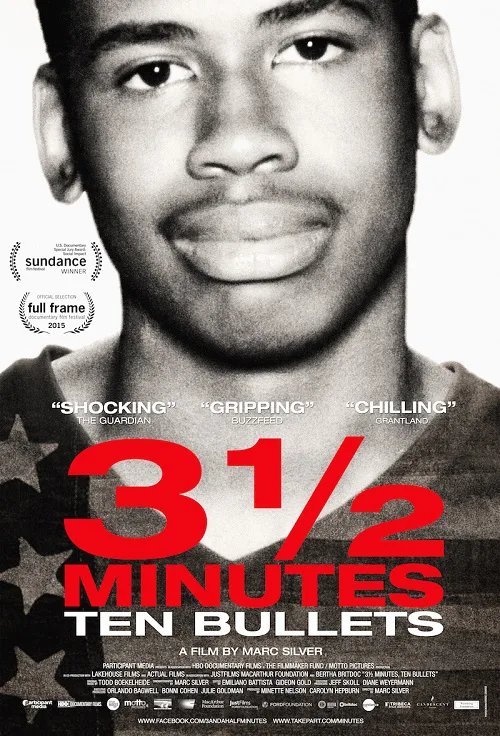

On Friday, November 23, 2012, around 7:30 p.m., a Jacksonville, Florida gas station erupted with gunfire. When the smoke cleared, 17-year old Jordan Davis was dead of gunshot wounds, and the car in which he and his friends had been traveling was riddled with bullet holes. “3 1/2 Minutes, Ten Bullets” is an account of the event and its legal and racial implications. It’s told in a contemplative style that brings the story’s emotions to life without hyping them.

The shooter was Michael Dunn, 45 and white. Davis and his friends—Leland Brunson, Tommie Stornes, and Tevin Thompson—were teenage and black. The altercation started when Dunn and his girlfriend, Rhonda Rouer, stopped at a gas station. They pulled into a parking spot adjacent to the teenagers, who were blasting rap music. Tommie Stornes was already in the store buying gum and cigarettes. Rouer entered the gas station’s convenience store for white wine and chips. On her way inside, she heard Dunn complain about the teenagers’ “thug music”—Dunn later insisted he hadn’t used that word, but had instead called the music “rap crap.” Dunn then asked the teenagers to turn it down. Thompson complied, but then Davis told him to turn the music back up. Dunn said Davis threatened to kill him, opened his car door and pointed what Dunn thought was a shotgun, and Dunn opened fire. But police who searched the vehicle found no evidence of any kind of weapon. Rouer later said that Dunn didn’t say anything to her about a gun until a day later, though Dunn insists he described it to her repeatedly.

Dunn was ultimately convicted of first-degree murder in fall, 2014. An earlier 2014 proceeding found Dunn guilty of second degree murder for shooting at the other teenagers in the car, but jurors could not agree on the first-degree murder charge for killing Davis. Dunn’s legal team invoked Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” law, which allows for the possibility of legally killing another person that the killer believes might pose a lethal threat. Davis’ parents have subsequently called for a repeal of that law as well as tighter restrictions on guns.

This all adds up to as explosive a documentary topic as you’ll ever see.The violence originates in multi-layered resentment—racial, cultural and generational—with “Stand Your Ground,” gun control and machismo stirred into the mix.

Luckily, Marc Silver and his collaborators avoid anything that might seem inflammatory. They explore the case in empathetic, detached images that are carefully composed, and often beautiful in a sad way, and mostly resist the urge to treat people’s suffering as a thing to be photographed. Shots of towering trees, knotted highways and urban southern panoramas squashed beneath blue-grey cloud banks contribute to a sense of spiritual torment.

The documentary favors Davis’ side of the story, partly because Jordan’s parents gave the filmmakers access to their lives and stories, while Dunn, his girlfriend and his family apparently didn’t. (They’re represented in the film mainly through courtroom shots of them testifying and listening to others’ testimony.)

