It seems wrong to say that Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger “passed away” at age 74. Let’s respect the man’s vision and avoid euphemisms. Say that he died and that his remains will merge with infinity.

Giger was a painter, sculptor, graphic artist and production designer. He was best known for designing the titular creature of the “Alien” films, a “xenomorph” that began life as a leathery egg which then disgorged a “facehugger” that attached itself to, well, a face, and then inserted a tube into the victim’s mouth which laid another egg in the host’s stomach that grew into creature that looked like an eyeless snake with serrated teeth which finally burst from the victim’s body like a huge maggot eating through dead flesh (sorry if you’re reading this as you eat, but if you’re eating, why read an appreciation of H.R. Giger?) and went off to make its way in the world, getting larger and more hideous.

More than one observer has pointed out that almost nothing about the “Alien” creature makes biological/evolutionary sense. The process seems wasteful: so many steps! I thought this even as a child, sneaking surreptitious peeks at the 1979 comic adaptation of the film in bookstores and hoping that my parents didn’t see me and reprimand me.

And yet the very counterintuitive strangeness of the creature (a collaboration between Giger, screenwriters Dan O'Bannon and Ronald Shusett and director Ridley Scott) worked for the original 1979 film, and the sequels that adapted Giger’s designs to suit their own purposes. The films were nightmares. The creature that dominated them was a nightmare creature—an amalgamation of Freudian and Jungian terror. In its final form it looked like a bipedal insect (silvery in the first film, black in the sequels) and had an eyeless, banana-shaped head that simultaneously suggested an oil derrick, a rock hammer and a dildo. It was invasive, assaultive, enfolding and mysterious, a Bad Mommy and Bad Daddy, a demon rapist boogeyman looking to impregnate the universe.

It was as if somebody had taken the ichthyologist Hooper’s description of the Great White in “Jaws” and turned it into a space beast: “A perfect engine, an eating machine that is a miracle of evolution – it swims and eats and makes little baby sharks, that’s all.” As Ash, the Nostromo‘s science officer and secret android/company man, put it: “I admire its purity. A survivor… unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality.”

“In the first design for the alien, he had big black eyes,” Giger said in a 1979 interview. “But somebody said he looked too much like a—What do you call it?—a Hell’s Angel; all in black with the black goggles. And then I thought: It would be even more frightening if there are no eyes! We made him blind! Then when the camera comes close, you see only the holes of the skull. Now that’s really frightening. Because, you see, even without eyes he always knows exactly where his victims are, and he attacks directly, suddenly, unerringly. Like a striking snake. “

Giger knew what scared us. He always did.

And he was ahead of the cultural curve in ways that only true artists can be. His work anticipated the real-world blurring of the organic and the mechanical, the real and the virtual, that powered so much science fiction and so much horror over the last thirty years. The fact that horror and science fiction have become increasingly indistinguishable is partly due to Giger’s imagery, and designs that borrowed or outright stole from him.

When people asked Giger to describe the creatures he envisioned in his paintings in the early 70s—humanoid or sometimes outright monstrous beings that seemed at once organic and metallic, and that merged with each other and with their environments—he called them “biomechanoids.” The word “biomechanical” has become commonplace in writing about both science fiction and science, but Giger, a disciple of Salvador Dali, was plumbing the notion long before the rest of the world caught on. No, he was not the only artist doing this sort of hideously beautiful imagining: early works by David Cronenberg and David Lynch (both of whom Giger admired) also explored what might happen if the flesh as we know it were replaced by something else, or changed into something else. But Giger’s “Alien” designs brought the notion into mainstream thought, into the commercial marketplace, via a lavishly budgeted Hollywood feature and a lot of tie-in products, including that comic book I mentioned, and the action figures spawned by the original film, and all the toys and videogames that eventually tried to cash-in on the sequels, and all the other movies and TV series that pilfered aspects of Giger’s art: not just the extraterrestrial seductress in “Species,” which Giger helped design, but the creatures in the “Hellraiser” movies, and the Borg in the rebooted “Star Trek” shows and films—and, hell, almost anything in a modern sci-fi movie that’s supposed to be primally terrifying.

Giger perfected a particular way of seeing. He mainstreamed horrific yet tantalizingly sensuous imagery, a promise of assimilation and body perversion—a transformation of flesh into Not Flesh, or what Cronenberg called New Flesh.

There was a making-of book with production photos and sketches. I used to stare at that, too. My favorite image wasn’t any iteration of the alien. It was the so-called Space Jockey that the astronauts encounter when they’re exploring the wreck at the start of the movie.

I always wondered what his story was (and in Ridley Scott’s long delayed sorta-prequel “Prometheus,” we found out, and perhaps wished we hadn’t). I was intrigued by the way the Space Jockey’s body seemed to meld with the chair. Was he always bonded to that big gun, if in fact it was a gun and not, say, a telescope? Did the chair grow into him after he died? Or was it possible that the Space Jockey, the gun/telescope, the furnishings and the ship itself were all one organism?

We didn’t know. We had no way of knowing.

The not-knowing was the reason it stuck in our mind’s eye.

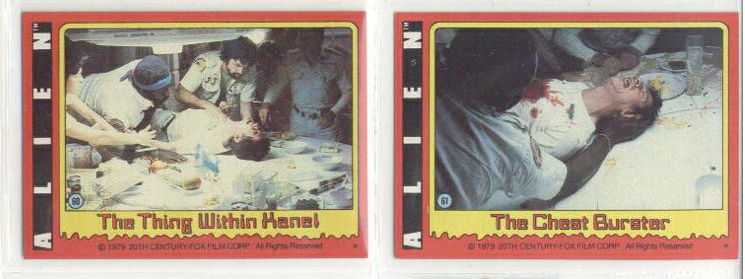

There were bubble gum cards based on “Alien,” you know. You could buy them in your local drugstore along with baseball cards and M&Ms. How many young artists’ own distinctive nightmare visions were emboldened by this utterly inappropriate product? How many of them look at Giger’s paintings today and smell bubblegum, and smile?

It never got old. We never got tired of looking at Giger’s xenomorph. Other filmmakers obsessed over it and put their own stamps on it. They never tired of picturing ways in which it might, say, lord over an egg chamber like a queen bee in her hive (“Aliens,” 1986) or invade and destroy a helpless dog (“Alien 3,” 1992) or swim through a flooded space station like a shark (“Alien Resurrection,” 1997). The creatures in “Independence Day” were unabashedly Giger-esque. The Predator in 1987’s “Predator” is basically a Giger xenomorph crossed with a Boba Fett-armored big game hunter; a Twentieth Century Fox studio boss once told me the original film in that series got a greenlight because somebody at Fox thought it would be cool to pit John Rambo against a Giger alien in a jungle. It was, and always will be, a classic movie monster, maybe the greatest of them all, and certainly a feat of imagination on par with Jack Pierce’s makeup in the Universal “Frankenstein” and the title creature of “E.T.” (which was designed and animated by Carlo Rambaldi, who did the animatronic versions of the xenomorph in the original film).

H.R. Giger is survived by creatures and films and fictional worlds that would not exist without his example, and by grateful dreamers to whom he gave splendid nightmares.