Filmmaker and history Arthur Dong has been fascinated by images of Chinese and Chinese-American people since he was a child growing up in San Francisco. His 2019 book Hollywood Chinese: The Chinese in American Feature Films is a lavishly illustrated, thoughtfully annotated volume that charts the changing images that he’s consumed over the decades and thinks about what they say and mean. The book is a belated companion of sorts to his similarly titled 2009 American Masters special. Dong is an Oscar-nominated and triple-Sundance winning documentary filmmaker whose work includes “Licensed to Kill,” “Family Fundamentals,” “Forbidden City, U.S.A.,” and “Coming Out Under Fire.”

On July 1, Dong will do a virtual book talk about Hollywood Chinese, sponsored by Friends of the American Chinese Museum, and moderated by veteran film producer Janet Yang (The Joy Luck Club, The People vs. Larry Flynt). This event is free, but registration is required. For information, click here.

What can you tell me about your childhood as a moviegoer, and how your tastes developed?

Ever since I can remember, I was taken to the movies by my parents. Now, we lived in Chinatown, San Francisco, and when I was much younger, when I was growing up—we’re talking about the 1950s and 1960s—there were five movie theaters in Chinatown. It was a small neighborhood, only a five or six block radius, and they all showed Chinese films, imports from Hong Kong. Those are the movies that I grew up with.

I’m bilingual. We spoke Chinese at home except with my siblings. We spoke English. With my parents, we spoke Chinese and I went to Chinese school, although I also went to English school as well, so I had both. So the movies I grew up with and knew since birth were Chinese movies. In terms of representation, my foundations were different stories and characters that were all Chinese, and they all looked like me, and they ran the gamut of representation.

As I got into my teen years, I started going to Hollywood films, and because particularly in San Francisco, there were a lot of repertory theaters at that time. We’re talking about the ‘60s now. They showed classic Hollywood films, so I started branching out my taste to Hollywood films. And also at that time, the 60s, TV was pretty much limited to the three big networks plus some local stations, but they always ran classic Hollywood films. I remember in the mornings, especially, that’s when I saw a lot of classic Hollywood films. I remember watching “Citizen Kane” in 1968 while I was watching the Chicago demonstrations at the Democratic Convention. Channel 7, ABC, ran the Apu Trilogy three weekends in a row, Sunday Night at the Movies. It’s crazy, right? So from childhood, having been brought up with a foundation of Chinese-language films and the full range of representation of characters that were played by Chinese, real Chinese, speaking Chinese on the screen, I grew up to also embrace Hollywood films, and with the help of TV and repertory theaters in San Francisco.

Was it kind of a reverse culture shock going from an early diet of Chinese cinema and then switching over to Hollywood, where there were so few people who looked like you?

I don’t remember a culture shock. I remember a thrill. The films that came out of Hong Kong, particularly in the ‘50s and ‘60s…the budgets were limited. It wasn’t bad, the industry in Hong Kong, but compared to Hollywood films, Hong Kong films were shot pretty quickly. They didn’t have the luxury of months of production time. And what you saw on screen, especially in costume dramas, the production design and the costume design was oftentimes pretty lacking. With the Chinese films, I would notice that the extras in the background always looked pretty bored, like they were dragged out of the streets and paid a pretty miniscule amount of money to be on the sets. They didn’t look very happy. Sometimes the sets looked like papier-mâché cutouts. But the story was the thing, and the excitement of seeing characters was the main event.

So the culture shock for me was about production value, particularly when I saw Hollywood films that were about the Chinese, like “The Mask of Fu Manchu” or “The Bitter Tea of General Yen.” Those are pretty well-designed films, very well-shot and well-lit. Even the costumes are excellent, especially the ones in “General Yen.” With the Hollywood movies, I remember saying “Wow! Look at that! A cast of thousands, and they really look involved! They really look engaged! They’re really into the scene!”

What about seeing white actors play Chinese people, under heavy makeup? How did that strike you?

[From “The Mask of Fu Manchu” ]

In terms of the yellowface casting, it was more of a curiosity. It didn’t strike me, at that time – and even now when I look at it and think about it – as offensive, but as a curiosity. This is what led me to try to explore this whole idea of casting representation in Hollywood films, to understand why those decisions were made and why they were acceptable.

