“Tonstant Weader fwowed up.” Dorothy Parker originated that immortal line, in 1928, expressing, under her “The New Yorker” pen name “Constant Reader,” what would turn out to be very much a minority opinion on A.A. Milne’s “The House At Pooh Corner.” It occurred to this reviewer as he attempted to grapple with the oppressive, bloodless, winsome gentility of “5 To 7,” a romantic comedy written and directed by Victor Levin and set in a New York City where its protagonist/narrator tells you in the first five minutes or so, “you’re never more than twenty feet away from someone you know, or someone you’re meant to know.”

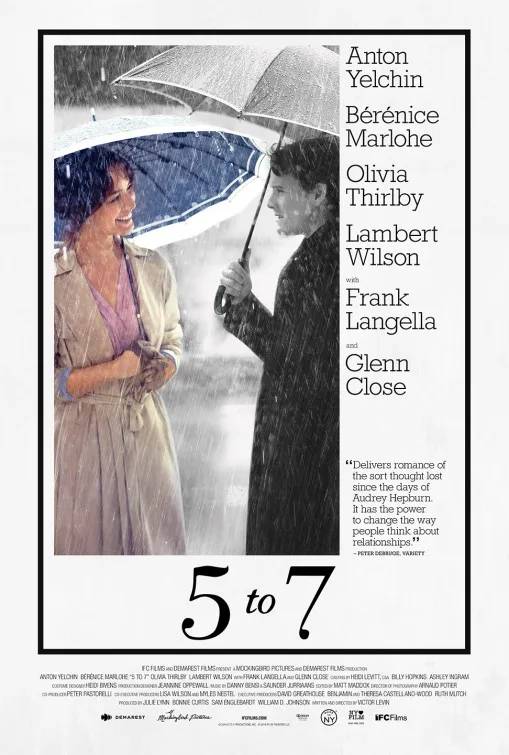

Said protagonist/narrator is a fellow in his 20s named Brian and, as you may have guessed, this motion picture does not depict him taking the subway a whole hell of a lot. Brian, played by Anton Yelchin, is a young wannabe writer whose study wall is festooned with rejection letters—on paper, even—from august publications, but the steady stream of do-not-wants does not stop him from continuing to ply his whatever it is; the fiction editor of “The Atlantic,” Brian tells his mom, said “sorry” in the latest rejection, which to him is a sign of progress. One afternoon while out maybe trying to acquire Life Experience to feed his fiction, Brian meets a most enchanting French woman, Arielle (Bérénice Marlohe), and after getting off to a poorish start with a “Little Mermaid” reference, recovers with some wry in-French banter about how to be a smoker in New York these days is to be a kind of exile, and she mysteriously offers to meet him again between the hours of the film’s title. As it happens, Arielle is married, not unhappily, but it’s just that she’s so French she can take a lover, as her husband has, and while this proposition temporarily affronts Brian’s sense of ethics, he soon gives himself over to a new kind of amour, and why not.

So far, so tolerable, and when Brian and Arielle share a champagne toast in a long, unbroken take in her gorgeous apartment and Arielle responds to one of Brian’s bromides with “Maybe you should write fortune cookies,” so moderately sharp. But somewhere before the halfway point the movie crosses a line, and its fantasy version of New York, not to mention of French women, gets to looking kind of hoary and inadvertently adolescent. Eventually, the fact that the characters are all aware of the multiple clichés they’re uttering—an exchange between Brian and a young editor (Olivia Thirlby) is particularly excruciating in this respect—doesn’t redeem or excuse the clichés.

Writer/director Levin, an old television hand, is clearly looking to make his own “Stolen Kisses”—his Truffaut fandom extends to strategically placing a “Jules And Jim” clip in the movie—but the stupefying level of wish fulfillment here makes the film play, oddly, like a much more refined “Killing Zoe.” Yes, the 1993 movie in which a callow bro played by Eric Stoltz makes a gorgeous French call girl fall madly in love with him in the first ten minutes. Speaking of Stoltz, he appears here, playing an editor named Jonathan Galassi, which is also the name of a very real New York-based book person, and it’s odd that an actor should be playing the role since Levin, who must be very well-connected, persuaded luminaries such as Julian Bond and Daniel Boulud to appear in cameos as themselves.

The oddest cameo is by David Remnick, the real-life editor of the real-life “New Yorker,” appearing as himself and proclaiming Brian’s fiction-writing talents (in case you weren’t able to guess this, his affair with Arielle really agitates his muse, and stuff) to Brian and Brian’s parents (played by Glenn Close and Frank Langella) in a very confusing scene. I wondered whether Remnick had lost a bet at first. I then reflected that in the weirdly rarified world this movie wants to depict, a “New Yorker” editor would not be caught inanimate doing a cameo in any film, let alone one as mediocre as this one, and this paradox set my head a-spin a little bit. But by the time the picture wound down to its finale, with the narration spouting a bunch of unearned platitudes about “perfect love” (as Truffaut knew, and communicated in “Stolen Kisses” and elsewhere, there’s no such thing, and imperfect love is something to be unequivocally treasured) and one of its characters sporting tortoise-shell-rimmed glasses to connote the Passage Of Time, the only thing in my mind was that Dorothy Parker phrase.