Revenge,” this is a film about societally tamped-down rage over mistreatment and abuse finally welling up and exploding in the faces of men who lord their superior physical strength and patriarchal authority over women and children.

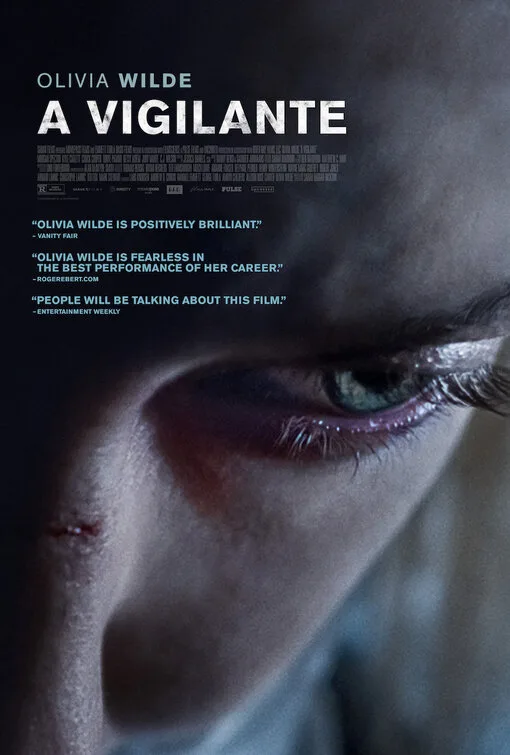

The movie begins with a sequence that could well be the premise-establishing prelude to a TV series like the original “The Equalizer“: following a sequence of shots establishing a bleak midwinter setting, the heroine, Wilde’s Sadie, is seen working a punching bag, the camera so tight on her face and upper torso that the swinging motion of her fists makes the viewer feel battered. Then it moves into a “mission,” with Sadie visiting the home of a man who’s abusing his wife and child, beating him to a pulp (much to his surprise; he thought he’d be able to incapacitate her with one blow) and then ordering him to turn over most of his money to his wife and leave their lives forever.

Obviously, not only is Sadie’s approach not an emotionally, socially or legally acceptable way to handle that kind of situation, it’s probably unrealistic, but no more so than a scenario in “The Equalizer” or “The Punisher” or one of those grungy private eye films where the hardboiled hero shows up in the home of a very bad man and quietly tells him how things are going to be from now on.

But one of the things that distinguishes “A Vigilante” from other vigilante films is its interest in the physical effects of violence (the aftermath in particular), and the toll that Sadie suffers both as a domestic abuse survivor and as someone who has committed to doing more violence order to better the lives of fellow victims and assuage her own feelings of thwarted justice. Sadie’s husband—who is played by Morgan Spector, but is such a loathsome figure that the film refuses to name him—has committed even more unspeakable acts than you might imagine from reading this piece. He’s the movie’s Big Bad, he’s still out there somewhere, and as soon as the film reveals this (fairly early), you start imagining a confrontation that “A Vigilante,” in its proud pulpiness, isn’t about to deny you.

“A Vigilante” is upfront about being a cathartic fantasy, starring a conventionally beautiful and physically fit star who could play a superhero (and sort of already is playing one here, when you think about it; put a cool costume on her and you’ve got a female Frank Castle). The only thing I can say against it is that it doesn’t seem to have fully thought through the implications of reveling in fantasies of payback and control while also going out of its way to emphasize the real-world impact of Sadie’s suffering and the brutality she visits on (deserving) others. The gold standard for this kind of movie—recently, anyway—is writer-director Lynne Ramsay’s “You Were Never Really Here,” which also verged on turning into a Batman movie sometimes, but offered a slightly more nuanced take on the story of a PTSD-suffering, lethally skilled loner moving through a twilight world of crime and violence. It’s a badass movie that remembers that it’s not supposed to feel badass but can’t always resist the urge and might not be able to resist it, given the kind of film that it is. All of its characters except Sadie are psychologically rather thin, existing mainly as satellites orbiting around the North Star of its heroine’s fury. But this, too, ultimately feels like an equalizing impulse. If an inability to avoid getting high on your own supply were a deal breaker in vigilante cinema, there wouldn’t be any vigilante movies. Ditto the tendency to favor the main character’s issues over everyone else’s.

And it’s also important to note here that, although we’ve seen a number of movies over the decades putting the spotlight on female avengers, such films are still comparatively rare, whereas similar stories about men could fill up very fat reference books. And the movies starring women (whether directed by women or men) tend to be more aware of the ironies, contradictions and inconsistencies embedded into the very idea of a revenge fantasy than a lot of films starring, say, Clint Eastwood, whose vengeance-driven thrillers are suffused in disgust and regret but (when they starred Clint, anyway) made sure to make the hero look as mythologically awesome as possible while doing things that theoretically poisoned his soul. “A Vigilante” spends more time showing the debilitating psychological impact of violence, both on Sadie and on the families she’s trying to help, than almost any revenge thriller I can think of.

And Wilde’s performance is so committed that there are times when you may fear for her physical safety and emotional health. It’s not just the bruising scenes of fighting and torture that unnerve, it’s the many protracted scenes of Sadie weeping over her personal losses, runny-nosed, red-faced, at times nearly hyperventilating at the unfairness of it all. This is a raw performance that sometimes steers close to psychological self-mutilation. If a male star gave it, we’d already be talking not just about whether it was prize-worthy, but how many it should get.