As you’re telling me this I’m sitting here looking at the photograph opposite the table of contents, and it’s a publicity photo for “Charlie Chan in Shanghai” starring Warner Oland, who was Swedish, right?

He’s Swedish, yeah. I’ve seen writings here and there about the fact that he might have some Mongolian blood in him, so some people argue “Well, it wasn’t totally yellowface because he had some Mongolian blood!” Filmmakers did that kind of thing in all the Charlie Chan movies. I actually had thought they were kind of fun. I thought the kids in the film were hilarious, and they were all played by Chinese-Americans.

But as I started working in media, particularly producing Asian-American stories on film and being with other Asian-American media producers, I started hearing stories from people who didn’t grow up with Chinese representation on screen. They were hungering to see their own faces and their own stories on the screen, whether small or large, and they were offended by stuff like the Charlie Chan films. And I thought, “Whoa, that’s the point of view that I really needed to figure out.”

As we’re talking, I am looking at two-page spread from your book. On one side you have Carol Thurston having “yellowface” makeup applied for “China Sky.” On the facing page, the actress Maylia undergoes makeup for her screen debut in “To the Ends of the Earth.” The studio caption that originally accompanied that photo explained that she “…isn’t being made up as a Chinese girl, she is a Chinese girl, and a very charming one.’”

When I put this book together, before I even met the publisher, Angel City Press, I did the whole design on InDesign, the publishing tool. I learned how to use InDesign and I laid out the whole book, deciding what text would go with what picture and how the pictures would be laid out in conjunction with each other. And this page, which you’re pointing out, was laid out in my InDesign exactly the way it is in the book. I wanted the juxtaposition of these two photos in this one spread to show the situation that was happening in Hollywood at that time.

There have been a lot of press releases issued just in the last few weeks of television programs saying they will no longer cast against race for even voiceover parts. Allison Brie, who played an Asian-American character on “BoJack Horseman” expressed regret that she played the character all those years, and producers of “The Simpsons” put out a press release saying that from now on they’re not casting any more white actors as non-white characters. What do you think of all this?

I want to acknowledge the fact that the cinematic art has only been around for 100 years or so. Compared to other art forms, you can say it’s fairly new and still trying to figure itself out. At the beginning of film history, they weren’t thinking, really.

But it’s important to note here that it wasn’t like overnight the industry just suddenly opened its eyes and gone, “Oh no, we’ve made all these mistakes for all these past decades and all of this past century.” I can speak mostly for Asian-American history or Chinese-American history in Hollywood, but particularly with Chinese-American history: since the silent era, the Chinese-American community has spoken up and resisted and fought against stereotypes and demeaning characters. The Hollywood machine is big, the studio system is big, and it’s really hard to make change within that system.

I think these developments really coalesced in 2016. Remember at the Oscars in 2016 when Chris Rock was the host, and it was the second year of Oscars So White, which had started in 2015 but had resurrected itself because the nominees in the acting categories were Oscars So White again! Diversity and representation were really in the air. And so Chris Rock was hired, a black comedian and an actor, and everybody was excited about the show. When I say “everybody,” everybody that was interested in the issue of diversity and changing Hollywood. His opening monologue was beautiful, but then he told these really racist jokes about Asians as model minorities, and he said, “Now I want to introduce the Price-Waterhouse accountants,” which they often do on the Oscar show, and they come out with their briefcases to show how accurate and secretive they’re going to be in terms of the winners. And he brought out three Asian-American kids.

Yes, I remember this.

I served on the documentary branch of the Academy’s Board of Governors, and I’ve been a member of the Academy for over 20 years. I was sitting in my living room with my son, who is part-Asian. He was 12 years old. And I thought, “Oh my god. How am I going to talk about this? I really want to watch the show, but this is so egregious and so racist! And if he asks about that I need to stop watching the show and talk to him because I can’t ignore this.” But he really didn’t hear it, and I was kind of relieved that I was able to continue watching the show, but soon after that came Sacha Baron Cohen, who made a joke about “little yellow people and their little dongs.” Remember that?

Yes.

