NEW YORK — Woody Allen was filming his new movie down around the corner of Broadway and 19th Street the other day, and he was under a certain amount of pressure. One of his stars, Mia Farrow, was pregnant and was playing a pregnant woman, and now the doctor was speculating that she might deliver before she was finished with the role. His editor, Sandy Morse, was also pregnant, and might deliver at any moment.

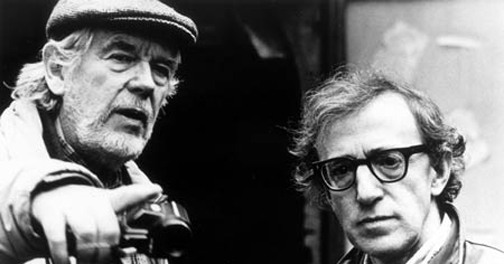

Allen was filming seven days a week to beat those deadlines on this movie which, like all of his movies, has no title and is being filmed in secrecy. He was also planning to spend his lunch break talking about “September,” his latest film, which opens around the country in December and is not a comedy and it up against a lot of big-budget movies which are comedies, and so it was with a certain irony that he was reminded of his situation by Sven Nykvist, who is the cinematographer on the current production.

All Nykvist really said, on his way to his own lunch, was hello. But that was enough to start Woody Allen thinking about his hero Ingmar Bergman, the great Swedish director who employed Nykvist to film many of his masterpieces.

“I was going to visit Bergman last year when we were all in Sweden,” Allen said, settling into the front seat of the car which would take us to lunch, “but I thought, you know, with all of Mia’s kids, getting all the right travel documents and getting seats on the flights to Faro, the island where he lives, was just too much of an undertaking. I did meet him once. Do you know how he spends his day, now that he’s in retirement? He wakes up early in the morning, he sits quietly for a time and listens to the ocean, he has breakfast, he works, he has an early lunch, he screens a different movie for himself each and every day, he has an early dinner, and then he reads the newspaper, which would be too depressing for him to read in the morning.”

As Allen described Bergman’s idyll, the car shot down Broadway and went weaving through traffic to bring us up with a half before John’s Pizza, the celebrated Greenwich Village pizzeria.

“I eat here whenever I have the nerve to have a good meal,” he explained. In the back room, the manager came to take his order and said they had laid in a supply of a special low-fat cheese Allen prefers on his pizza. Allen ordered a medium cheese. So did I. The manager suggested we could share a large, and we both simultaneously said, no, we’d have the two mediums. You’ve got to know someone pretty well to share a pizza with them. It’s like a toothbrush. It’s not for interview situations.

Allen was looking just a slight bit harried and rushed, as a director has a right to when he is making a film, even if he is not, at 51, awaiting the birth of his first baby, as Allen is.

“The thing I really feel about that is very complicated,” he said. “You know, Mia and I adopted a baby, Dylan, before she got pregnant. And for me the child we are having together is not my first child, but my second, because there is absolutely no difference in the love I would feel for the child we’re having together, and the love I feel for Dylan. In fact, I love Dylan so much that I would be pleasantly surprised if I love this baby as much as the one we have adopted.

“I’ve noticed in recent months that I lot of the people I know are having babies. And women friends will say they want to get pregnant, the biological clock is ticking, and I tell them not to bother to get pregnant–just adopt. When I first met Mia and she was telling me about all the children. I said, what a nice gesture. And she said, no, I had it all wrong, it’s not what she had done for them, it was what they had done for her. Now I know what she meant.”

The waiter arrived with our pizza. “Hey, you know,” he said, “what a coincidence. I was watching cable TV last night, and one of your movies was on, you know, the one you did with Mary Hartman…”

“Right, Louise Lasser,” Allen said.

“…and I was saying to my son’s fiancee, wouldn’t it be a coincidence if he came in today, and here you are.”

“Well, it’s great pizza,” Allen said. He took a slice and doubled it up lengthwise and started to eat it. John’s Pizza is owned by a man named Pete Castellotti, who has had roles in three of Allen’s movies, “Broadway Danny Rose,” “The Purple Rose of Cairo,” and “Radio Days.” The pizzeria is an illustration of Allen’s whole approach to Manhattan, an island which he loves so much that he once spent the Fourth of July watching “Poltergeist” in a midtown movie palace, just to avoid the terrible experience of having to spend the holiday in the country.

That is why the plot of “September,” the new Allen film, is some distance from his usual stories. The film takes place in an isolated country cottage where several romances are running their separate courses, fairly swiftly. Elaine Stritch plays a legendary, much-married actress of a certain age, now wed to Jack Weston, a wealthy manufacturer. Mia Farrow plays her daughter, whose life has never been the same since a day in adolescence when she seized a gun and killed her mother’s gangster lover. Some months before the story begins, Farrow came out to the country to recover from a nervous breakdown, and took many long walks with a neighbor, Denholm Elliott, who is now quietly and hopelessly in love with her.

But Farrow is in love with a writer who lives nearby. The writer, however, is just in the process of falling in love with Dianne Weist, Farrow’s best friend, who has left her husband and is spending some time in the country to sort out her thoughts. Weist does not want to hurt Farrow’s feelings, but feels swept away by passion and feels this thing may be bigger than either of them. During a long weekend in the country, all of these entanglements sort themselves out, with much pain and some truth and a good deal of Allen’s literate, ironic dialog.

