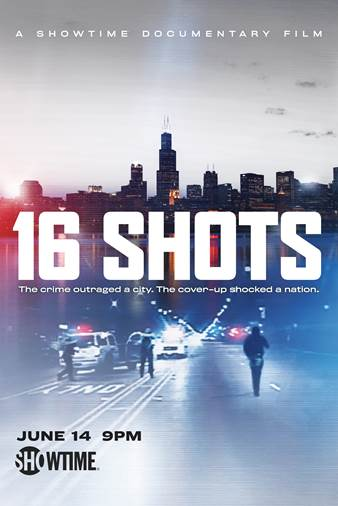

When Chicago Police Officer Jason Van Dyke shot Laquan McDonald 16 times in the middle of the street, he couldn’t have possibly known all of the repercussions. After all, before the smoke had really cleared, all of his colleagues were designing a defense of his actions. Before defenders of the Chicago P.D. come raining down on the comment sections, these statements are indisputable. Van Dyke shot McDonald, who was armed with a knife, and who Van Dyke claimed was charging him with that knife. All of the police officers on the scene used the exact same language in their reports (emphasis on the word “attacking” for what McDonald was doing with his knife and body language) and a few of them went to a nearby Burger King and erased 86 minutes of security camera footage. Eyewitnesses claimed then and now that the officers they spoke to that night pressured them into changing their stories. You can say that Van Dyke and his colleagues realized the incendiary times in which we live in terms of police and civilian relations necessitated these actions to control the narrative of a justified shooting. Or you can use the phrase spoken by then-Mayor Rahm Emanuel and highlighted in Rick Rowley’s “16 Shots,” opening limited today and on Showtime: “Code of silence.”

“16 Shots” isn’t as much about the actual shooting of Laquan McDonald as one might expect. We don’t hear from his family and friends. Instead, it’s about the ripple effect that transformed a city that night. And if you’re not from Chicago, you might think that word choice to be hyperbolic. It is most definitely not. Before the story was even close to over, the Superintendent of the Chicago Police Department (Garry McCarthy) had stepped down and the State’s Attorney (Anita Alvarez)—who did not bring the case forward as people thought she should have—was voted out of office in an electoral upset. Most shockingly, Emanuel chose not to seek re-election, and nearly everyone in Chicago believes that choice was a direct result of the fallout from McDonald’s death.

On October 20, 2014, police responded to reports that a young man was breaking into vehicles in a trucking yard on the South Side of Chicago. One officer spoke to McDonald, and even walked him toward Pulaski, where other officers responded. McDonald reportedly had PCP in his system (toxicology reports would later confirm this) and was waving a knife as he walked down the middle of the street, away from officers. When Officer Van Dyke arrived on the scene around 10pm, he emerged from his vehicle and shot McDonald 16 times in roughly 15 seconds. We know this not because of reports or eyewitness testimony but because of a dash cam video that makes it disturbingly clear. McDonald was walking away and was not “attacking” anyone. When the video hit the public consciousness, the reaction was instant and angry. Protests began, and the aforementioned political ripple effect started happening, and led all the way up to Officer Van Dyke being convicted of murder as well as aggravated battery for all 16 shots.

“16 Shots” is a very deliberate, ominous documentary, filled with views of the Chicago skyline and a pulsing score, but Rowley makes several smart decisions as a storyteller. First, he presents both sides. McCarthy, Van Dyke’s attorney, Alvarez, and a few spokespeople for the FOP are on-hand to defend their actions and further elucidate on the difficulties faced by police officers in the ‘10s. This is an argument that I’ve personally never understood. One can believe that police officers have difficult, dangerous jobs, and also believe that one committed murder. They are not exclusive thoughts. And yet it’s clear that all of Van Dyke’s defenders see an attack on one cop as an attack on all cops. And yet they’re downright offended when the subject of a “Code of Silence” comes up. What’s most amazing is how people can see the video and come out with completely different reactions to it, and Rowley understands that this skewed, protective perception is at the root of so many of the problems between police officers and those they protect. Two people can watch someone be shot 16 times and have completely different reactions. How can we work together when that’s the case?

Most effectively, Rowley imbues his film with a simmering undercurrent of anger. He speaks with activists and community leaders, all of whom express doubt that anything would come of this situation, especially not a conviction of an active police officer. After all, cases like these have come up in the past in other cities and no one who pulled the trigger went to jail. Why would this one be different? And Rowley understands that the main reason this one was different might have come down to luck. One of the attorneys for the McDonald family expresses surprise that his subpoena for the video worked, wondering if whomever was in charge that day really knew what they were sending. If that dash cam video doesn’t get out, it’s very likely that this case never gets national attention.

But it did get out. And “16 Shots” feels like an impassioned, intelligent document of a major moment in the history of Chicago. Since the McDonald case, there have been signs of improvement in terms of crime and police relations in my hometown. What people like McCarthy—who can’t finish a thought without reminding you how difficult it is to be a cop nowadays—never seem to understand is that those of us who want justice for McDonald also want police officers to be safe and effective. Blanket condemnation of all police officers is as damaging as believing men in blue can never do wrong. Van Dyke is in jail (although for nowhere near as long as the jury that convicted him believed he should be), and a lot of the major players involved in the case are out of power. The question all of us, on both sides, need to ask ourselves is—what now?