But mostly the movie appears to side with Davis’ parents because Dunn’s story is full of contradictions and holes. He comes off seeming like very bad news even though Silver omits or glosses over details that might have made him even more unsympathetic, such as the fact that he and Rouer left the gas station where Dunn had shot a stranger to death without reporting the incident to the police, then went back to their motel and ordered a pizza.

It’s often said that when you’re presented with conflicting accounts of an event, the one that seems most plausible is probably correct. The movie seems to align itself with that sentiment. There is nothing in the pasts of Davis or his friends to suggest that they would have had a shotgun in the car, which makes Dunn’s insistence that he saw one seem like racist paranoia—an excuse to act out a homicidal fantasy that he might’ve been nursing for years before pulling into that parking spot. The film goes into some detail about how, to quote one of Davis’s friends, “‘thug’ is the new ‘n-word,'” and establishes Dunn as a man with anger management issues that overshadowed his likable qualities.

The most damning testimony, though, comes from Rouer. She could easily have taken Dunn’s side and told authorities that she saw Jordan open the car door and pull a shotgun on her boyfriend (actions that nobody else at the gas station saw), but she says she saw nothing of the kind, and disputes other key points of his account as well, including his insistence that he never used the word “thug” to describe the teenagers’ music. Dunn told authorities that the following morning he called a friend in law enforcement to arrange to talk to police, but Rouer later said that the friend called Dunn, not the other way around, and the two men didn’t talk about the shooting. There are no heroes in this story, but Rouer nearly qualifies. She sided with strangers over her own boyfriend because she thought it was the right thing to do, and when she breaks down on the witness stand, you can see how much the decision cost her.

It all adds up to a portrait of a man who knows he’s done something inexcusably awful and can’t face the consequences. Police interrogation room footage and recorded phone calls contribute to the feeling that Dunn was disconnected from the murder, and cared mainly about his own fate. He’s eerily dry and “rational,” at times lighthearted, when he discusses the shooting with a detective after the event; he talks out various scenarios as if describing a fender-bender. There are moments in the audio where Dunn seems to be as callous and self-serving as his detractors claim, including a bit where he compares himself to “the rape girl that was attacked for wearing skimpy clothes.”

Silver’s documentary occasionally suffers from lack of focus and clarity. There are times when the dreamy mood derails the narrative, and makes it seem as though the film is being swallowed by sadness over the events it’s chronicling. And while the movie’s determination to let us find our way through the story is laudable, onscreen titles might have helped establish where we are, and whom and what we’re looking at. You don’t learn the names of any of the supporting players (including the lawyers) until somebody says them out loud, and unless you’re paying close attention to every word of the TV news stories that Silver samples, you might not know what month or year you’re in, much less which courtroom trial you’re looking at.

There are also moments where you might wish that the mostly superb editing had found a way to shape the events more precisely, to pose questions that the film never asks in so many words, even though it seems to want to. Would a thorough mental-health screening process for gun licenses have prevented Dunn from carrying a handgun? Did anybody ask Dunn why he didn’t immediately turn himself in after killing a stranger? Was Davis’ angry response to Dunn’s request that he turn the music down culturally “general”—a teenage black man/middle-aged white man/rap thing thing—or was it rooted in specific incidents from Jordan’s life? (One of Davis’ friends says Jordan said he was tired of people telling him what to do, but this isn’t followed up.)

These are not deal-breaking flaws, though. “3 1/2 Minutes, Ten Bullets” doesn’t move or look like most documentaries you’ve seen. The movie’s meditative quality makes you feel for everyone involved in this tragedy—even Dunn, who seems very much a prisoner of fear and anger. Where a lot of documentaries would try to stir outrage, this one just leaves you shaking your head. The numb feeling comes from the knowledge that what we’re seeing onscreen—the racial and generational animosity, the normalization of gun violence, the checklist of reasons why nothing can be done—are just pieces of one more American day.