“This story has a very old provenance,” Allen explained in the back room of the pizzeria. “You know Mia has this country house, a real Chekovian setting, a little cottage, a little lake, very Russian. For a long time I’ve wanted to write a little Russian family drama to set there. I finally did it, but by the time the screenplay was ready the weather had changed, and so we had to built the sets in Astoria Studios here in New York.”

“Therefore avoiding the need to go out to the country,” I observed.

“I’m actually sort of glad it turned out that way,” Allen said. “I knew I wanted to do this movie, but I kept asking myself if I could stay in the country for six weeks, where every 15 minutes seems like six hours. I knew I would be working all the time, surrounded by friends and associates, and yet still I’d miss the city. Although let me tell you, shooting at Astoria is not all that easy. You ever been out there? My idea of a perfect location for a studio would be on Park Avenue, right where the Armory is.

“‘Hannah and Her Sisters,’ that was the perfect set-up. We shot a lot of it in Mia’s apartment, and all I had to do was cross Central Park every day. Bergman shoots right in his own house, and on his island. I’d shoot in my house, but I live in a co-op apartment, and it’s against the rules. I keep thinking, maybe if I had a beach house, I could maybe go out there and shoot…”

“But you had a beach house,” I said. “You had a beach house, and you never went to it. That’s what you told me once.”

He folded another piece of pizza and regarded it as if it were a beach house.

“I really bought it for my sister. I went out and looked at it, and bought it, and I thought, gee, this is nice, maybe I could use it for myself some weekends, you know. But I only went out once. I hated it, and my sister hated it, and we sold it.”

He performed that characteristic Woody Allen shrug, the one with the quizzical expression that seems to say, you just can’t depend on beach houses anymore.

“Shooting in Mia’s house led to a very strange experience for Mia the other night,” he said. “She told me she was in bed in her bedroom, looking at “Hannah and Her Sisters‘ on the TV set at the end of the bed. She realized she was looking at a scene in the movie that showed the same bed and the same TV set, in the same room. “

I said I had been meaning to ask him about “King Lear,” the Jean-Luc Godard film he agreed to appear in. That was the movie inspired by the famous deal at the Cannes Film Festival three years ago, when Godard and Cannon president Menachem Golan signed a deal on a table napkin. I told Woody I had seen the napkin, on which Golan misspelled Godard’s name, but promised him a script by Norman Mailer, and a cast including Orson Welles as Lear and Woody Allen as the Fool.

“Norman Mailer wrote the screenplay?” Allen asked.

“Yeah.”

“Well, there was no screenplay at all the day Godard shot me. I worked for half a day. I completely put myself into his hands. He shot over in the Brill Building, working very sparsely, just Godard and a cameraman, and he asked me to do foolish things, which I did because it was Godard. It was one of the most foolish experiences I’ve ever had. I’d be amazed if I was anything but consummately insipid.

“He was very elusive about the subject of the film. First he said it was going to be about a Lear jet that crashes on an island. Then he said he wanted to interview everyone who had done King Lear, from Kurosawa to the Royal Shakespeare. Then he said I could say whatever I wanted to say. He plays the French intellectual very well, with the 5 o’clock shadow and a certain vagueness. Meanwhile, when I got there for the shoot, he was wearing pajamas — tops and bottoms — and a bathrobe and slippers, and smoking a big cigar. I had the uncanny feeling that I was being directed by Rufus T. Firefly — you know, when Groucho is supposed be the great genius, and nobody has the nerve to challenge him? But Godard is supposed to be a genius, I guess…”

He looked uncertain. I asked him about the campaign against colorization, the insidious and immoral practice of taking old black and white films and artificially adding color to them. Allen journeyed to Washington in August to testify at Senate hearings on the question.

“I’m telling you,” he said, sounding dubious, “we may not win this fight. It’s amazing how insensitive people are on the issue. Even well-meaning newspaper editorials, like one the other day in the Atlanta Constitution, completely miss the point. They treat it as a free enterprise issue, instead of asking whether anyone has the right to change someone else’s work. And when you go to Washington and see what’s there… I dunno. Most of the senators and congressmen were okay, but some of them were real backwoodsmen. Listening to them at the hearings was like sitting on an airplane trapped next to a guy from the swamps. They kept asking a million questions and never grasped the real issues. One guy asked me if I would be against colorizing ‘Gone With the Wind.’ He didn’t know it was made in color.”

“Have you ever thought about making a political satire?”

“I’ve thought a lot about it. Especially now. When Reagan was elected, I knew he was gonna be bad, but I didn’t realize how bad. They say we get the President we deserve. Great, but I got the President they deserved.”

The pizza was mostly gone, and it was time for Allen to get back in his car and return to the set. On the way back, winding through the busy streets, he fell to musing on great movie directors.

“Bergman has apparently definitely retired,” he said. “No more Bergman films. Bunuel is dead. Truffaut. You didn’t like the new Fellini movie? I haven’t seen it yet. Jeez, there are so few of the giants left, that when one of them like Fellini makes a movie, you can’t wait to see it. But that whole generation is disappearing. No more giants.”

“What about American directors?” I asked him.

“Isn’t that funny?” he said. “I never even think of the Americans as geniuses. We had one. Orson Welles. Gone too.”