In a small town near Nottingham, England, two young teenage friends live next door to one another, and get along like all teenage friends do–which is to say, weirdly, with long silences that have no reason, followed by business as usual.

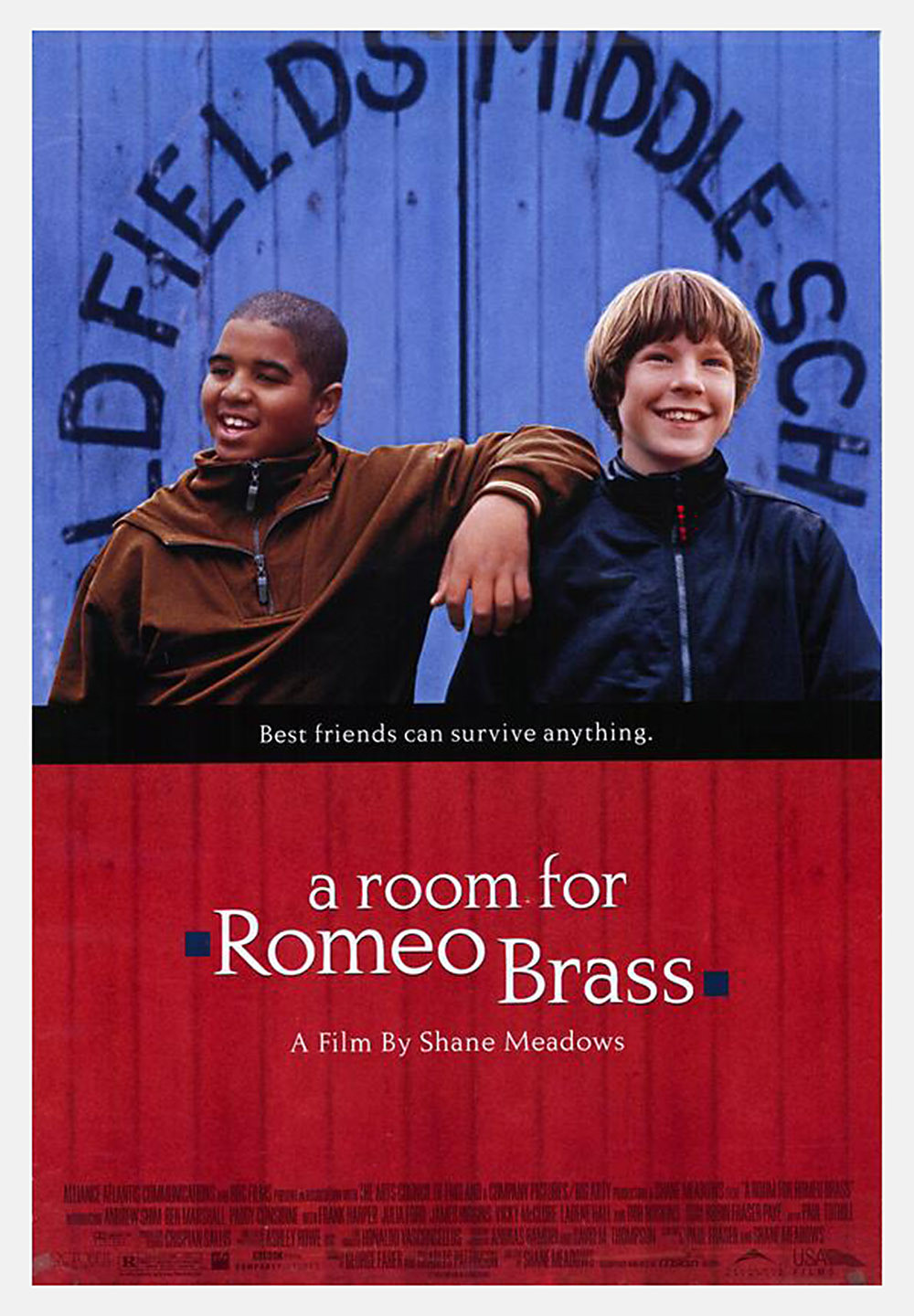

Romeo Brass (Andrew Shim), the pudgy, optimistic son of a black mother and an absent white father, is not the lad to send to the fish and chips shop if you expect to find any chips left in the bag when he gets home. Gavin Woolley (Ben Marshall), nicknamed Knocks, limps from a back disorder, needs surgery, and has a father who would rather watch television than members of his own family. Romeo and Knocks like each other but don’t get carried away by it.

This is Ken Loach country–with its working-class characters from the Midlands–but then a little Mike Leigh creeps in. Knocks, whose limp singles him out, is picked on by some school bullies. Romeo, who was sort of the instigator, tries to help him, but then an adult stranger in a van leaps in and breaks it up. This is Morell (Paddy Considine), well-named after a mushroom since he flourishes in the shady, damp spaces of his own mind. Coming to visit Romeo and his family, he puzzles them with a dramatic account of his battles between himself and an “unseen entity.” Romeo has a sister named Ladine (Vicky McClure), very attractive, stranded in this backwater, and Morell wants to date her. This is not a simple matter, since Morrell is a very peculiar man, unpredictable, erratic, subject to quick shifts of mental weather. At one point Morell actually persuades Romeo to ask his sister out for him, and when Ladine does go on a date, it is more out of boredom and recklessness than any possible interest.

We have by now become familiar with the characters. We kind of understand why, after Knocks comes home from surgery, Romeo doesn’t visit him. Embarrassments grow up between kids without any reason.

Earlier we understood when Romeo didn’t want to stay at home, and Knocks was happy to have him move into his room. Everybody knows everybody’s business in this neighborhood; when Romeo’s mother berates him for not going to see Knocks, Knocks can hear their argument through the thin walls separating their row houses.

Morell is the character who supplies unpredictability and the possibility of danger. And yet he is not simply a stalker or a psycho or any of the other easily categorizable things he might be in a more ordinary movie. He is different every time we see him, and sometimes surprises himself. He can be dangerous, and then suddenly disarm himself. The performance by Paddy Considine is a work of sullen and unpredictable craft; I was reminded of David Thewlis in Mike Leigh’s “Naked.” The film’s climax is logical, I suppose, and yet utterly unanticipated–especially in the way it brings in violence through a marginal character.

“A Room for Romeo Brass” was directed by Shane Meadows, who made “Twentyfourseven” (1998), the movie where Bob Hoskins started a boxing club for disadvantaged lads who were reduced to fighting in the streets. That film felt like it wanted to be a documentary, and here, too, Meadows seems fascinated by the happenings of everyday life. “Romeo Brass” is a better film, effortless in the way it insinuates itself into these families, touching in the way it shows how fiercely Romeo and Knocks are, despite everything, their own little men.