That just floored me, those two jokes in that year when the issue of diversity was so much in the forefront. A group of Asian Academy members got together and wrote a letter to the Academy to say how much we were against what happened and that we needed to see some fundamental changes. That was kind of the start of us telling Hollywood that this issue is not just black and white. The Academy leadership apologized and issued a formal apology.

I mention all of this to illustrate that these issues have been with us for a long time, and people have been working to counter them for long time. I’m on the inclusion advisory committee of the Academy’s museum. Because I’ve been so involved in writing and studying this book for my whole life, it’s really terrific to see some fundamental, concrete changes and decisions being made.

What do you think about the trend of removing racially or ethnically insensitive material from reruns of TV shows, editing offensive scenes out of movies, and so forth? I’m sitting here looking at a beautifully designed coffee table book which discusses a lot of films and images that I don’t think would even be allowed on screens now.

I just saw “Gone with the Wind” again a couple of weeks ago due to what happened with the film at HBOMax and frankly, I’d never particularly liked the film even when I first saw it on the big screen when it first got re-released. I remember watching it the first time and going, “What’s the big fuss?” But two weeks ago when I saw it again, I brought out the DVD and watched it again, and I was horrified. Even the intertitles, the text on screen that sets up the chapters of the story: I was reading them, and I was listening to the words of the characters, especially Leslie Howard as the “good guy,” and thinking,“this is like Trumpspeak.”

At the Academy Museum, one of our first meetings when we began the inclusion committee was about “The Birth of a Nation.” We had meetings and discussions about “How are we going to feature D.W. Griffith? Do we ignore it? Do we put it out?” And there was so much discussion about that particular film and that particular filmmaker, and then how to acknowledge that he was an important figure in the creation of the cinematic art, but then to look at his body of work and say “What kind of message was he sending out to the larger public?” Those discussions were the kind of discussions that are being had now about “Gone with the Wind.” I find it difficult to encourage and support showing those types of media productions without context.

Can we talk more about context? That seems like an important word to you.

A lot of that feeling about the importance of that word comes from having worked on the book. So many of the images in the book are egregious and offensive, but I needed to show them, and I think they should be seen, but with context.

That’s my attitude as well. I teach arts criticism. I deliberately include many selections from across the last century of arts writing that are taking what is, in retrospect, an offensive point of view about a certain movie, because I want to see what the students are going to say about it. That leads us into a discussion about the evolution of the art form and all the writing about the art form. It’s especially interesting when the writer of a piece drops in a word or phrase that is considered offensive now, but that nobody would’ve blinked at in 1987, or 1946, or whenever the piece was originally published.

That’s the lesson I learned watching “Gone with the Wind” again two weeks ago. It was like, “Whoa! I have so much more to learn.” Was I accepting these productions at face value, as “They are what they are”? I think it’s more complicated than that.

Well, I don’t “think” – it is more complicated than that.

I think of one of my favorite Mel Brooks lines: “Tragedy is when I cut my finger, and comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die.” Meaning we’re hypersensitive to every misfortune that befalls us, but we might laugh off things that are a thousand times worse for somebody else.

That’s very on-point with that Sacha Baron Cohen joke. That was pretty out there, that joke. I’m not sure he can even say he was just tone deaf and didn’t know what he was doing.

A few years ago I was told by a person with hearing problems that “tone-deaf” is considered a slur. I was taken aback. I’d been using it my entire life.

That’s interesting. Tell me about that.

Abled people use words having to do with disability that indicate disapproval or condemnation, like saying something is “lame” or “tone-deaf” or that if a movie didn’t succeed because of something it did poorly that it was “Crippled by its bad editing.” These are words and phrases I’ve been using my entire life, and now I know they’re offensive so I try to catch myself before using them. But it’s an ongoing process because there’s a lot of wiring to unplug here.

Yeah, and it’s no wonder that there are certain parts of our population that are finally saying “Enough is enough.” There’s a part of the population that uses the term “politically correct” in a derogatory way. A certain voting bloc says, “We want to go back to what things were. We don’t want our lives to be complicated by whether or not we can use the term ‘tone-deaf’ or whether we can use the word ‘crippled’ in the way you describe.” I never thought of that. You’re absolutely correct.

I think we’re witnessing a restructuring of our educational process and our imaginations, which is good. But it’s going to take a lot of work.

So to be clear, you’re not saying, “Remove these offensive things from public view?” You’re saying “Hang labels on them and contextualize them”?

I’m saying show them as lessons. Show them as examples of a certain mindset, and what kinds of thoughts or motives or creative processes went through minds of the creators, and really dig into why these portrayals or stories were told as they were. I think there are lessons to be learned.

In my film “Hollywood Chinese,” I interview Christopher Lee about Fu Manchu and Turhan Bey about his role in “Dragon Seed,” and Luise Rainer, who played a Chinese peasant worker in “The Good Earth.” I wanted to do that because I wanted to understand what it was they were thinking and what they thought now. It was the same as in my film “Licensed to Kill,” about the killers of gay men. I didn’t interview victims for that film. I only interviewed killers of gay men for that film, because I wanted to ask, “Why did they do it?” That was the kickoff for the entire investigation. I’ve always believed that to fix a problem you need to really understand who’s causing the problem, or what is causing the problem because without understanding the root of the problem, how can we really fix it?

Can you give me an example of this philosophy from the book?

There’s an article in the book from the magazine American Cinematographer, written by Cecil Holland, the makeup guy who did “Mask of Fu Manchu” and “The Good Earth.” I printed the whole first page of the article, that’s the way I laid it out, and I said to the publisher and the designer, “I want to give this a whole page,” the first page of the article. Cecil Holland writes, in a very glorious way, about the work that he’s done to create makeup for Boris Karloff to become Fu Manchu. He was writing it from an artistic point of view, a creators’ point of view, but the language he’s using is racist and the attitudes he points out are racist.

As a creator myself, I needed to understand that. I needed to understand where his mindset was and how he thought that what he was doing was not racist, and what he was doing as an artist. This is a conversation I’ve brought up several times in our meetings at the museum, dealing with the makeup display. The reaction was really critical of the makeup used for blackface or yellowface, and there were certain makeups created by Max Factor to transform a white actor to be a brown, yellow, or black person. I agree that we needed to be critical of these practices.

But at the same time, just looking at it from a makeup person’s point of view, they were being artists. Their job was, as a makeup artist, “How do I create makeup that will work onscreen?” That’s the two sides to the coin that I’m interested in looking at, and the Cecil Holland article in the book really points out how, when we look at it today, we might think, “How racist,” but wait a minute: look at it as an artist. Because that’s how he was approaching the assignment.

I had a friend, who is white, who went to India and immediately got cast in a TV series where he played a sadistic British officer, because they just thought his face had “the right look.” It gave him a very small taste of what it must have felt like to be a black actor with dark skin in 1975 or something, where if you got cast in a Hollywood movie, there was a high likelihood that you were playing a mugger.

Thinking about the example of your friend: if you look at Chinese movies—not all of them, but some of them—they have the most racist white characters! It’s like, it’s across cultures, this misunderstanding or misrepresentation of “the other,” but it’s not just white people. I know in Chinese movies the white characters are always idiots! I mean, I laugh when I watch them because it’s like, “Oh good, some comeuppance, right?” I laugh because it’s funny. But then I also realize, “Oh my god, we’re just as guilty of doing the same thing we’re angry about!” I know I have stereotypes about other groups of people and I catch myself, but I don’t always do that. When I do I go “Whoa! Where’d that come from?”

I wanted to ask you about the parts of your book that deal with films about the Tong Wars. I didn’t know that these stories were being told as early as 1919-1920. That’s as rich a subcategory of cinema as Italian mafia films.

Yeah, that could be, and it still carries on today. We still see remnants of what was happening in the early 1900s, particularly in TV shows when you have the NYPD or LAPD shows, or even in other cities. The Chinese mafia, or hoodlums, or Tong Wars, those characters are still around. Sometimes I get immune to it and I’m like, “Oh yeah,” and I have actor friends in the business who say, “Yeah, we still have to do those roles, because if we don’t, we can’t make a living.”

Do you think there’s an element, as there is among some Italian-Americans, that takes pride in some of these representations, because they’re tough, charismatic, intimidating characters who are the stars of the movie?

Well, so far I haven’t heard any complimentary remarks about Tong Wars movies, drug dealers from Hong Kong and the Chinese mafia. But I think what you’re referencing relates to the myth of Bruce Lee. Lee fashioned himself into a mythic character, and part of that is based on his brutal strength and his ability to ward off his attackers physically. It’s based on violence. He was a very smart man and he was very philosophical. But what really sells that his strength, his brute strength and his mastery of Kung Fu, his ability to beat up the big guys who were oftentimes larger than him.

Part of me really appreciates that because it breaks the stereotype of the emasculated Asian male, or the eunuch, but at the same time, it’s based on brute strength only oftentimes. That doesn’t always sit well with me. That has become a stereotype as well.

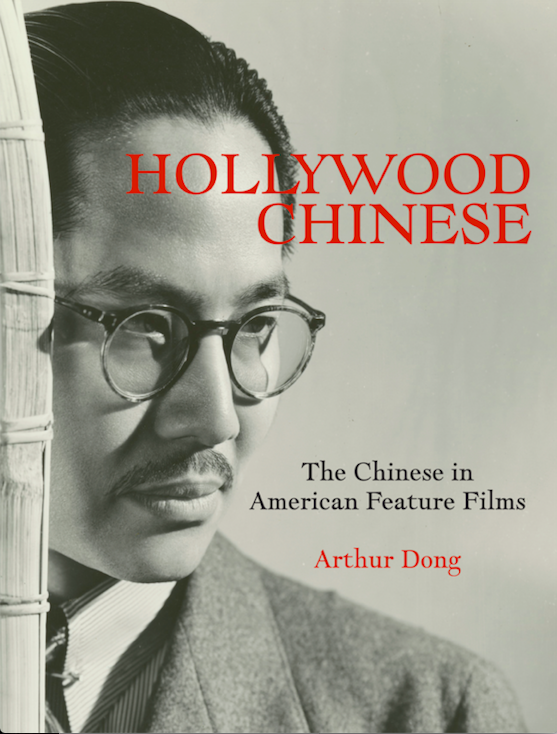

I just noticed something, and I wanted to ask you about it: the cover image of this book is of Keye Luke in “Burma Convoy.” You reproduce the same picture on the inside and he’s holding a gun. You cropped the gun out of the cover image. Why?

You want to talk about that?

Yeah, please, it’s interesting.

I think you’re the first person that brought it up. You’re the only one who’s asked me about it so far. That’s great! I was waiting for someone to bring this up! [Laughs]

Well, for starters, it’s a beautiful image, cropped or uncropped, but it wasn’t my first choice for the cover because of the gun. I said for me, the gun just glorifies and perpetuates gun violence. I understand that that really is a noir film, in terms of composition it has a great aesthetic, it’s a great photograph. But I argued against it because it’s my book, OK?

I ask about it because when I looked at the cover, not having seen the movie that the image comes from, I imagined a whole other movie out of his expression. Only knowing Keye Luke from when he was a much older character actor, I thought, “Wow, who is that good looking guy, and what romantic drama is this from?” He looks like the second male lead who doesn’t get the girl, and he’s got glasses and a suit. I imagined that he’s looking at the woman he wants to be with, who is unfortunately with with the other guy who’s actually the star of the movie. And yet he’s a beautiful man in and of himself. He looks like he could be in a Wong Kar-wai film or something.

And then I look at the uncropped image inside of the book, and I go, “Oh, I see, he’s got a gun. It’s a gangster picture.” But as soon as you remove the gun from the photo it never even occurs to me that this guy could be a criminal. It’s more like, “Oh, this must be from a romantic film.”

You are thinking exactly what I thought. After the publisher agreed that they wouldn’t put this image with the gun on the cover, we went looking for other images, but we always came back to this. Finally, someone said “What if just we cut out the gun?” And then the designer did it, and I had exactly the reaction you had. I said, “What a handsome man! What a beautiful hunk!” [Laughs] It’s like, because of that gun I couldn’t see the photograph. All I saw was the gun.

I hope you don’t feel like I’m overdoing it talking about this one image so much, but I feel like this one editorial decision is the book, in a way.

Yeah, definitely. That was my point to the publisher. That’s when I said, “This is my book. I cannot have that gun represent my book forever and ever.” Without the gun he’s a handsome man, a leading man, and the image is full of mystery. What is he looking at? What is he thinking? Is he in love? What’s his story? What is it?